8.3 Psychological Needs as Motivators

KEY THEME

According to the motivation theories of Maslow and of Deci and Ryan, psychological needs must be fulfilled for optimal human functioning.

KEY QUESTIONS

How does Maslow’s hierarchy of needs explain human motivation?

What are some important criticisms of Maslow’s theory?

What are the basic premises of self-determination theory?

Why did you enroll in college? What motivates you to study long hours for an important exam? To push yourself to achieve a new “personal best” at a favorite sport? Rather than being motivated by a biological need or drive like hunger, such behaviors are more likely motivated by the urge to satisfy psychological needs.

In this section, we’ll first consider two theories that attempt to explain psychological motivation: Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs and the more recently developed self-determination theory of Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

A major turning point in the discussion of human needs occurred when humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow developed his model of human motivation in the 1940s and 1950s. Maslow acknowledged the importance of biological needs as motivators. But once basic biological needs are satisfied, he believed, “higher” psychological needs emerge to motivate human behavior.

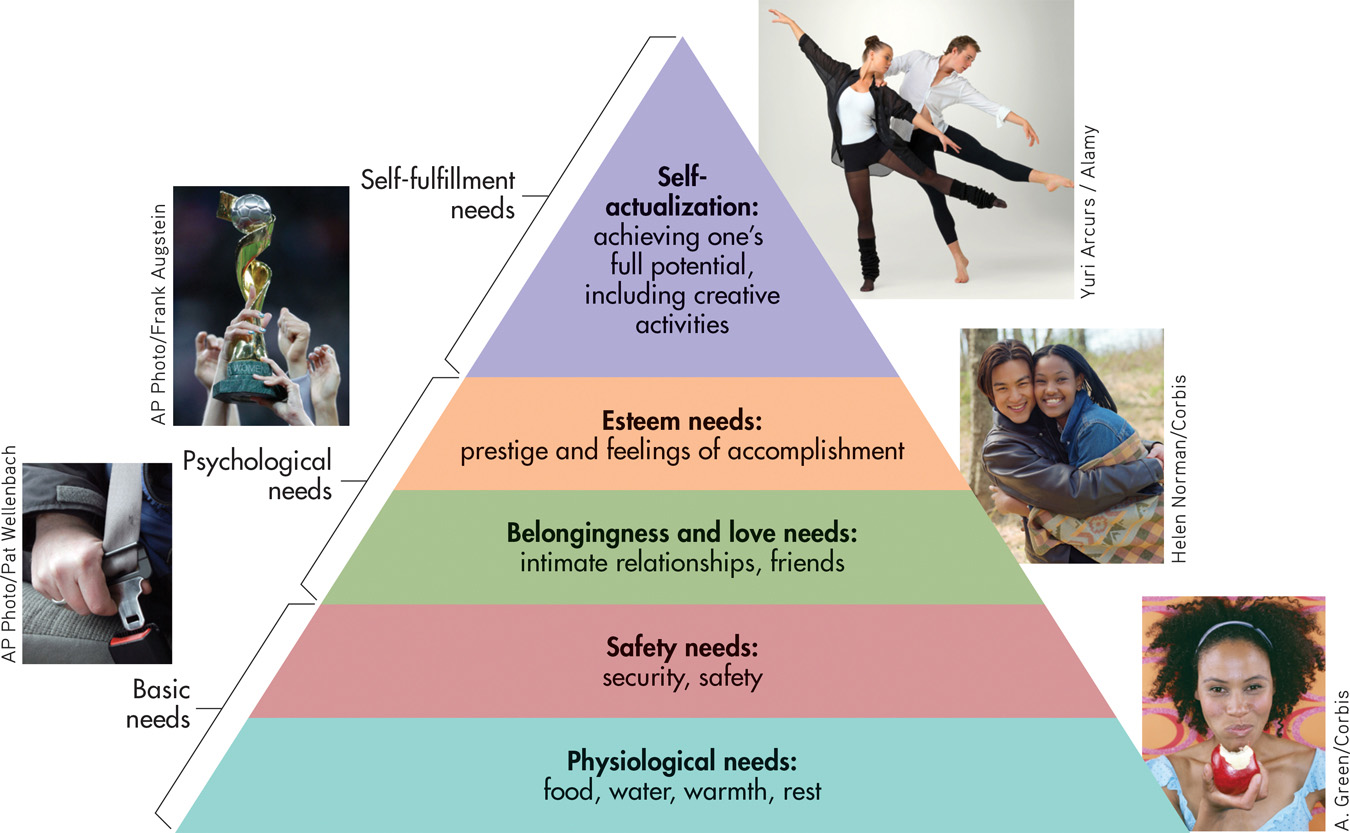

The centerpiece of Maslow’s (1954, 1968) model of motivation was his famous hierarchy of needs, summarized in FIGURE 8.3. Maslow believed that people are motivated to satisfy the needs at each level of the hierarchy before moving up to the next level. As people progressively move up the hierarchy, they are ultimately motivated by the desire to achieve self-actualization. The lowest levels of Maslow’s hierarchy emphasize fundamental biological and safety needs. At the higher levels, the needs become more social and psychologically growth-oriented, culminating in the need to achieve self-actualization.

hierarchy of needs

Maslow’s hierarchical division of motivation into levels that progress from basic physical needs to psychological needs to self-fulfillment needs.

What exactly is self-actualization? Maslow (1970) himself had trouble defining the term, saying that self-actualization is “a difficult syndrome to describe accurately.” Nonetheless, Maslow defined self-actualization in the following way:

It may be loosely described as the full use and exploitation of talents, capacities, potentialities, etc. Such people seem to be fulfilling themselves and to be doing the best that they are capable of doing…. They are people who have developed or are developing to the full stature of which they are capable.

self-actualization

Defined by Maslow as a person’s “full use and exploitation of talents, capacities, and potentialities.”

Maslow identified several characteristics of self-actualized people, which are summarized in TABLE 8.2.

Maslow’s Characteristics of Self-Actualized People

| Realism and acceptance | Self-actualized people have accurate perceptions of themselves, others, and external reality. |

| Spontaneity | Self-actualized people are spontaneous, natural, and open in their behavior and thoughts. However, they can easily conform to conventional rules and expectations when necessary. |

| Problem centering | Self-actualized people focus on problems outside themselves. They often dedicate themselves to a larger purpose in life. |

| Autonomy | Although they accept and enjoy other people, self-actualized individuals have a strong need for privacy and independence. |

| Continued freshness of appreciation | Self-actualized people continue to appreciate the simple pleasures of life with awe and wonder. |

| Peak experiences | Self-actualized people commonly have peak experiences, or moments of intense ecstasy, wonder, and awe during which their sense of self is lost or transcended. |

| Source: Research from Maslow (1970). | |

Maslow’s model of motivation generated considerable research, especially during the 1970s and 1980s. Some researchers found support for Maslow’s ideas (see Graham & Balloun, 1973). Others, however, criticized his model on several points (see Fox, 1982; Neher, 1991; Wahba & Bridwell, 1976).

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

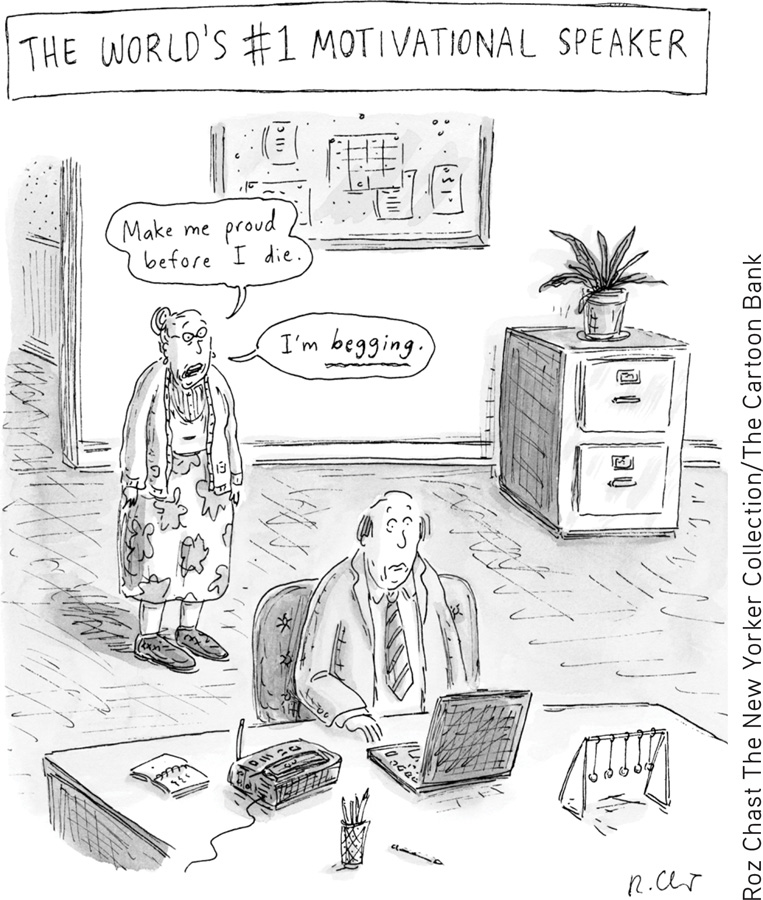

Is it true that people need to satisfy basic needs before they can try to achieve higher needs, like artistic expression?

First, Maslow’s notion that we must satisfy needs at one level before moving to the next level has not been supported by empirical research (Sheldon & others, 2001). Second, Maslow’s concept of self-actualization is very vague and almost impossible to define in a way that would allow it to be tested scientifically. And, Maslow’s initial studies on self-actualization were based on limited samples with questionable reliability. For example, Maslow (1970) often relied on the life stories of acquaintances whose identities were never revealed. He also studied the biographies and autobiographies of famous historical figures he believed had achieved self-actualization, such as Eleanor Roosevelt, Abraham Lincoln, and Albert Einstein.

There is a more important criticism. Despite the claim that self-actualization is an inborn motivational goal toward which all people supposedly strive, most people do not experience or achieve self-actualization. Maslow (1970) himself wrote that self-actualization “can seem like a miracle, so improbable an event as to be awe-inspiring.” Maslow explained this basic contradiction in a number of different ways. For instance, he suggested that few people experience the supportive environment that is required to achieve self-actualization.

Perhaps Maslow’s most important contribution was to encourage psychology to focus on the motivation and development of psychologically healthy people (King, 2008). In advocating that idea, he helped focus attention on psychological needs as motivators.

Question 8.12

2tJ9OFos0t1EHhdjuf3W0PExrwpA+jDCnBBcGHtzxQoRAR9j9Xge+603riItpidcBGcLngYREiFoRy51gwPXDFzGjiqv0p6Bys4KXBrR2aaovoHLnHWFbrkslu6P1i3jP8L8QEVQopYNLWo+wjorU6fnJfIhrzwGVvJ9vHc4HDVEwCWYtZwFFxdODaDPaxYWK7nqunHO9Xwpcm9QvWGNEyD6yltu9KMxnJWQcAXRubP8UHiezUtsVDTQkexgLOItkpHvGyjM45LNLuiCo9LvTg==Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory, abbreviated SDT, is a contemporary theory of motivation developed by University of Rochester psychologists Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan (2000, 2012a, b). Much like Maslow’s theory, SDT’s premise is that people are actively growth oriented and that they move toward a unified sense of self and integration with others. To realize optimal psychological functioning and growth throughout the lifespan, Ryan and Deci contend that three innate and universal psychological needs must be satisfied:

Autonomy—the need to determine, control, and organize one’s own behavior and goals so that they are in harmony with one’s own interests and values.

Competence—the need to learn and master appropriately challenging tasks.

Relatedness—the need to feel attached to others and experience a sense of belongingness, security, and intimacy.

self-determination theory (SDT)

Deci and Ryan’s theory that optimal human functioning can occur only if the psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied.

Like Maslow, Deci and Ryan view the need for social relationships as a fundamental psychological motive. The benefits of having strong, positive social relationships are well documented (Leary & Allen, 2011). Another well-established psychological need is having a sense of competence or mastery (Bandura, 1997; White, 1959).

One subtle difference in Maslow’s views compared to those of Deci and Ryan has to do with the definition of autonomy. Deci and Ryan’s definition of autonomy emphasizes the need to feel that your activities are self-chosen and self-endorsed (Ryan & Deci, 2011; Niemiec & others, 2010). This reflects the importance of self-determination in Deci and Ryan’s theory. In contrast, Maslow’s view of autonomy stressed the need to feel independent and focused on your own potential (see TABLE 8.2 on the previous page).

How does a person satisfy the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness? In a supportive social, psychological, and physical environment, an individual will pursue interests, goals, and relationships that tend to satisfy these psychological needs. In turn, this enhances the person’s psychological growth and intrinsic motivation (Sheldon & Ryan, 2011). Intrinsic motivation is the desire to engage in tasks that the person finds inherently satisfying and enjoyable, novel, or optimally challenging. The doctors, nurses, and other volunteers who traveled to Nepal in the Prologue story displayed intrinsic motivation, taking time away from work and family to contribute their efforts to helping others in a distant land.

intrinsic motivation

The desire to engage in tasks that are inherently satisfying and enjoyable, novel, or optimally challenging; the desire to do something for its own sake.

In contrast, extrinsic motivation consists of external influences on behavior, such as rewards, social evaluations, rules, and responsibilities. Of course, much of our behavior in daily life is driven by extrinsic motivation (Ryan & La Guardia, 2000). According to SDT, the person who has satisfied the needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness actively internalizes and integrates different external motivators as part of his or her identity and values (Ryan & Deci, 2012). In effect, the person incorporates societal expectations, rules, and regulations as values or rules that he or she personally endorses.

extrinsic motivation

External factors or influences on behavior, such as rewards, consequences, or social expectations.

What if one or more of the psychological needs are thwarted by an unfavorable environment, one that is overly challenging, controlling, rejecting, punishing, or even abusive? According to SDT, the person may compensate with substitute needs, defensive behaviors, or maladaptive behaviors. For example, if someone is frustrated in satisfying the need for relatedness, he or she may compensate by chronically seeking the approval of others or by pursuing substitute goals, such as accumulating money or material possessions.

In support of self-determination theory, Deci and Ryan have compiled an impressive array of studies, including cross-cultural studies (Deci & Ryan, 2000, 2012a, b). Taking the evolutionary perspective, they also argue that the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness have adaptive advantages. For example, the need for relatedness promotes resource sharing, mutual protection, and the division of work, increasing the likelihood that both the individual and the group will survive.

Question 8.13

bEluYK129i1+6xYxFsAOUXG92bKGywLJWO788lXhZ2+9MV90r8p08H7DZKxuqwInZE6B/Z9KMLN0Bj9izaXvcx32y4yLHYCF6oJWcg+TuHxnjfq6upJwMTsjHDUmx6eh7a3YWnHcOfFqis0pHYHvxDodE8vfUhutSwRj/6BQmLOdG7jkwhuCXFdihHMykZ0yuvaEKkevILK61aDjEtzEt2WdDlLufSVaoEoTSXf1OAY02cA52vpJqqb4d1ilgk3fDsUabXoTvRMbbahYCompetence and Achievement Motivation

KEY THEME

Competence and achievement motivation are important psychological motives.

KEY QUESTIONS

How does competence motivation differ from achievement motivation, and how is achievement motivation measured?

What characteristics are associated with a high level of achievement motivation, and how does culture affect achievement motivation?

In self-determination theory, Deci and Ryan identified competence as a universal motive. You are displaying competence motivation when you strive to use your cognitive, social, and behavioral skills to be capable and exercise control in a situation (White, 1959). Competence motivation provides much of the motivational “push” to prove to yourself that you can successfully tackle new challenges, such as striving to do well in this class or making it to the top of a steep trail.

competence motivation

The desire to direct your behavior toward demonstrating competence and exercising control in a situation.

A step beyond competence motivation is achievement motivation—the drive to excel, succeed, or outperform others at some task. For example, in the chapter Prologue, Pasang clearly displayed a high level of achievement motivation. Climbing Everest and becoming an internationally certified mountaineering guide are just two examples of Pasang’s drive to achieve. In fact, in late July, 2014, Pasang summited K-2, the second-highest and, some say, most dangerous mountain in the world. Pasang and her two Nepali teammates were the first all-female team to successfully conquer K-2. Their mission’s avowed purpose was to bring attention to the importance of climate change and to encourage sustainable development in the Himalayas.

achievement motivation

The desire to direct your behavior toward excelling, succeeding, or outperforming others at some task.

For more on the historic climb by Pasang and her teammates, visit: http:/

In the 1930s, Henry Murray identified 20 fundamental human needs or motives, including achievement motivation. Murray (1938) defined the “need to achieve” as the tendency “to overcome obstacles, to exercise power, [and] to strive to do something difficult as well and as quickly as possible.” Also in the 1930s, Christiana Morgan and Henry Murray (1935) developed a test to measure human motives called the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT). The TAT consists of a series of ambiguous pictures. The person being tested is asked to make up a story about each picture, and the story is then coded for different motivational themes, including achievement. In Chapter 11, on personality, we’ll look at the TAT in more detail.

Thematic Apperception Test (TAT)

A projective personality test, developed by Henry Murray and colleagues, that involves creating stories about ambiguous scenes.

In the 1950s, David McClelland, John Atkinson, and their colleagues (1953) developed a specific TAT scoring system to measure the need for achievement, often abbreviated nAch. Other researchers developed questionnaire measures of achievement motivation (Spangler, 1992; Ziegler & others, 2010).

Over the next four decades, McClelland and his associates investigated many different aspects of achievement motivation, especially its application in work settings. In cross-cultural studies, McClelland explored how differences in achievement motivation at the national level have influenced economic development (McClelland, 1961, 1976; McClelland & Winter, 1971). He also studied organizational leadership and power motivation—the urge to control or influence the behavior of other people or groups (McClelland, 1975, 1989).

Hundreds of studies have shown that measures of achievement motivation generally correlate well with various areas of success, such as school grades, job performance, and worker output (Senko & others, 2008). This is understandable, since people who score high in achievement motivation expend their greatest efforts when faced with moderately challenging tasks. In striving to achieve the task, they often choose to work long hours and have the capacity to delay gratification and focus on the goal. They also tend to display original thinking, seek expert advice, and value feedback about their performance (McClelland, 1985b).

ACHIEVEMENT MOTIVATION AND CULTURE

When it is broadly defined as “the desire for excellence,” achievement motivation is found in many, if not all, cultures. In individualistic cultures, like those that characterize North American and European countries, the need to achieve emphasizes personal, individual success rather than the success of the group. In these cultures, achievement motivation is also closely linked with succeeding in competitive tasks (Markus & others, 2006; Morling & Kitayama, 2008).

In collectivistic cultures, like those of many Asian countries, achievement motivation tends to have a different focus. Instead of being oriented toward the individual, achievement orientation is more socially oriented (Bond, 1986; Kitayama & Park, 2007). For example, students in China felt that it was unacceptable to express pride for personal achievements but that it was acceptable to feel proud of achievements that benefited others (Stipek, 1998). The person strives to achieve not to promote himself or herself but to promote the status or well-being of other members of the relevant social group, such as family members (Matsumoto & Juang, 2008).

Individuals in collectivistic cultures may persevere or aspire to do well in order to fulfill the expectations of family members and to fit into the larger group. For example, the Japanese student who strives to do well academically is typically not motivated by the desire for personal recognition. Rather, the student’s behavior is more likely to be motivated by the desire to enhance the social standing of his or her family by gaining admission to a top university (Kitayama & Park, 2007).

CONCEPT REVIEW 8.2

Psychological Needs as Motivators

Select the correct answer.

1. Compared to those in individualistic cultures, people in collectivistic cultures:

| A. | are much less likely to achieve self-actualization |

| B. | are more likely to value extrinsic motivation over intrinsic motivation |

| C. | are more likely to be motivated to pursue achievements to promote the social status of their family or social group |

| D. | place much less value on the importance of self-esteem in psychological well-being |

2. Who said, “[It] can seem like a miracle, so improbable an event as to be awe-inspiring,” and what was he or she describing?

| A. | Edward Deci, describing intrinsic motivation |

| B. | Abraham Maslow, describing self-actualization |

| C. | Henry Murray, describing the development of the Thematic Apperception Test |

| D. | Julia Roberts, describing how difficult it is to achieve stardom in Hollywood |

3. Deci and Ryan’s self-determination theory:

| A. | accurately describes psychological motives in individualistic but not collectivistic cultures |

| B. | has shown that self-actualization can be achieved even if only one of the innate psychological needs has been satisfied |

| C. | challenged the evolutionary perspective’s notion that the need for relatedness has adaptive advantages |

| D. | contends that psychologically healthy people internalize external motivators as part of their identity and values |

4. People who rate high on achievement motivation:

| A. | have the capacity to delay gratification in working hard to achieve goals |

| B. | explain their failures as being due to a lack of effort or abilities |

| C. | are no more likely to achieve challenging goals than are people who rate low on achievement motivation |

| D. | avoid competing with others |

Test your understanding of Psychological Needs as Motivators with