Chapter 10. Gender Stereotypes

10.1 Welcome

Think Like a Scientist

Gender Stereotypes

By:

FAQ

What is Think Like a Scientist?

Think Like a Scientist is a digital activity designed to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. Each activity places you in a different, real-world scenario, asking you to think critically about a specific claim.

Can instructors track your progress in Think Like a Scientist?

Scores from the five-question assessments at the end of each activity can be reported to your instructor. To ensure your privacy while participating in non-assessment features, which can include pseudoscientific quizzes or games, no other student response is saved or reported.

How is Think Like a Scientist aligned with the APA Guidelines 2.0?

The American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major” provides a set of learning goals for students. Think Like a Scientist addresses several of these goals, although it is specifically designed to develop skills from APA Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking. “Gender Stereotypes” covers many outcomes, including:

- Incorporate sociocultural factors in scientific inquiry: Relate examples of how a researcher’s value system, sociocultural characteristics, and historical context influence the development of scientific inquiry on psychological questions [consider development of and response to Implicit Attitudes Test]

- Interpret, design, and conduct basic psychological research: Define and explain the purpose of key research concepts that characterize psychological research [identify independent and dependent variables in a study]

REFERENCES

Bennett, Jessica. (2017, December 30). The #MeToo moment: The year in gender. The New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/30/us/the-metoo-moment-the-year-in-gender.html

Brendl, C. Miguel; Markman, Arthur B.; & Messner, Claude. (2001). How do indirect measures of evaluation work? Evaluating the inference of prejudice in the Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 760–773. doi:10 10371m22-3514.81.5.760

Farrell, Lynn, & McHugh, Louise. (2017). Examining gender-STEM bias among STEM and non-STEM students using the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP). Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 6, 80-90. doi:10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.02.001

Jackson, Sarah M.; Hillard, Amy L.; & Schneider, Tamera R. (2014). Using implicit bias training to improve attitudes toward women in STEM. Social Psychology of Education, 17, 1–20. doi:10.1007/s11218-014-9259-5

Jones, Kristen P.; Peddie, Chad I.; Gilrane, Veronica L.; King, Eden B.; & Gray, Alexis L. (2016). Not so subtle: A meta-analytic investigation of the correlates of subtle and overt discrimination. Journal of Management, 42, 1588-1613. doi:10.1177/0149206313506466

Lane, Kristin A.; Goh, Jin X.; & Driver-Linn, Erin. (2012). Implicit science stereotypes mediate the relationship between gender and academic participation. Sex Roles, 66, 220–234. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-0036-z

McNeely, Connie L., & Vlaicu, Sorina. (2010). Exploring institutional hiring trends of women in the U.S. STEM professoriate. Review of Policy Research, 27, 781–793. doi:10.1111/j.1541-1338.2010.00471.x

Moss-Racusin, Corinne A.; Dovidio, John F.; Brescoll, Victoria L.; Graham, Mark J.; & Handelsman, Jo. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,109, 16474–16479. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211286109

Rothermund, Klaus, & Wentura, Dirk. (2004). Underlying processes in the Implicit Association Test: Dissociating salience from associations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133, 139–165. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.133.2.139

Swanson, Jane E.; Rudman, Laurie; & Greenwald, Anthony G. (2001). Using the Implicit Association Test to investigate attitude-behaviour consistency for stigmatised behaviour. Cognition & Emotion, 15, 207–230. doi:10.1080/02699930125706

10.2 Introduction

This activity invites you to test the claim that many of us believe gender stereotypes unconsciously (implicitly) even if we are not aware that we do so consciously (explicitly). First, you’ll take an Implicit Association Test (IAT) to assess how quickly you associate words related to women and men with the liberal arts or sciences. You’ll then examine evidence about whether people hold implicit, unconscious biases. Next, you’ll explore alternative explanations for the IAT findings. Finally, you’ll consider the source of the evidence about potential gender biases.

10.3 Identify the Claim

1.

Identify the Claim

10.3.1 Do People Still Hold Gender Biases?

Obvious, shocking instances of sexism in the workplace have been in the news, particularly related to the #MeToo movement (Bennett, 2017). But even people who don't act in overtly sexist ways and don’t think they are sexist can have implicit gender biases, beliefs of which they are unaware. And the subtle discrimination that can result from implicit biases can be even more damaging to women’s careers than obvious discrimination because it occurs more frequently (Jones & others, 2016).

To identify these implicit attitudes, researchers developed Implicit Association Tests (IATs), which measure how quickly and accurately people connect concepts. For example, one version of the IAT asks you to match science-related words like “physics” or liberal arts-related words like “literature” with male- and female-related words like “husband” or “sister.”

Take this version of the IAT to see if you hold any unconscious biases about women in science fields. (And don’t worry; we’re not keeping your data or sharing it with your instructor!) You will be presented with a set of words to classify into categories. You must categorize items as quickly and accurately as possible. If you go too slowly or make too many errors, your score cannot be interpreted.

Important information:

- Place your index fingers on the 'Z' and '/' keys and keep them there to enable you to respond quickly.

- You will see category labels—male, female, science, or liberal arts—on each side of the screen. The ones on the left go with the 'Z' key and the ones on the right go with the '/' key.

- When a word pops up in the middle, you need to categorize it properly. So, if it says “Science” on the left, and the word “Astronomy” pops up in the middle, you would hit the 'Z' key on the left.

- It’s OK if you make some mistakes. It’s more important to go fast.

- If you use a tablet, you may attach a keyboard to your device and press the appropriate keys or use the buttons on the screen to make your selections.

10.3.2 Do You Have Implicit Gender Biases?

After taking the IAT, you may have discovered that you have unconscious gender biases. If you don’t have them, that’s great. But don’t worry if you do; you’re probably in the majority.

Question

10.4 Evaluate the Evidence

2.

Evaluate the Evidence

10.4.1 Implicit Gender Biases about Fields of Study

People hold implicit biases and explicit biases, both of which can influence behavior. Implicit biases are based on beliefs outside of our awareness, whereas explicit biases are based on beliefs of which we are aware.

Several studies have found that both female and male university students hold implicit biases about women in science, which might guide students’ decisions about their fields of study (Farrell & McHugh, 2017). In one study, interest in science was not predicted by explicit biases, what people say they think about women in science (Lane & others, 2012). However, interest in science was predicted by implicit biases, students’ unconscious beliefs. Implicit biases, then, contributed to the outcome that women were less likely than men to consider choosing a major in math or science.

10.4.2 Studying Implicit Biases

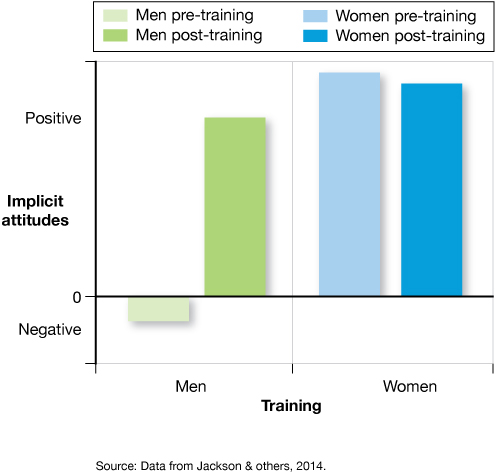

Can implicit and explicit biases be changed by diversity training? In one study, researchers examined implicit beliefs among faculty members in the sciences by giving male and female participants an IAT before and after a half-hour diversity training session (Jackson & others, 2014). Participants were also asked about their explicit attitudes, their conscious beliefs about women in the sciences.

So, researchers examined the effects of two variables—gender (female and male) and diversity training (pre-training and post-training)—on two other variables—implicit attitudes about women in science using an IAT and explicit attitudes about women in science.

What are the independent variables in this study? Click as many answers as are applicable.

Question

What are the dependent variables in this study? Click as many answers as are applicable.

Question

10.4.3 Implicit Gender Biases for Fields of Study?

Before diversity training, the female professors had more positive implicit views of women in scientific fields than their male counterparts (Jackson & others, 2014). Female professors did not show an increase in positive attitudes after diversity training, likely because they already held relatively positive beliefs. However, male professors did show more positive attitudes after diversity training. These results suggest that we may have implicit gender biases, but they can be altered by diversity training.

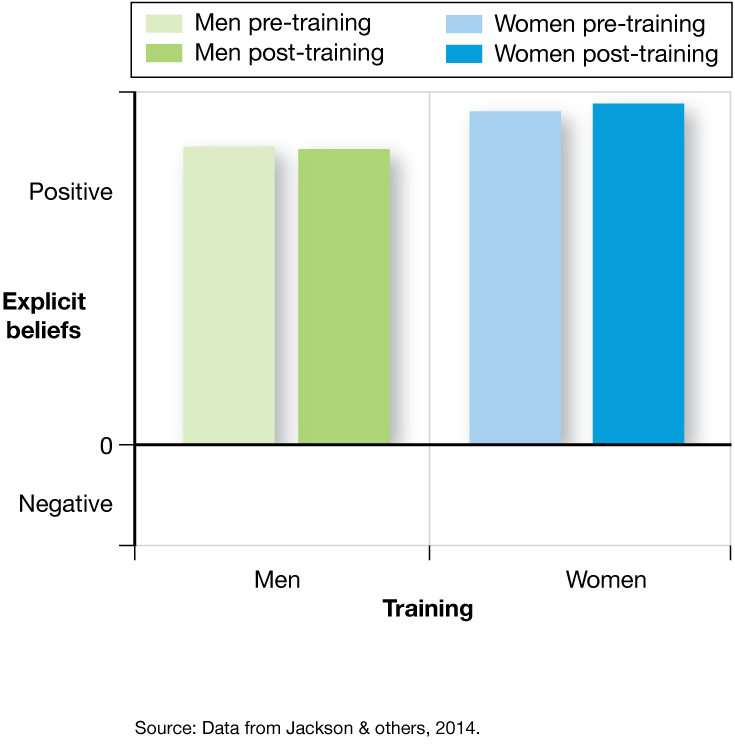

10.4.4 Diversity Training and Explicit Beliefs

The researchers also measured explicit beliefs before and after diversity training (Jackson & others, 2014). Participants were asked how favorably they viewed women in scientific fields and how much they agreed with stereotypes about women in science. Women had higher scores than men on both measures before training and after training, but neither women nor men changed their explicit beliefs following the diversity training.

10.4.5 Men’s Implicit Beliefs vs. Men’s Explicit Beliefs

The researchers found that male scientists hold implicit beliefs about female scientists that can often be made more positive by diversity training. Meanwhile, men’s explicit beliefs do not tend to be affected by that diversity training. Why?

These researchers speculate that explicit beliefs are affected by a desire to be socially acceptable. In the case of gender and field of study, it’s more acceptable to say you have positive attitudes toward women in science. The researchers also suggest that implicit attitudes are a better indication of true attitudes. If diversity training works, then it should influence implicit beliefs.

10.5 Consider Alternative Explanations

3.

Consider Alternative Explanations

10.5.1 Are There Other Explanations for This Gender Bias?

The researchers concluded that IATs can uncover gender biases that people don’t realize they have or are unwilling to report. But thinking like a scientist involves asking if there are other explanations for these research findings. Some researchers have wondered whether we respond more quickly to situations we experience more frequently (Brendl & others, 2001; Rothermund & Wentura, 2004). For example, we may be more accustomed to associating men and science, so we react more quickly when we see this more common situation. We might not have a more negative implicit bias of women in science than men in science. It may simply be that women in science are less familiar to us.

10.5.2 Googling Famous Scientists

Open another window or tab on your computer and take a minute to Google “famous scientists.” Come back when you’re done.

Question

Question

5FT3bOflU/U6GX6YIMzbBV/TfytftSvWqmDphUv5hrsmpmR37D0XUTEgrtXmTcYTIf+efeB8VHSzgyXmh53pAm8xjFTP2pJ8wgpryQx0gGXvnRLZd9XnhVUjpGH3fRh0nl87k/RvY0AUL9wXIXn36cgZNxGQv9Ua3YG3Wmcal3nT225Y

10.5.3 Seeing More Male Scientists

College students are more likely to have male professors than female professors in scientific fields, particularly at higher academic ranks (McNeely & Vlaicu, 2010). And we are more likely to see male scientists on TV shows or in movies. The five original main characters (pictured below) in the TV show, The Big Bang Theory, for example, were four male scientists and a waitress/aspiring actress. Only over time did other female scientist characters get more prominent roles on the show. It wouldn’t be surprising that we can more quickly associate men with science than women with science.

Question

DAg0RD/VQtpH1o1AxYl9IpARoouSpxgO1IfXm6TylLQXQl1eDSJtvjijCXAwFH7gjXOJpaPd0/O+aZj/9W7zLVUxisLkxSt0wt7PXB/UB3BGcFsJdkaO/kZwRJ5EgjQOeykbDkq13cSD8v6eWGakGiB8+g3YsrHjv3ZqOCbW/bzQ6jQ9PiJkwwlDnHENXhVpVAHOhhRIQR5D7o4YPSMSSWw8NGZitO8MwA/XtT5tWtYyui59whG8MFfSG4Dbnx7h+0SCNNY5OnVgxmVBbY6+LBhTQMfRbdgfVkRJSsOqbQb1aKzG1sB1qnXR04NFxvZY7rGZSJZ8Vc3r1+tbxpyLuERc0K5l9/gbnXd+AA7QvZsDWFngzPKKMYHouzYMUyEB2r4iI0UgSM68NSmGnE6rF4Nmwkkh+Frr1CiJflZPgoa21WiEUuNXpFthcxp9O+4J0b7zEbVr36jb8c3zPiQfTMxDJNdRiMz1/H+hCE7PNNENRI6oQnC9AU2lgFR+OV0dw/ZxT6lz9sBa655dvYi6qVXQkmrLXPFLsNPTtOrf5ElgYlZf3LkLsX5Zc3eMuoK8IB+58E2f51V7Zdamf3D7Zo7cxmZxZHz6hWMBjBzirDU64sOTT2Mj+WKjIfEQX2b2iwBI/KaKOjfXQiebU56Ylt4wyLxoGrldEYZxiymIq7ZqKYRkWZkDq3YGKCZKWttK5wZhXg6xvkil1u6dzglZlUnaRrcCYoAx/6GKOY3xE+JB6DvzGK0tFA+qxsfYKbidMYZcOHK4hsj2DlecoImjHq+elZWDXaTmtTqS9tJ8y0+HX89LTvyeqRWRC5jk1PPLzeS0VsRAQj14HfJeW6bNaaPHsAVPHk0Tg8NvbNH8/sH+7gMO+yI9ATknVpEu3UDFTNw3t+tcyoAKAeGPNT0+blIIDty6ItJ7rtXsciYcNvTuVdZkxv4JhcKVPR4q7IVZvumgWhpRbuCxQTRDLXoOhQ==10.5.4 IATs Really Do Uncover Biases

Although there are alternative explanations for some IAT findings, research suggests that IATs are successful in uncovering biases (Swanson & others, 2001). Let’s explore one study about smoking, which has a kind of stigma attached to it. In this study, smokers reported more positive attitudes toward smoking than nonsmokers when asked to explicitly rate smoking on scales that ranged from ugly to glamorous and unsociable to sociable.

On an IAT, however, both smokers and nonsmokers showed negative attitudes toward smoking. Smokers might justify their behavior out loud, but they still seem to internalize the stigma. These results suggest that people say the “right” thing about a stigmatized belief or behavior when it’s socially desirable to do so, but an IAT works to uncover their implicit beliefs.

10.6 Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4.

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

10.6.1 IATs and True Beliefs

Let’s consider explicit measures and implicit measures as sources of information about our beliefs. As we’ve discovered in this activity, the IAT is more likely to be an objective assessment of our true beliefs than our stated beliefs on an explicit measure. So, an implicit measure is a better source of information about our beliefs than an explicit measure. But when IATs were first introduced, people didn’t want to believe them. It can be disturbing to realize that we may harbor biases of which we’re unaware, especially when they indicate we have a socially undesirable belief.

10.6.2 IATs and True Beliefs

Although it might be difficult to accept when we have negative implicit attitudes, becoming aware of them is often the first step in addressing the impact of biased behaviors. Let’s look at one example of an implicit measure as a source of information about beliefs. One study examined science professors’ perceptions of fictional applicants for a lab position (Moss-Racusin & others, 2012). The study asked professors to rate one of two applications that were identical except for the name. Applications with the name “John” were rated higher, on average, than applications with the name “Jennifer.” And “John” was offered an average starting salary several thousand dollars higher than “Jennifer.” Remember, the applications were identical except for the name! When we want to understand people’s beliefs, we will probably get better information by looking at implicit measures—and not just explicit measures.

10.7 Assessment

5.

Assessment