Chapter 14. Tracking Mental Illness Online

14.1 Welcome

Think Like a Scientist

Tracking Mental Illness Online

By:

FAQ

What is Think Like a Scientist?

Think Like a Scientist is a digital activity designed to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. Each activity places you in a different, real-world scenario, asking you to think critically about a specific claim.

Can instructors track your progress in Think Like a Scientist?

Scores from the five-question assessments at the end of each activity can be reported to your instructor. To ensure your privacy while participating in non-assessment features, which can include pseudoscientific quizzes or games, no other student response is saved or reported.

How is Think Like a Scientist aligned with the APA Guidelines 2.0?

The American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major” provides a set of learning goals for students. Think Like a Scientist addresses several of these goals, although it is specifically designed to develop skills from APA Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking. “Tracking Mental Illness Online” covers many outcomes, including:

- Interpret, design, and conduct basic psychological research: Describe research methods used by psychologists including their respective advantages and disadvantages [compare telephone surveys versus online searches as methods of collecting data]

- Demonstrate psychology information literacy: Interpret simple graphs and statistical findings [understand online search data presented in graphs]

REFERENCES

Angermeyer, M. C., & Schomerus, G. (2017). State of the art of population-based attitude research on mental health: A systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 26, 252-264. doi:10.1017/S2045796016000627

Ayers, John W.; Althouse, Benjamin M.; Allem, Jon-Patrick; Rosenquist, J. Niels; & Ford, Daniel E. (2013). Seasonality in seeking mental health information on Google. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44, 520-525. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.012

Ayers, John W.; Althouse, Benjamin, M.; Leas, Eric C.; Dredze, Mark; & Allem, Jon Patrick. (2017). Internet searches for suicide following the release of 13 Reasons Why. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177, 1527-1529. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3333

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/brfss/

Helft, Miguel. (November 11, 2008). Google uses searches to track flu’s spread. New York Times. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2008/11/12/technology/internet/12flu.html

Lazer, David; Kennedy, Ryan; King, Gary; & Vespignani, Alessandro. (2014a). The parable of Google Flu: Traps in big data analysis. Science, 343, 1203-1205. Retrieved from gking.harvard.edu/files/gking/files/0314policyforumff.pdf

Lazer, David; Kennedy, Ryan; King, Gary; & Vespignani, Alessandro. (2014b). Google Flu Trends still appears sick: An evaluation of the 2013-2014 flu season. Available at SSRN: ssrn.com/abstract=2408560, dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2408560 or gking.harvard.edu/files/gking/files/ssrn-id2408560_2.pdf

Lohr, Steve. (March 28, 2014). Google Flu Trends: The limits of big data. New York Times. Retrieved from bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/03/28/google-flu-trends-the-limits-of-big-data/

14.2 Introduction

This activity invites you to test the claim that we can track patterns of mental illness, like anxiety disorders, by analyzing online searches. First, you’ll conduct a search to explore what comes up when you Google “anxiety.” Then, you’ll look at evidence from a study that analyzed online searches to track patterns in mental illness. Next, you’ll explore alternative explanations for these findings based on your own online searches. Finally, you’ll examine internet search data—a type of “big data”—as a source of information about mental health patterns.

14.3 Identify the Claim

1.

Identify the Claim

14.3.1 Tracking Mental Illness

Is depression more common in the winter? Are eating disorders more frequent in some countries than in others? Does anxiety spike around the holidays? When we understand disease patterns, we are better able to target treatment and prevention programs.

Unfortunately, many of the most common techniques used to track patterns are flawed. Researchers can’t use treatment records because most people with a mental illness never get treated. Telephone surveys are often used, but they are expensive to conduct. And, telephone surveys can lead to unrepresentative samples because mobile phone numbers are often not published and because telephone service is not universal in some parts of the world (Angermeyer & Schomerus, 2017). There’s also the question about how people respond to telephone questions about their mental health. Would you tell a researcher your mental health history over the telephone?

14.3.2 Take a Survey About Health Problems

One of the largest and longest-running telephone surveys is the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, run by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Participants are asked about different types of health problems, including mental health, physical health, and exposure to environmental hazards like mold. Click whether you would feel comfortable (or not) admitting to dealing with the issue mentioned in each of these questions from an interviewer.

QUESTIONS FROM THE BEHAVIORAL RISK FACTOR SURVEILLANCE SYSTEM SURVEY |

I’D ADMIT TO THIS. |

I’D NEVER ADMIT TO THIS. |

|---|---|---|

“Have you ever been told by a health professional that you have high blood pressure?” |

||

“During the past 12 months, have you had an episode of asthma or an asthma attack?” |

||

“During the past 30 days, about how often did you feel so depressed that nothing could cheer you up?” |

||

“About how often during the past 30 days did you feel nervous?” |

||

“Do you currently have mold in your home?” |

||

“Has your household air been tested for the presence of radon gas?” |

||

“Since 2005, have you had a tetanus shot?” |

||

“During what month and year did you receive your most recent flu vaccine?” |

QUESTIONS FROM THE BEHAVIORAL RISK FACTOR SURVEILLANCE SYSTEM SURVEY

I’D ADMIT TO THIS.

I’D NEVER ADMIT TO THIS.

14.3.3 Online Searches and Mental Illness

Can Google read your mind? Increasingly, researchers analyze what is known as “big data,” enormous amounts of computerized information. Some researchers speculate that our online search history, a treasure trove of big data, can provide a window into our thinking, behavior, and experiences. Researchers believe online searches could even be analyzed to track patterns of mental illness. For example, in the weeks following the release of 13 Reasons Why, the Netflix series focusing on teen suicide, Google searches for the term “suicide” spiked about 20% (Ayers & others, 2017). Researchers think we might Google terms like “suicide” even if we aren’t willing to tell a close friend we are suffering from symptoms of psychopathology.

Question 1.

14.4 Evaluate the Evidence

2.

Evaluate the Evidence

14.4.1 Testing the Claim

To test the claim that Google search frequencies mirror the frequencies of mental illness in the population, researchers analyzed all Google searches in the United States and Australia to determine the frequencies of the following search terms (Ayers & others, 2013):

|

|

Online searches for mental illness typically occur when someone develops a disorder, has a recurrence of that disorder, or finds their symptoms getting worse. The researchers were interested in whether there might be seasonal patterns in the overall number of online searches, which would match suspected seasonal trends in rates and severity of mental illness. If mental illness is more common in the winter than in the summer, the researchers would expect more Google searches for metal illnesses in the winter.

14.4.2 Summer vs. Winter

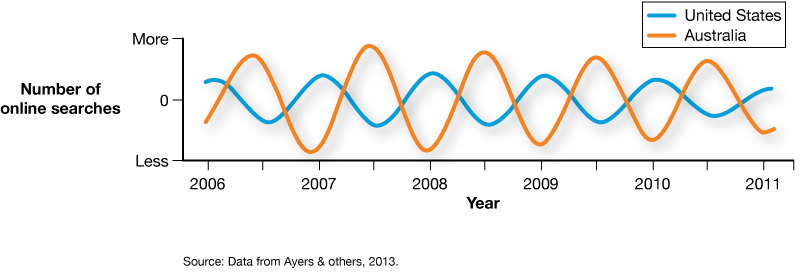

For all the mental illnesses the researchers studied—depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and so on—searches increased in the winter and decreased in the summer. These findings couldn’t be attributed to something going on in the world, like a war or a natural disaster, because the seasons in the United States and Australia are opposite of one another. As you can see in the graph here, U.S. searches peaked when Australian searches were at their lowest. Why? Because summer in the United States occurs during the Australian winter, and winter in the United States coincides with the Australian summer.

Question 2.

14.5 Consider Alternative Explanations

3.

Consider Alternative Explanations

14.5.1 What Do Google Searches Really Measure?

Do Google searches actually measure patterns of mental illness? Or is there an alternative explanation for these findings?

The researchers think that Google searches are accurate measures of how common these disorders are in the population (Ayers & others, 2013). Their methods eliminated some problems with other types of research, including people’s reluctance to answer questions truthfully, such as in a telephone survey. Their research methods also avoid the possibility of prompting answers. When asked about depression, for example, you think about depression, and you might report symptoms you hadn’t thought about otherwise. In an internet search, however, you provide information about a mental illness without being asked. So a Google search shows your natural behavior rather than your prompted behavior or your behavior in the laboratory.

14.5.2 Googling Anxiety

But what does it really mean when you Google a mental illness? Can an online search engine know you’re anxious? Let’s explore alternative explanations for what online searches really indicate. Open another browser window or tab on your computer, and search for “anxiety” using a search engine. As you scroll through the first several pages of results, note the different types of Web sites. Then come back here and click off each of type of Web site you found. We’ll come back to your answers in the next screen.

Question

14.5.3 What Are We Really Searching For?

On the previous screen, you reported the types of Web sites you found from an online search for “anxiety.” Were all of the sites about anxiety disorders? [] It’s possible that people searching for “anxiety” are not referring to anxiety disorders in people. Maybe they just have an anxious dog. Similarly, people searching for “depression” might mean an economic depression, something that tends to pop up toward the top of online searches.

14.5.4 Who Is Conducting the Search?

As we just observed, it’s possible that some people who Google words like “anxiety” and “depression” are searching for something other than mental illnesses. But realistically, this probably only reflects a small proportion of searches. As you saw when you Googled “anxiety,” most of the results gave us information about anxiety disorders—definitions, symptoms, treatment, and other useful information. But what about the person doing the searching? A person who has symptoms of a mental illness may be searching to get more information. Who else might search? List three reasons that someone might search for a mental illness like anxiety, depression, or schizophrenia.

14.6 Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4.

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

14.6.1 Google Searches as a Source of Data: The Case of the Flu

The source of the data for tracking mental illness online was Google searches. So how good are Google searches as sources of data? We don’t know enough about actual rates of mental illness at a given point in time to verify those Google search predictions. But we do have that kind of “real-time” information about another common illness—the flu. To test the value of Google searches as sources of data, we can look at Google Flu Trends, a tool purported to “detect regional outbreaks of the flu a week to 10 days before they are reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention” (Helft, 2008). We know Google Flu Trends’ predictions, and we know the actual U.S. flu data from the CDC. Comparing these data will tell us how well Google predicts an illness.

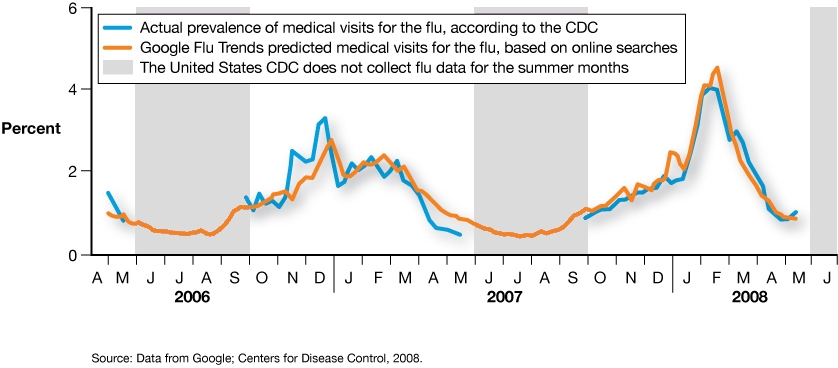

14.6.2 Google Flu Trends vs. the CDC

The graph below shows predictions for the percentage of people in the U.S. with the flu based on Google searches, and the actual percentage of people in the U.S. with the flu that was eventually reported by the CDC. (Note that the initials on the x-axis refer to months. For example, A=April.) As you can see, the plotted lines for those two categories of data seem to match up very closely. At first glance, it appears that Google searches are good predictors for the flu. So, Google searchers might be good predictors for mental illness, too.

Question 3.

14.6.3 The Drawbacks of Google Flu Trends

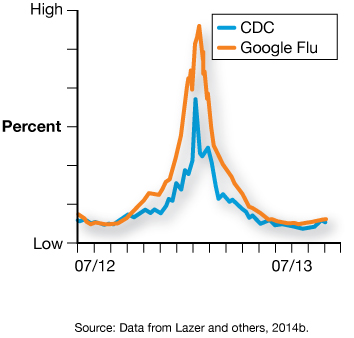

Despite initial appearances, it turns out that Google Flu Trends’ utility as a predictive tool was overstated, an indication that we should be cautious about assigning predictive value to other types of online searches, such as those for mental illnesses. Researchers reported that Google Flu Trends predictions were often higher than the actual percentages reported later by the CDC (Lazer & others, 2014a). They suggested one possible reason: Google’s model might have caused increased flu searches. Try it yourself. Open Google in a new page or tab, and search for symptoms associated with the flu, like "fever and cough." Pay attention to how many results on the first page mention the flu. Return here when you’re done.

Question

dv9SkB7XluSkrMFVlB5MU6urNqXnkN6I5dKAAjVMAaRYGOxRenRTFMGZU+yC99/36ugfQvz+UsSr5W5pjsNYSbvAunCUE4yC3Oy1ilU6EH8ZkS3Q7WI5ybo5zb+RKHlDLkFGSAMhqsFu1qgp52v8Tov9kh68SoSrNaePabJ/XSY7/KOzyUM7sv1McPFhwIjZzB1RX/1VhZO+K4G3En3PlViBtP8=14.6.4 Google Flu Trends Overestimates Outbreaks

Seeing results like these might make you more likely to search for additional information on the flu, even though you never intended to search for the flu. You might only have a cold, which is a more likely diagnosis. Google has since tweaked its flu-tracking tool so it works better, but it still overestimates the flu by about 30% (Lazer & others, 2014b). Some of the same kinds of problems might be occurring with searches for mental illness, although we don’t yet have data to evaluate these searches.

14.6.5 Harnessing Big Data: A Compromise

Even though Google Flu Trends overestimates the percentage of people with the flu, it’s not completely off. Combining it with the CDC data leads to better predictions than either on its own (Lohr, 2014). Researchers have observed that more traditional methods, like survey research, can be improved by using methods from big data analyses (Lazer & others, 2014a). Their idea is to analyze data from both “traditional and new sources,” which provides “a deeper, clearer understanding of our world.” Other researchers can learn from this advice as they improve the tracking of mental illness. Early indicators from Google Flu Trends indicate that online searches – whether of physical illness or mental illness – might be useful predictors if they’re used along with other sources of information.

14.7 Assessment

5.

Assessment