Chapter 15. Ketamine

15.1 Welcome

Think Like a Scientist

Ketamine

By:

FAQ

What is Think Like a Scientist? Think Like a Scientist is a digital activity designed to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. Each activity places you in a different, real-world scenario, asking you to think critically about a specific claim.

Can instructors track your progress in Think Like a Scientist? Scores from the five-question assessments at the end of each activity can be reported to your instructor. To ensure your privacy while participating in non-assessment features, which can include pseudoscientific quizzes or games, no other student response is saved or reported.

How is Think Like a Scientist aligned with the APA Guidelines 2.0? The American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major” provides a set of learning goals for students. Think Like a Scientist addresses several of these goals, although it is specifically designed to develop skills from APA Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking. “Ketamine” covers many outcomes, including:

- Interpret, design, and conduct basic psychological research: Define and explain the purpose of key research concepts that characterize psychological research [identify independent and dependent variables in a study]

- Use scientific reasoning to interpret psychological phenomena: Ask relevant questions to gather more information about behavioral claims [consider how to conduct a better double-blind experiment]

REFERENCES

aan het Rot, Marije; Collins, Katherine A.; Murrough, James W.; Perez, Andrew M.; Reich, David L.; Charney, Dennis S.; & Mathew, Sanjay J. (2010). Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biological Psychiatry, 67, 139–145. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.038

Andrade, Chittaranjan. (2017). Ketamine for depression, 1: Clinical summary of issues related to efficacy, adverse effects, and mechanism of action. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78, e415-e419. doi:10.4088/JCP.17f11567

Hamilton, Jon. (2012, January 31). 'I wanted to live': New depression drugs offer hope for toughest cases. Morning Edition, National Public Radio. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2012/01/31/146096540/i-wanted-to-live-new-depression-drugs-offer-hope-for-toughest-cases

Loo, Colleen. (2018). Can we confidently use ketamine as a clinical treatment for depression?. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5, 11-12. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30480-7

Pollack, Andrew. (2014, December 9). Special K, a hallucinogen, raises hopes and concerns as a treatment for depression. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/10/business/special-k-a-hallucinogen-raises-hopes-and-concerns-as-a-treatment-for-depression.html

Ryan, Christopher James, & Loo, Colleen. (2017). The practicalities and ethics of ketamine for depression. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4, 354-355. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30155-4

Schwartz, Jaclyn; Murrough, James W.; & Iosifescu, Dan V. (2016). Ketamine for treatment-resistant depression: Recent developments and clinical applications. Evidence Based Mental Health, 19, 35-38. doi:10.1136/eb-2016-102355

Singh, Ilina; Morgan, Celia; Curran, Valerie; Nutt, David; Schlag, Anne; & McShane, Rupert. (2017). Ketamine treatment for depression: Opportunities for clinical innovation and ethical foresight. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4, 419-426. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30102-5

Stix, Gary. (2013, September 12). Is ketamine right for you? Off-label prescriptions for depression pick up in small clinics, part 2. Retrieved from http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/talking-back/2013/09/12/is-ketamine-right-for-you-off-label-ketamine-prescriptions-for-depression-pick-up-in-small-clinics-part-2/

Zarate, Carlos A.; Singh, Jaskaran B.; Carlson, Paul J.; Brutsche, Nancy E.; Ameli, Rezvan; Luckenbaugh, David A.; ... & Manji, Husseini K. (2006). A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 856–864. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856

15.2 Introduction

This activity invites you to test the claim that ketamine, sometimes sold illegally as the street drug "Special K," is a promising treatment for depression. First, you’ll hear three audio clips from a radio show that interviewed a patient who benefited from ketamine and a scientist who studies ketamine. You will then examine the current evidence about the effectiveness of ketamine as a treatment for depression, and consider alternative explanations for these findings. Finally, you will evaluate sources for information about how well ketamine works as an antidepressant.

1

Identify the Claim

15.3.1 Can a Street Drug Treat Depression?

Can a street drug treat depression? In the chapter on therapies, you learned about a promising new treatment for depression, an experimental drug called ketamine (Singh & others, 2017; Loo, 2018). Ketamine is used legally as an anesthetic, but it is better known as the illegal party drug Special K. More recently, people suffering from depression have been treated with lower doses of the drug with surprisingly successful results. For many people, ketamine reduces symptoms of depression very quickly, but its use is controversial (Zarate & others, 2006).

15.3.2 The Controversy Surrounding Ketamine

Let’s explore the controversy surrounding ketamine. We’ll start by playing you audio clips from a news show on National Public Radio. First, you’ll hear from Christopher Stephens (pictured below), a 28-year-old special-education assistant and martial arts instructor who lives in northern California. Stephens tells reporter Jon Hamilton that he had tried about ten different antidepressants or anti-anxiety drugs; many had negative side effects and none reduced his depression. In fact, his depression become so deep, Stephens started considering suicide. Let’s listen.

STEPHENS: I went on the Internet, and I started researching ways to end your life. You know, a lot of people think oh, I can down a bottle of Tylenol, and that'll do it. What that'll actually do is kill your liver, and you slowly die - which is not a good way to go. I wanted to research the most efficient and painless way to do it.

HAMILTON: But Stephens wanted to do something good before he died, something that might help other people avoid the hopelessness that he was feeling. So he called up the University of California-San Francisco, and offered himself up as a sort of human lab animal. He thought maybe scientists could learn something about depression by studying his brain. That call got Stephens referred to Carlos Zarate, a brain scientist at the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

15.3.3 The Claim About Ketamine

As you learned in the chapter on therapies, many antidepressants affect serotonin, and some affect both serotonin and norepinephrine. But Dr. Zarate, the brain scientist to whom Stephens was referred, has a different idea. Let’s hear again from reporter John Hamilton talking about Dr. Zarate.

HAMILTON: He's thinks there's another chemical that gets much closer to the problem. It's called glutamate. And that's where ketamine comes in. The anesthetic-turned club drug seems to act directly on the glutamate system. Zarate tells me he was intrigued when he began hearing anecdotal reports that ketamine could relieve depression almost instantly. But as a scientist, he says, he was thinking the reports sounded too good to be true.

Question 1. The Claim About Ketamine

2

Evaluate the Evidence

15.4.1 The Evidence for Ketamine as an Antidepressant

Let’s listen to another audio clip. This one discusses the evidence for ketamine as an antidepressant. It begins with Dr. Zarate.

ZARATE: In the field, there was really a question whether people really did believe these initial observations because it was so dramatic. And so we decided to test this in a controlled study.

HAMILTON: The study involved 17 patients with depression. They were people like Christopher Stephens, who had tried lots of medications without success. After a single dose of ketamine, 12 of the 17 got better within hours. And they stayed better for a week or more.

The result got international attention. And since then, Zarate has given ketamine to many more patients, including Stephens. Stephens himself has vivid memories of the day he got ketamine. It was a Monday morning, and he woke up feeling really bad. His mood was still dark when doctors put in an IV and delivered the drug.

STEPHENS: Monday afternoon, I felt like a completely different person. It was, you know, same day – same-day effects and, you know, I woke up Tuesday morning and I said wow, there's stuff I want to do today. And I woke up Wednesday morning and Thursday morning. And for the first time in - I don't even remember, I actually wanted to do things. I wanted to live life.

HAMILTON: About 18 months ago, researchers at Yale found a possible explanation for ketamine's effectiveness. It seems to affect the glutamate system in a way that causes brain cells to form new connections. Researchers have long suspected that stress and depression weaken some connections among brain cells. Ketamine appears to reverse the process.

Question 2. The Evidence for Ketamine as an Antidepressant

15.4.2 The Side Effects of Ketamine

In these early studies, ketamine relieved depression within hours for many people suffering from depression. Unfortunately, ketamine can have serious side effects. For example, the table below lists side effects reported in one study of ketamine as an antidepressant (aan het Rot & others, 2010). We pick up the audio clip with Dr. Zarate again.

ZARATE: Feel an out-of-body experience, seeing trails of light. Their memory might be a bit foggy.

HAMILTON: Also, people can get hooked on ketamine, and habitual use has been linked to serious health problems. So scientists have been checking out other drugs that also tweak the glutamate system. One is a pill called riluzole, which is less potent than ketamine. Christopher Stephens has been taking it ever since his ketamine treatment. It has been more than a year now, and he says his depression hasn't returned.

| Side effects experienced by at least one patient in a study of ketamine for depression |

|---|

|

Abnormal sensations Blurred vision Diminished mental capacity Dizziness or faintness Feeling drowsy or sleepy Feeling strange or unreal Headache Hearing or seeing things Numbness or tingling Poor coordination or unsteadiness Poor memory Rapid or pounding heartbeat Weakness or fatigue |

| Source: Information from aan het Rod & others, 2010. |

15.4.3 Ketamine: An Experiment

Let’s look at one of the ketamine experiments. Dr. Zarate led a study of 18 patients who were diagnosed with major depression and had been treated unsuccessfully with antidepressants at least twice (Zarate & others, 2006). Through random assignment, Dr. Zarate placed these 18 patients in one of two groups—9 received ketamine and 9 received a placebo. The study was double-blind; neither the patients nor their doctors knew which they had received.

Following treatment, the researchers measured patients’ levels of depression. The researchers’ operational definition of depression was the patients’ scores on a standardized test of depression symptoms.

Question 3. Ketamine: An Experiment

Question 4. Ketamine: An Experiment

15.4.4 Ketamine Versus Placebo

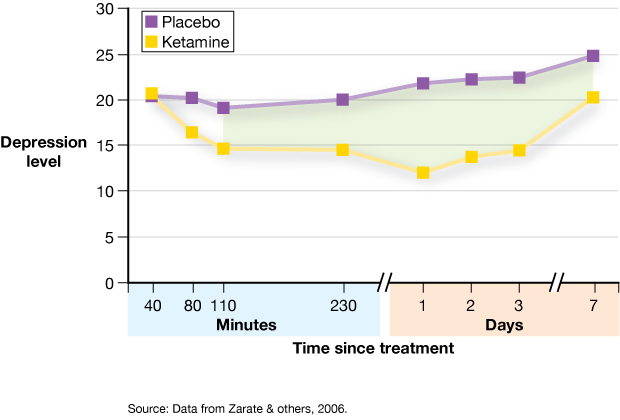

Dr. Zarate’s study found “dramatic” results (Zarate & others, 2006). Less than two hours after treatment, patients who received ketamine were significantly less depressed, on average, than those who received placebo. More than a third of the ketamine patients maintained this improvement, compared with the placebo group, for a week or longer. You can see Zarate’s results in the graph here. The shaded portion indicates where the two groups were significantly different. Remember, this is based on just one dose of ketamine. This study, and others, do indeed support the effectiveness of ketamine as an antidepressant, at least in the short term (Singh & others, 2017). And a short-term success might give patients a chance to get a longer-term treatment started with antidepressants that can take weeks to begin working.

Question 5. Ketamine Versus Placebo

3

Consider Alternative Explanations

15.5.1 Ketamine Effect or Placebo Effect?

Is ketamine really a fast-acting antidepressant? Or is there another explanation? Maybe it’s a placebo effect—and we don’t mean the actual placebo. We’ll explain. People who take ketamine almost certainly feel its effects. And the researchers used a saline solution as the placebo, which would not have a noticeable effect. So, Dr. Zarate’s study may not have been truly “double-blind”: Both the participants and the clinicians probably realized exactly who received ketamine or a placebo, which may have affected each participant’s response.

Instead of saline solution as a placebo, other researchers suggest using “an active control,” a substance with noticeable effects. They could use, for example, a substance similar to ketamine, such as another anesthetic, that doesn’t affect the glutamate system (aan het Rot & others, 2010). This would make it more difficult for the participants and researchers to know who was in the ketamine condition or in the control condition.

Question 6. Ketamine Effect or Placebo Effect?

4

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

15.6.1 Should Ketamine Be Used as an Antidepressant?

Ketamine has received a lot of press for its potential as a fast-acting antidepressant. And research does seem to support its effectiveness, at least as a short-term solution (Andrade, 2017). The problem is that ketamine is not approved for use as an antidepressant by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is still considered experimental as a treatment for depression. So, there are currently no federal guidelines for its use (Ryan, 2017). Moreover, most of the evidence for ketamine as a treatment for depression is based largely on “testimonial and anecdote” (Stix, 2013). In the words of one researcher, “enthusiasm for ketamine as an antidepressant has run ahead of the evidence” (Andrade, 2017).

Ketamine is legitimately prescribed as an anesthetic, though, so physicians may legally prescribe it “off label” to people suffering from depression. This allows pop-up clinics to offer off-label ketamine prescriptions at hundreds of dollars a dose, which are usually not covered by insurance (Pollack, 2014).

15.6.2 Misleading Information about Ketamine as an Antidepressant

Pop-up clinics offering off-label ketamine to treat depression have become a lucrative business, and advertising encourages the use of ketamine for this purpose. Just look at the mock ad below, which is based on real ads for ketamine clinics. Ads like this often provide vague or misleading information about ketamine. Read the ad, and then read the text in the accompanying bubbles to learn how each of the ad’s statements is potentially problematic.

15.6.3 Consider the Conflicts of Interest, Plus a Warning

You just read about several ways in which important information was not provided by the mock ad for a ketamine clinic. The bottom line is that the people who run the clinic may have conflicts of interest. Those who run the clinics may be motivated by the desire to help patients, or they may be motivated by the desire to make money. In the meantime, research continues, and one day ketamine or a new drug aimed at the glutamate system may become available as a treatment for depression. In the meantime, if you or a loved one is diagnosed with depression, think like a scientist as you consider possible treatments.

Here’s one final word about using ketamine for treating depression: We do not endorse the off-label use of ketamine for treating depression, particularly because there is currently little information on its long-term effects (Loo, 2018; Schwartz & others, 2016). And the street drug version of ketamine can be downright dangerous. If you are suffering from depression, seek reputable mental and physical healthcare providers.

5

Assessment