Chapter 3. ESP

3.1 Welcome

Think Like a Scientist

ESP

By:

With the assistance of

FAQ

What is Think Like a Scientist? Think Like a Scientist is a digital activity designed to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. Each activity places you in a different, real-world scenario, asking you to think critically about a specific claim.

Can instructors track your progress in Think Like a Scientist? Scores from the five-question assessments at the end of each activity can be reported to your instructor. To ensure your privacy while participating in non-assessment features, which can include pseudoscientific quizzes or games, no other student response is saved or reported.

How is Think Like a Scientist aligned with the APA Guidelines 2.0? The American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major” provides a set of learning goals for students. Think Like a Scientist addresses several of these goals, although it is specifically designed to develop skills from APA Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking. “ESP” covers many outcomes, including:

- Interpret, design, and conduct basic psychological research: Describe the fundamental principles of research design [consider effect of manual versus computerized randomization]

- Incorporate sociocultural factors in scientific inquiry: Relate examples of how a researcher’s value system, sociocultural characteristics, and historical context influence the development of scientific inquiry on psychological questions [acknowledge role of prior belief when performing research]

REFERENCES

Fram, Alan. (2007). That’s the spirit: One-third of people believe in ghosts—and some report seeing one. Associated Press Archive, Record No. d8SGT3CG0. Associated Press: Washington, DC.

French, Chris. (2012). Halloween challenge: Psychics submit their powers to a scientific trial. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/science/2012/oct/31/halloween-challenge-psychics-scientific-trial

Goldsmiths, University of London. (2012). Psychics fail ‘Halloween Challenge’ at Goldsmiths [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.gold.ac.uk/news/pressrelease/?releaseID=972

Gray, Stephen J., & Gallo, David A. (2016). Paranormal psychic believers and skeptics: A large-scale test of the cognitive differences hypothesis. Memory & Cognition, 44, 242-261. doi:10.3758/s13421-015-0563-x

Hyman, Ray. (2010). Meta-analysis that conceals more than it reveals: Comment on Storm et al. (2010). Psychological Bulletin, 136, 486-490. doi:10.1037/a0019676

Rouder, Jeffrey N.; Morey, Richard D.; & Province, Jordan M. (2013). A Bayes factor meta-analysis of recent extrasensory perception experiments: Comment on Storm, Tressoldi, and Di Risio (2010). Psychological Bulletin, 139, 241–247. doi:10.1037/a0029008

Storm, Lance; Tressoldi, Patrizio E.; & Di Risio, Lorenzo. (2010). Meta-analysis of free-response studies, 1992–2008: Assessing the noise reduction model in parapsychology. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 471–485. doi:10.1037/a0019457

3.2 Introduction

This activity invites you to explore the existence of psychic abilities. First, you’ll identify the claim about extrasensory perception, or ESP. Then, you will explore evidence about the existence of ESP. You’ll also examine how your beliefs about ESP affect how you interpret research on this phenomenon. You will examine alternative explanations for why people believe in ESP despite a lack of evidence that it exists. Finally, you’ll consider the need to ask good questions about science, even when there is a high-quality source of available information, such as a peer-reviewed journal article.

3.3 Identify the Claim

1.

Identify the Claim

3.3.1 Psychic Abilities

Have you ever had a hunch that turned out to be true? Do you believe in clairvoyance, telepathy, or other forms of extrasensory perception (ESP)? As you learned in your textbook chapter on sensation and perception, ESP is the acquisition of information outside of the normal processes of sensation like seeing or hearing. It’s kind of like Bluetooth for your brain. About half of Americans believe in ESP (Fram, 2007). Are you one of them? Later, you can complete a short survey to find out.

3.3.2 Do You Think You Have Psychic Abilities?

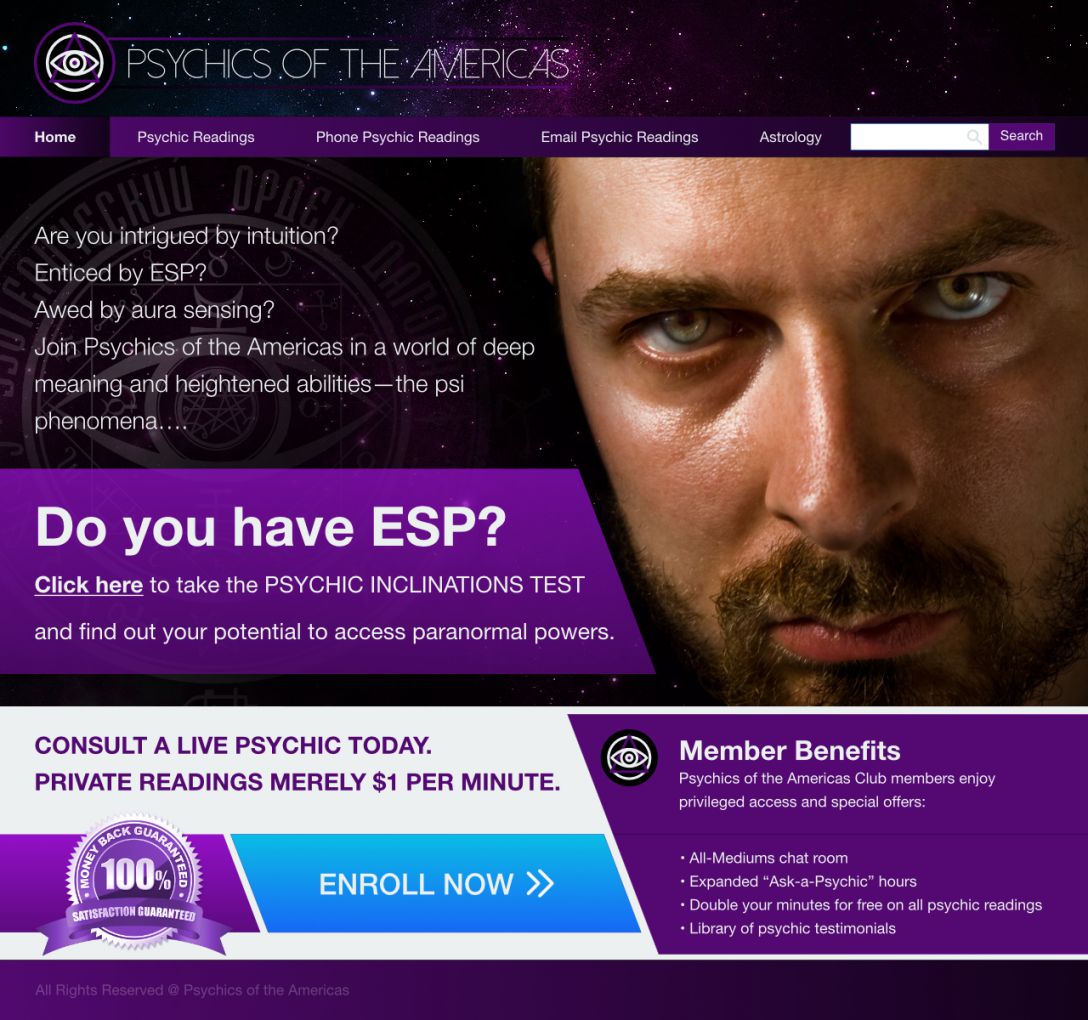

If you are interested in paranormal phenomena, you may have looked for information about ESP online. Googling “Do I have ESP?” yields dozens of sites offering quizzes and exercises that claim to help you recognize or develop this “skill.” As an example, look at this mock Web site, which is similar to many “psychic phenomena” sites online. (You can click the image to enlarge.) On the next screen, you can take the quiz advertised on this site.

3.3.3 Take the Mock Quiz

Imagine you are intrigued by the Web site you just viewed, and you want to take the “psychic inclinations” test. The mock quiz that follows was developed based on actual quizzes available online, and you can try it now. You must complete all 15 questions in this quiz in order to receive your “result” and advance to the next screen of this Think Like a Scientist activity. (Note: Your responses to individual questions will not be saved and your “score” will not be reported to your instructor.)

Complete a short survey to find out if YOU have psychic inclinations! For each item, click either yes or no.

Question

3.3.4 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.5 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.6 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.7 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.8 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.9 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.10 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.11 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.12 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.13 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.14 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.15 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.16 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.17 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3.3.18 Are Some People Psychics?

Question 1.

P/np/pWs4osNDTA9DR97S305Z2QybRf068nz6fT808VIkApMctIWaE+F7oOk3v6CYEt8nfKhNih0IVew7ufRX1h+Xn3KhtxbIWWPWJ4bKv0PcJU9U1QWsmaqLmfYBFabdRtQmhYYuiRZ9E+zCOihZ+kzbHL4m5i1t7evdketkmfGnvTrjDYcqFa3I+5dszSHgdx6dtbERQxW2JY3qCQ36hqAtEpbz7vtKjZD2z92sttawMHag4K+euoX/s5XZPSl6pAbeO6hzr7JifGEJ8rmY+ewP5I9bQL8kQLEryhEjKb1sLeqi3MDxyWUpZAoFqVDMqFJF1l7xJBtKzjx4S/rP6LlKblbthtyzpattRHEk7BkMvwgv+drzQQPUoUlN3C9Pr7ZjY74bBgEroWqf/Ttg6lGq5P76lBVwCgaBSeEKeEIdNkYJEDMW4TA7F9QNVUJH/AuE3l/CTw4ErihkmrfV36I0lp43QyGop7TnoUuBZs7/6YyjzV2ybPY+fofB/JoFa/YgA==Question 2.

IPI4NpwYepbmCl4DxYsu/Ji5OlYPvO/HFenc/7geXhbO0dhjI8IqxLoxCgdxMfT4Nneh3PsCL7hpclAeTUUfSYvd33MHvcUNyU44pI7gqmXSFyR0oIwQAGal6OLI1K7hmhGQOqidcupfXGmNgpy7wa+kevOxJ22307ZXCbMdaJGXi+CCmNrUJAJeJp2DN072MCL6dkcRk1a6GAo7ZltNMybZDml5iLrfUJ0yBIix2Eg9WUR45mffTqHNrTOMVOW+n9usHFdc8Xjxkj9W5v0oQG+qLuXEn7n7UFJrbVFLc8CN8JTZOe3DZW67W0DFPy8MLcN2O2E5FvThf2dz1HNR7ycQRcdLsCBoAGfrtmiD0p//88VEznLDou4uGgp+8DkZbg47ZrNBIN0JIDocdlEA10CS69ZnY1hLvHzIgfr5wnGtxChQ2yv5AD5QXyHMMoz/wlzibcd70QSE9dNOlkuPZPgUSH1htu6a49qscgWTGE4=3.4 Evaluate the Evidence

2.

Evaluate the Evidence

3.4.1 So Is ESP Real?

Although the general public is split about whether ESP is real, only a small number of researchers are actively investigating this topic. The vast majority of psychologists agree that there is no convincing scientific evidence that ESP exists (Hyman, 2010).

So if the evidence is overwhelming, are you wondering why there is any debate at all? Whether or not you asked that question may have something to do with your response to the quiz you just took. We’ll look at the evidence for and against the existence of ESP. But first, let’s examine how scientists investigate ESP.

3.4.2 Putting Psychics to the Test

The following small-scale example shows how ESP can be tested in the lab. Psychologists at the Anomalistic Psychology Research Unit, part of the University of London, put professional psychics Kim Whitton (shown below, at left) and Patricia Putt to the test. Whitton and Putt volunteered to provide psychic “readings” for five women (Goldsmiths, University of London, 2012). The entire test was conducted in silence. As you can see here, the women were separated by a screen from the psychics, who recorded their readings as written notes specific to each individual woman. The women were then asked to identify their own readings from among the five that Putt and Whitton had written. Although the psychics called the test “very fair and simple,” they both failed it. For Whitton, only one woman correctly guessed which reading described her—exactly what you’d expect by chance. And for Putt, not one woman guessed correctly.

3.4.3 A Pro-ESP Meta-Analysis

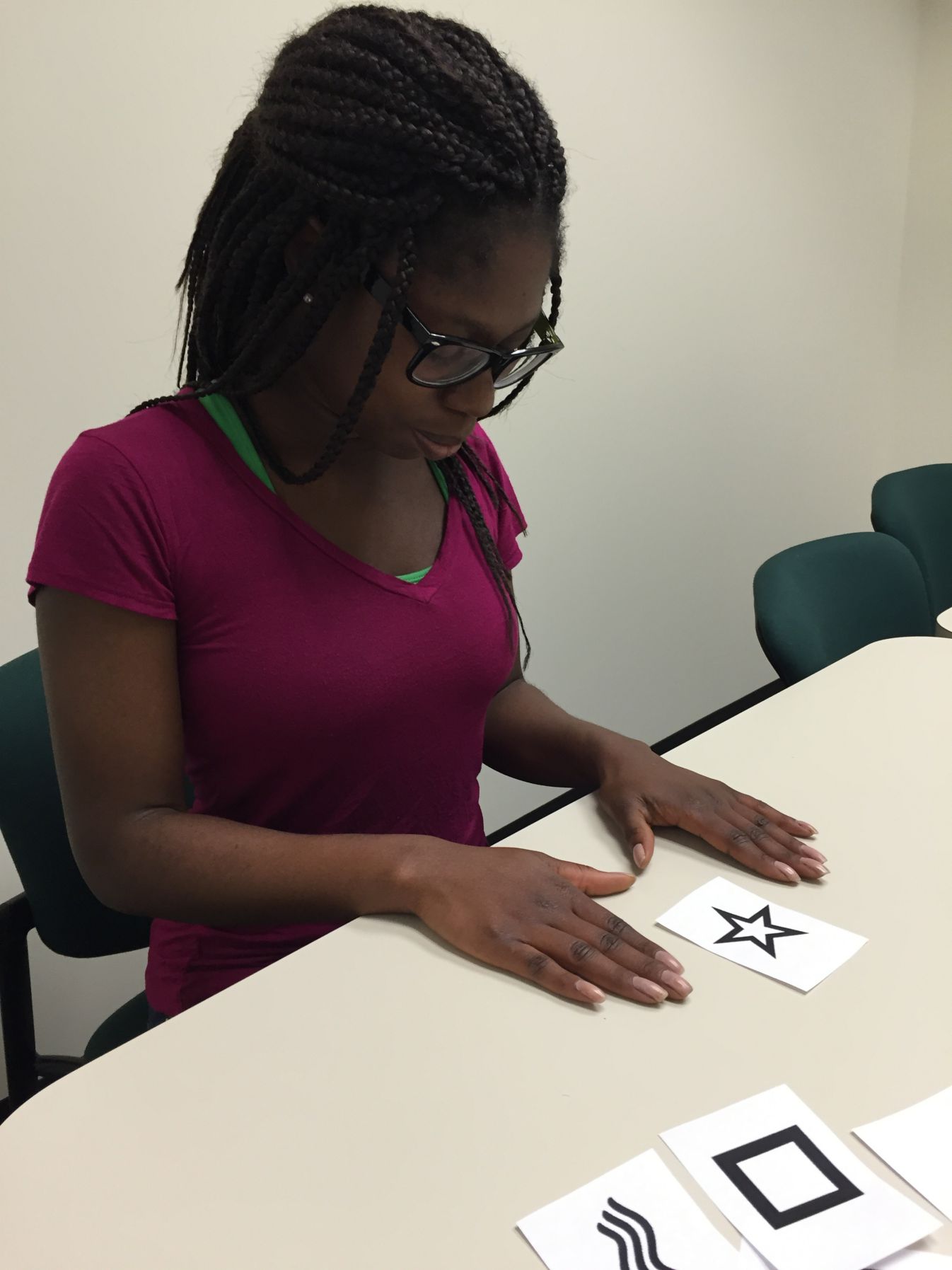

Only a few psychology researchers study ESP. Researchers at the University of London regularly conduct experiments like the one just described, but have never found any support for claims about the existence of ESP. However, in a meta-analysis of 67 different studies, Australian psychologist Lance Storm and colleagues (2010) did find statistical support for the existence of ESP. In some of the studies that Storm and his colleagues examined, a “sender” was asked to telepathically broadcast information about an item to a “receiver” in a separate room. The “receiver” then attempted to choose that item from among a limited number of options.

The researchers did not explain how psychic abilities might work, usually an important part of a scientific write-up. And ESP cannot be explained by widely accepted principles of physics (Rouder & others, 2013). Nevertheless, findings from this meta-analysis (2010) provide evidence capable of convincing a skeptical but open-minded reader that ESP is real.

3.4.4 A Rebuttal Meta-Analysis

A few years later, U.S. psychologist Jeffrey Rouder and his colleagues performed their own meta-analysis, re-examining Storm and colleagues’ findings (2013). Focusing on studies that provided the most support for the existence of ESP, they found errors in many of them. Some studies, for example, did not use proper randomization procedures.

Ideally, researchers prevent any possibility of human interference—whether conscious or unconscious—by using a computer to determine relevant aspects of their experiment. For example, a computer can be used to randomly assign participants to groups or determine the order in which participants view items. However, in some studies included in the Storm team’s meta-analysis, researchers themselves made some decisions about the inclusion or order of items to be shown to the “sender.” Once human judgment enters the picture, the experiment is not truly random; there may be some pattern that is created, even unconsciously, that could change the results of a study.

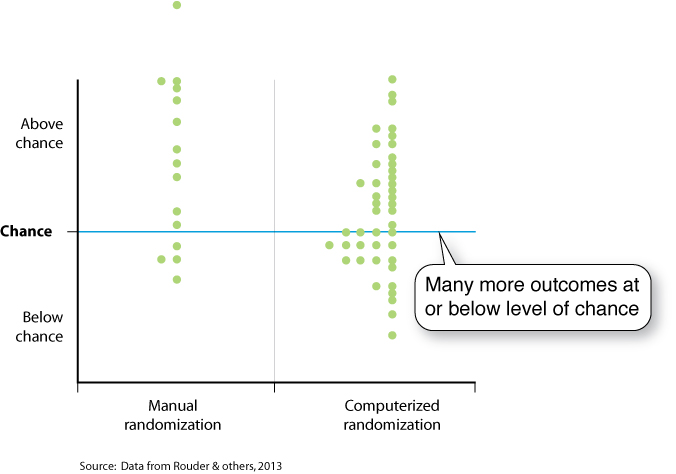

3.4.5 The Effects of Randomization

Do you think it mattered that some studies used full randomization and others did not? Rouder and his colleagues compared these two different types of studies. They found that the experiments that used full computerized randomization showed many more results at or below the level of chance than the ones that did not use full computerized randomization. You can see this difference in the graph. When an outcome is at or below the level of chance, it does not provide support for the experiment’s hypothesis—in this case, the existence of ESP. So these studies provided less support for the existence of ESP than a meta-analysis including studies that used a manual randomization process.

3.4.6 Study Choice in Meta-Analysis

Once scientists track down all of the research in a particular area, how do they choose which studies to include in a meta-analysis? They can’t just flip a coin. A good scientist comes up with careful guidelines and only uses studies that meet those guidelines.

Rouder and his colleagues questioned the selection process for the studies that Storm and his colleagues included in their meta-analysis. Rouder’s team cited examples of studies that they believed should not have been included, as well as ones they believed should have been included. In one case, a research team conducted two experiments that both seemed to meet the criteria to be included in the meta-analysis. Yet, Storm’s team only included one of them—the one that provided more support for the existence of psychic abilities. And this is just an examination of the published studies. What about the ones that have never seen the light of day?

3.4.7 The Missing Research

It is well known that research that finds an effect—say, that ESP works or that there is a difference between two groups—is more likely to be published. Even editors of academic journals and of news sources like magazines are swayed by the excitement of a statistically significant finding. Imagine you are an editor considering which articles to include in the next issue of your popular magazine. In each pair, indicate which fictional headline draws your attention.

Question

DSVxk085Mq1rsE6NMQypU9hX4s8eA0DQCe7dBzIDqqYyufIt7cztJuOpj/RrbrBZEKRLRFhwcfH2Phdumg/CRWh+ZYMGscD8kTn7M32lpoEQlxFePbnYMs4Cxnmnfuvzm63bBPXDA3YnKb4PCApuc8AWxHauOBTRneC7WIegpkcRNWuXGG1tbWC/gkkFtQrxItlCSYzJzv6oAJi/nYI+9jXMBy6fB8q+9LbyWhVuHP6E7+u1koD2l3mt6o9A1WfZC8AOvtx2zHrGvf9WPdAkceu9z/59hcqUOl8zlXZrl5jY8Iu5qIll/3mH/qYQvHKOhGVMV2y//FP6nc1D Vs4PmGHBrSGC5OUpgvhKzCWaec2MjsyKz6bKoCf5KmTa1CpCPWuO1QDzxBiJl5+e5QaaxwkPE5N7OMxFPKrEkV786drwU7WWcDoZY82mwZ8j79ak0PVLqWKPhksAQyvpImHhT1iCIJNOswpLKiRNACDHXJpW6syHBKTWKVjBUWcEyp0qBbnSlidjE81Ts9l4i8tI1z/p3OHx3fcPjUVZAXpScHuIDZBOENN0EThbe4mLavHtSo4jcX4754lLCOxzdwSdUDMK1H7hjJLfQ6q3IJtJitDvCjamUsDsh6iocUrUvmfiusLizF+p9Sv0XI90rCJipK1BhwYQj5IpqmyIuSOMwxgfJkve8KSeLNj1871eiicblf2TOZap6yDUuTQ5f6M8C9cGbrBNuIEg 5I1WQ0wE9NsnueZvZUoqQxIrzQIBGPiVxF/7fnDqlMhlWAXhY07+mYPWeI/J/QT0e4wj06AqK0k74GVG/2A6EPGCeZQUuokvBT32yYUDKtvYN/oqr8uuTBZkDn1Qq2FJ/VVIH2dXzkuAA+SiyymUOSG13hzd17lryg9Bbs9KEJFb3Gza8OPFRTxDHZ8O/SEtLBqVSoARcMGXHB98INDVHqYhOxtBPfGSSlBC4pvPhnVeLUjkjJMprAice6YRYRS8Ywj+WanxF8EyVL/ktsWCChob8ircoP9NI582H1OPUGZ0tszRrkGjb4PP5Nqcz1ZeVBofs/h1ztI=Are experiments that failed to find evidence for the existence of ESP less likely to be published? This common issue is known as the "file-drawer problem" because studies without statistically significant findings are often filed away, never to be seen by other scientists. Rouder’s team points out that the addition of even a few such studies to a meta-analysis would drastically change its conclusion.

3.4.8 So Has ESP Been Debunked?

The way that research studies work is that they either: 1) provide evidence for something, as Storm’s team did with respect to ESP, or 2) fail to find evidence for something, as Rouder’s team did with respect to ESP. What this means is that Rouder’s team’s findings don’t allow us to say definitively that ESP doesn’t exist. However, their meta-analysis does show that the evidence favoring ESP is far weaker than Storm’s team claimed.

Rouder’s team concluded that the Storm team’s meta-analysis is “certainly not sufficient to sway an appropriately skeptical reader” (2013).

3.5 Consider Alternative Explanations

3.

Consider Alternative Explanations

3.5.1 Do You Believe the Evidence Favoring ESP Is Still Compelling?

So, we now have a finding and what we might call a “non-finding”—study results that do not show support. How do you interpret the evidence? Your position in this “debate”—or even your thoughts on whether a debate really exists at all—may have something to do with your response to the quiz you completed earlier in this activity. After you took the quiz, you were asked what you thought the quiz could tell us. You said:

[Student answer]

Most people have prior beliefs about the existence of ESP—they either believe it is possible or they believe it is impossible. Your beliefs likely guided whether you thought the quiz could tell you something or you just thought it was a gimmick.

3.5.2 The Power of Prior Positive Belief

If on the quiz you were open to the belief that you might have psychic powers, it is more likely that the Storm team’s meta-analysis results will remain compelling to you. It can be challenging to respond objectively to evidence that conflicts with our personal beliefs. Remember the psychics who were tested in the British study we discussed earlier? They interpreted the outcome of that test—their failure to show psychic abilities—in light of their own prior beliefs. After the test, psychic Kim Whitton said, “I know what I do is very real, it's easy for me. I'm glad one of the [women] could recognise so many details about herself” (Goldsmiths, University of London, 2012). Remember, one out of five guessing her reading correctly is exactly what you’d expect by chance. That’s like rolling a die repeatedly, focusing on the single time you roll a six, and saying “See how good I am at rolling a six?” But Whitton was not swayed by this evidence.

3.5.3 The Power of Prior Negative Belief

But what if you were skeptical of what it meant to score a five or higher on the quiz you took earlier? Did you recognize that some items on the quiz are linked to explainable phenomena like déjà vu or coincidence? If so, then you will likely also accept that this weakened support serves to discount the existence of ESP. For the half of all Americans who don’t believe in ESP, the results from Rouder and colleagues (2013) suggest that some form of systematic error may be at the root of studies purporting to show ESP.

3.6 Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4.

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

3.6.1 Science and Skepticism

Thinking like a scientist also involves thoughtful consideration of the source of information. In this case both sources are excellent—peer-reviewed articles published in scholarly journals. This means that both Storm’s team (2010) and Rouder’s (2013) permitted their research to be reviewed by a panel of their peers prior to publication. Further, both teams published detailed explanations of the methods used and the results obtained rather than simply a summary of their findings. However, even peer-reviewed studies published in premier research journals are not beyond scrutiny.

Earlier we talked about how your prior beliefs affected what you think about scientific research. What about the scientists’ beliefs? Could they have played some role in the outcome of the meta-analyses? For example, Rouder and his colleagues pointed out systematic errors in Storm and colleagues’ meta-analysis. Imagine that Storm and his colleagues were open to the existence of ESP. Might their prior beliefs have unconsciously led to some of the choices they made about which studies to include?

3.6.2 A Challenge

Thinking like a scientist means being aware of your own beliefs and possible biases—whether you’re reading about science or conducting an experiment. Some research suggests that differences in the way we process information may contribute to the development of beliefs, such as our beliefs about ESP (Gray & Gallo, 2016). So it’s even useful to be aware of how you think! Wherever your personal beliefs lie in any scientific debate, it’s always important to think like a scientist to ensure that you weigh equally the findings that support your beliefs as well as the findings that don’t.

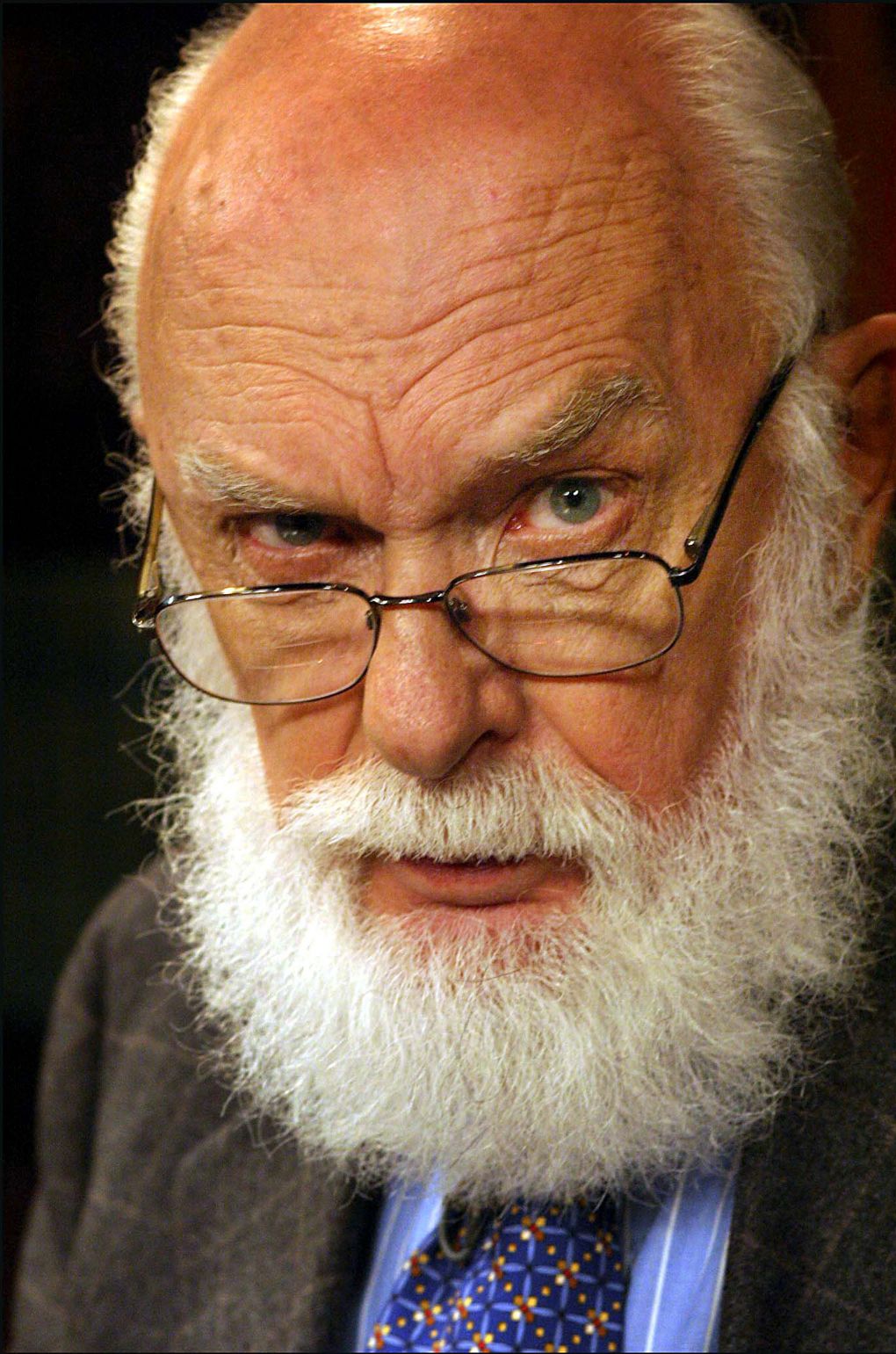

If, after learning about the evidence, you believe you could still have psychic abilities, consider this challenge. James Randi (pictured below), the magician known as “The Amazing Randi” and a self-described “scientific skeptic,” funded, until his retirement, an educational foundation that issued “The Million Dollar Challenge.” If someone had been able to demonstrate psychic abilities, while following the foundation’s scientific protocols, they would have won $1,000,000. No joke! This offer was on the table from 1964 through 2015, and hundreds applied. No one ever won.

3.7 Assessment

5.

Assessment