Chapter 4. Multitasking

4.0.0.0.1 Welcome

Think Like a Scientist

Multitasking

By:

With the assistance of

FAQ

What is Think Like a Scientist?Think Like a Scientist is a digital activity designed to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. Each activity places you in a different, real-world scenario, asking you to think critically about a specific claim. Can instructors track your progress in Think Like a Scientist? Scores from the five-question assessments at the end of each activity can be reported to your instructor. To ensure your privacy while participating in non-assessment features, which can include pseudoscientific quizzes or games, no other student response is saved or reported. How is Think Like a Scientist aligned with the APA Guidelines 2.0? The American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major” provides a set of learning goals for students. Think Like a Scientist addresses several of these goals, although it is specifically designed to develop skills from APA Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking. “Multitasking” covers many outcomes, including:

- Use scientific reasoning to interpret psychological phenomena: Describe common fallacies in thinking that impair accurate outcomes and predictions. [consider overconfidence]

- Use scientific reasoning to interpret psychological phenomena: Use psychology concepts to explain personal experiences and recognize the potential for flaws in behavioral explanations based on simplistic, personal theories. [compare personal belief and scientific findings]

REFERENCES

Finley, Jason R.; Benjamin, Aaron S.; & McCarley, Jason S. (2014). Metacognition of multitasking: How well do we predict the costs of divided attention? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 20, 158–165. doi:10.1037/xap0000010

Gaspar, John G.; Street, Whitney N.; Windsor, Matthew B.; Carbonari, Ronald; Kaczmarski, Henry; Kramer, Arthur F.; & Mathewson, Kyle E. (2014). Providing views of the driving scene to drivers’ conversation partners mitigates cell-phone-related distraction. Psychological Science, 25, 2136–2146. doi:10.1177/0956797614549774

Lipovac, Krsto; Đerić, Miroslav; Tešić, Milan; Andrić, Zoran; & Marić, Bojan. (2017). Mobile phone use while driving-literary review. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 47, 132-142. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2017.04.015

McClurg, Lesley. (2016, October 19). Don't look now! How your devices hurt your productivity. NPR. Retrieved from: http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/10/19/498450445/dont-look-now-how-your-devices-hurt-your-productivity

Ophir, Eyal; Nass, Clifford; & Wagner, Anthony D. (2009). Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 106, 15583–15587. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903620106

Sanbonmatsu, David M.; Strayer, David. L.; Medeiros-Ward, Nathan; & Watson, Jason M. (2013). Who multitasks and why? Multitasking ability, perceived multitasking ability, impulsivity, and sensation seeking. PLOS ONE, 8, e54402. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054402

Schroeder, Paul; Meyers, Mikelyn; & Kostyniuk, Lidia. (2013, April). National survey on distracted driving attitudes and behaviors – 2012. (Report No. DOT HS 811 729). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Strayer, David L.; Watson, Jason M.; & Drews, Frank A. (2011). Cognitive distraction while multitasking in the automobile. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 54, 29–54. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385527-5.00002-4

Watson, Jason M., & Strayer, David L. (2010). Supertaskers: Profiles in extraordinary multitasking ability. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 17, 479–485. doi:10.3758/PBR.17.4.47

4.1 Introduction

This activity invites you to test the claim that many people are good at multitasking. First, you’ll get a chance to see how well you can multitask. You’ll then examine recent studies about whether most people are actually good at multitasking. Next, you’ll explore alternative explanations for why people believe they can multitask well. Finally, you’ll consider the source of our belief that we’re good at multitasking.

4.2 Identify the Claim

1.

Identify the Claim

4.2.1 Do You Multitask?

Do you ever try to do more than one thing at the same time? Are you good at it? It’s possible you’re multitasking right now. Do you have other applications open on your computer? About 70 percent of people think they are better than the typical person at multitasking (Sanbonmatsu, 2013).

4.2.2 Multitasking While Driving

One particular type of multitasking has been in the news quite a bit lately—multitasking behind the wheel. Do you dial and drive? Or text and drive? A recent National Highway Traffic Safety Administration report found that approximately half of U.S. drivers operate their vehicle while distracted (Schroeder & others, 2013). At least some of the time, drivers eat, talk on the phone, text, or read while driving. Twenty percent of people have even applied makeup or shaved behind the wheel!

Most distracted drivers believe they can multitask safely, and there are no statewide bans on most of these activities. Yet, most states do prohibit texting while driving, and several require the use of a hands-free device for talking on a cell phone while driving. It seems plausible that people can safely use a hands-free device to talk on a cell phone while driving, but is this true? Are we good at some kinds of multitasking?

4.2.3 Identify the Claim

We’ve talked about what most of us think about multitasking generally, and about multitasking behind the wheel. Before moving on to evaluating the evidence about multitasking, let’s identify the claim we’ve been discussing.

Question 1.

4.3 Evaluate the Evidence

2.

Evaluate the Evidence

4.3.1 Test Your Multitasking Skills

Let’s see how good you are at multitasking. In this activity, you will complete two tasks. The first task requires you to listen to a story and respond to the words “left” and “right” as you hear them. The second task involves exchanging text messages with another person. You’ll first attempt each task individually. Then, after you’ve tried each task, you’ll attempt both tasks at the same time. Neither task is particularly difficult, but doing both at the same time will require you to switch your attention back and forth between the two tasks.

4.3.2 Left or Right with the Wrights

In this task, listen carefully to “The Wright Family Story.” Each time you hear the word “left,” press the left arrow key on your keyboard (or select the left button on the screen). Each time you hear the word “right” or “Wright,” press the right arrow key on your keyboard (or select the right button on the screen). In order for your response to be correct, it must be entered within 1 second of hearing “left” or “right” or “Wright.” To open text line press down arrow key on your keyboard.

To work with this widget, we recommend you to connect the keyboard.

Question

4.3.3 The Texting Activity

This next activity simulates texting. Like normal texting, incoming messages will appear on the cell phone screen. You will use your keyboard to respond. The response you need to type will appear in red above the cell phone’s text window. Type that exact message in the text box using your keyboard and then select the word “Send.” You’ll receive one point for each message you send where all the words are spelled, capitalized, and punctuated exactly like the message in red.

Question

4.3.4 Time to Multitask

Did you find the left/right task or the texting task challenging? You probably didn’t, but now try doing them both at the same time. Remember, you can use the left and right arrow keys or the left and right buttons on the screen, whichever is easier for you. To open text line press down arrow key on your keyboard.

To work with this widget, we recommend you to connect the keyboard.

But you can do texting task at first and then audio task by pressing F2. If you want to skip this activity press F4.

Question

4.3.5 How Good Were You at Multitasking?

So how did you do at multitasking? Were you surprised at your score when you did both tasks at the same time?

Question 2.

4.3.6 Multitasking Rates

Let’s look at some general research findings about multitasking and then explore one study in more detail. [] Researchers estimate that just over 97% of people perform worse when multitasking than when just doing one task at a time (Watson & Strayer, 2010). Just 2.5% of us are good at multitasking.

4.3.7 The Equivalent to Being Legally Drunk

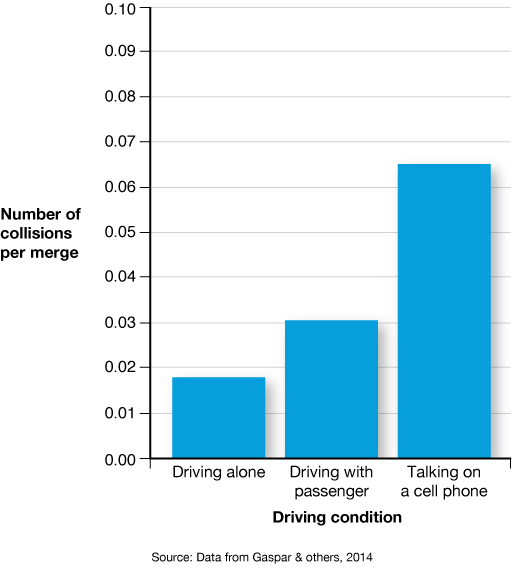

Although we’re not good at it, many people engage in multitasking. We even multitask in situations where focused attention is crucial for safety, such as when driving. How dangerous is this? In one study, researchers reported that carrying on a conversation while operating a driving simulator resulted in driving impairment equivalent to being legally drunk (Strayer & others, 2011). This effect has been demonstrated even for participants using hands-free devices (Lipovac & others, 2017). Another study showed that talking on a cell phone while merging into traffic increased the rate of accidents (Gaspar & others, 2014). Talking on a cell phone also led to more accidents while merging than simply talking with a passenger.

4.3.8 Studying Multitasking

What about multitasking in other situations? If you’re not risking a car crash, can multitasking be helpful? In order to explore the effects of multitasking, researchers compared people who multitask a lot with people who rarely multitask (Ophir & others, 2009). These two groups were determined by asking people about their behavior when “consuming media.” A “heavy multitasker” could be someone who uses multiple devices at once, for example, watching TV while listening to music and looking at information online.

Question 3.

4.3.9 The Effects of Multitasking

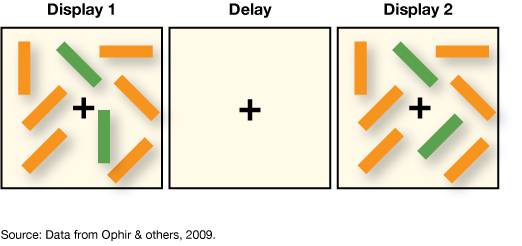

The researchers asked both the light multitaskers and the heavy multitaskers to complete several cognitive tasks, including the one shown here. Participants see one display flashed very briefly. It’s then removed for about a second before a second version of the display is shown. The task is to identify whether either of the green bars has changed its orientation, while ignoring the orange bars, which are distractions. In the figure here, for example, the green bar on the bottom shifted from vertical to diagonal.

Question 4.

4.3.10 Multitasking and Cognition

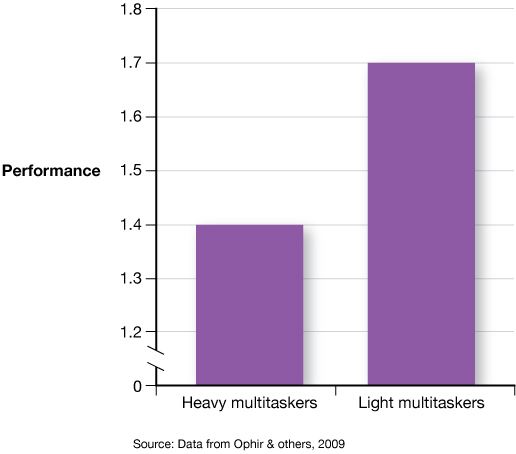

You guessed the multitaskers would perform better on this task. As you can see in this graph, on average, the light multitaskers were better at tuning out the distraction of the six orange bars than the heavy multitaskers were. The researchers believe this finding suggests that heavy multitasking makes it harder to tune out distracting information. That is, multitasking impairs some cognitive abilities. Other research echoes these findings, concluding that people “who chronically multitask are not those who are the most capable of multi-tasking effectively” (Sanbonmatsu & others, 2013).

Earlier you said that you were more of a multitasker. Does this finding affect how you think about your own habits?

4.4 Consider Alternative Explanations

3.

Consider Alternative Explanations

4.4.1 Overconfidence

All the research points to the fact that most people can’t multitask effectively. Why not? Multitasking involves the division of attention—and attention is a limited resource. When you try to pay attention to more than one task at the same time, your performance on both tasks suffers (Finley & others, 2014). [] In fact, in terms of probability, there is only a 1 in 40 chance that any individual person can actually multitask effectively.

So why do most people think they are good multitaskers? One reason is that people are often overconfident about many of their abilities. Multitasking is just one area in which people are overconfident (Sanbonmatsu & others, 2013). More than 70% of college students believe they are above average at multitasking. Unfortunately, this confidence is usually misplaced.

Question

FXaG6YykEjpaTwGyI9wgwRg1X+12+lEv4MSGPoTv9cQLp5TXmX9xOI65xB6Zia/w38dkH9Z3Xqkf9hQMQ1v6XaGe8ZEUGu0hr19mFLchNsJAu4dMlNDw3PIvqNiMDIXfvBH9+b76CM2+wKPzP8fwwVxAGE3Vk4ISctSz8OmHUiDDetIwEjENSynPp5dNqNHuI469Fiy7vLpVFa31n25d1HqvTiOz6oe2sW8TvZJpBI4slBg4FCbhLVO0kUyuedp2Ov1y/LH3zLbnistIgWrWyDj79caCBOOEQEdUvbleBMd45sD7gDKkt3LlKTismhCQ+ch4iQ==4.4.2 Inattentional Blindness

Here’s another explanation for why most people think they can multitask: They don’t know what they’re missing. If we don’t notice when we miss things, we don’t realize that we’re making mistakes. This likely leads to some of our overconfidence. Maybe you didn’t notice walking past your best friend because you were too busy checking Instagram. Or maybe you didn’t notice that you missed the light turn red because you were texting. As you learned in the chapter on consciousness, this obliviousness is called inattentional blindness. It occurs when our attention is drawn to one task, and we fail to notice important events that are clearly in our field of vision.

4.5 Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4.

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4.5.1 Personal Beliefs vs. Scientific Findings

The claim we have been considering is that most people are good multitaskers. However, it turns out that very few people can multitask well, and those who multitask a lot can experience negative consequences.

So where does the claim come from? In this case, the source of the claim is likely our personal beliefs. However, thinking like a scientist means that we need to set aside our personal beliefs when they don’t agree with scientific findings. Ignoring the scientific research and being overconfident in our ability to multitask can put our lives at risk and impair some of our cognitive abilities.

4.5.2 When Nearly Everyone Believes They Are Part of the Special 2.5%

Unfortunately, many people don’t understand how difficult it is for the human brain to switch between two different tasks. Too many people think they are part of the special 2.5% who can multitask effectively. Distracted drivers rarely notice how dangerously they are driving as they also attend to something other than driving. As this video shows, people shouldn’t even text while doing something as simple as riding an escalator!

4.5.3 The Myth of Multitasking

For almost everybody, the ability to multitask is a myth. Based on the research, neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley offers advice for when you really need to get work done (McClurg, 2016). Get rid of any noise you can. Clear everything from your workspace. Use one screen, one browser, and one tab. Turn off your phone, your email, and any other alerts.

Earlier, you wrote about an example of multitasking in your daily life, as well as how the research on multitasking has made you think about your current behavior. You said:

New Paragraph

For most of us, multitasking might be wasting hours of productivity every day. The example you provided might be a good place to begin breaking the habit of trying to multitask, perhaps using Gazzaley’s advice.

4.6 Assessment

5.

Assessment