Chapter 6. Eyewitness Testimony

6.1 Welcome

Think Like a Scientist

Eyewitness Testimony

By:

FAQ

What is Think Like a Scientist?

Think Like a Scientist is a digital activity designed to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. Each activity places you in a different, real-world scenario, asking you to think critically about a specific claim.

Can instructors track your progress in Think Like a Scientist?

Scores from the five-question assessments at the end of each activity can be reported to your instructor. To ensure your privacy while participating in non-assessment features, which can include pseudoscientific quizzes or games, no other student response is saved or reported.

How is Think Like a Scientist aligned with the APA Guidelines 2.0?

The American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major” provides a set of learning goals for students. Think Like a Scientist addresses several of these goals, although it is specifically designed to develop skills from APA Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking.

“Eyewitness Testimony” covers many outcomes, including:

- Interpret, design, and conduct basic psychological research: Define and explain the purpose of key research concepts that characterize psychological research [identify independent and dependent variables in a study]

- Demonstrate psychology information literacy: Describe what kinds of additional information beyond personal experience are acceptable in developing behavioral explanations [compare the legal system and psychological science as sources of information about eyewitness identification]

REFERENCES

Innocence Project. (n.d.). Eyewitness misidentification. Retrieved from https://www.innocenceproject.org/causes/eyewitness-misidentification/

The Justice Project. (2007). Eyewitness identification: A policy review. Retrieved from https://public.psych.iastate.edu/glwells/The_Justice%20Project_Eyewitness_Identification_%20A_Policy_Review.pdf

Klasen-Kelly, Fred. (2017, June 13). 7 people saw the same shooting. But on some details, they couldn’t disagree more. The Charlotte Observer. http://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/article155845954.html

Loftus, Elizabeth. (2013). 25 years of eyewitness science……finally pays off. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8, 556-557. doi:10.1177/1745691613500995

Megreya, Ahmed M., & Burton, A. Mike. (2008). Matching faces to photographs: Poor performance in eyewitness memory (without the memory). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 14, 364-372. doi:10.1037/a0013464

Pickrell, Jacqueline E.; McDonald, Dawn-Leigh; Bernstein, Daniel M.; & Loftus, Elizabeth F. (2017). Misinformation effect. Cognitive Illusions: Intriguing Phenomena in Judgement, Thinking and Memory, 406-423.

Wan, Lulu; Crookes, Kate; Dawel, Amy; Pidcock, Madeleine; Hall, Ashleigh; & McKone, Elinor. (2017). Face-blind for other-race faces: Individual differences in other-race recognition impairments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146, 102-122. doi:10.1037/xge0000249

Watkins v. Souders, 449 U.S. 341, 352 (1982) (Brennan, J. dissenting).

Wells, Gary L., & Olson, Elizabeth A. (2001). The other-race effect in eyewitness identification: What do we do about it? Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 7, 230-246.

Wixted, John T., & Wells, Gary L. (2017). The relationship between eyewitness confidence and identification accuracy: A new synthesis. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 18, 10-65. doi:10.1177/1529100616686966

6.2 Introduction

This activity invites you to test the claim that eyewitness testimony is typically accurate in identifying perpetrators of crimes. First, you’ll get a chance to be the eyewitness to a crime. You will then consider the accuracy of eyewitness identification and testimony. Next, you’ll consider an alternative explanation for problems with eyewitness identification. Finally, you’ll compare the legal system and psychological science as sources for information about eyewitness identification.

6.3 Identify the Claim

1.

Identify the Claim

6.3.1 Are You a Good Eyewitness?

Eyewitness testimony is widely used in criminal court cases, in large part because most cases don’t have biological evidence such as DNA (The Justice Project, 2007). And it works—that is, it helps to convict people. In the words of the now-deceased Supreme Court Justice William Brennan, “there is almost nothing more convincing [to a jury] than a live human being who takes the stand, points a finger at the defendant, and says ’That's the one!’” (Brennan, 1982).

But just because eyewitness testimony is convincing doesn’t mean it’s accurate. Thinking like a scientist involves asking good questions. Just how accurate is eyewitness testimony? If you witnessed a crime, do you think you could later identify the perpetrator? Let’s try it. Watch the video clip here. It begins with a group of 10 volunteers partway through a day of tests they were taking for a TV documentary.

6.3.2 Who Did It?

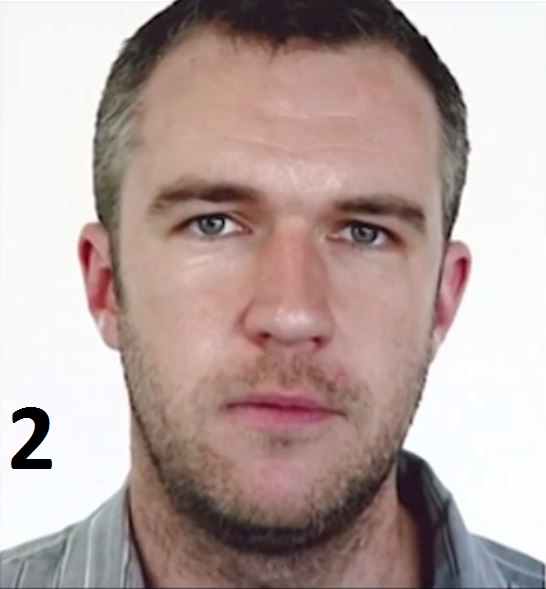

You were just an eyewitness to a crime. Can you ID the person who committed the murder? Look closely at the ten photos shown here.

Question

jKyHzXeZB+EFHvaoPK3ZXG7ShNfoO8WWe9NKF6GKHefM6IF8WTmbk3C+vZpMEUYhV8Bb2cwPr8Kv2sGQmT9GbZU8y/joKV92wMq3Ej5Tf5CDgjMk/86bpPudcIbDFxxllfIolHkbIUxzXZl7Pr53YaOMCvckoj08AzRkH8919CwvVsTfXuXWmgxgI0hFdtvZOMPHhhjxH4/tcscrB8YOHBwG561FtucmH0Q66KdIpegwhqMpK9W6AZUmldbpGImyLCPEGKM9tMVdf5TDWe’ll come back to the suspect you ID’d later in this activity, so you can see if you’re right.

6.3.3 Identify the Claim

Consider the discussion of eyewitness identification so far, as well as the video you just watched.

Question 1.

Nmm4qXBsHeDxMXil22EMj+7Aq9mMunpODwr37CZ3P3o4cXP0cgKYKNMF2MqWTbFT1Pf1EFhnSJicsE6YN6+oWmFcQ4IggSc2/lZWwEYM1VrgA0KNON9laDyLCLIjW9/SW/JRuNAoqnk0Xp09vRAXcZovRxUR+Av0jL5bBNfq227Dl80Um1L/Xwt3zY122xRhTnDVExsWU/J8JKEp7lY1XyzeliXaiu7VliT00ndXBppZjdhaIBYBsXhQwWw/oZExfdOSS1Rr1QWzh3saV2O2k+4jPWvpiCqFbGjzYPU+ShSZ9hRo2qB4eToUqJXcCBqoGk23/+NspmaNBDKd/YA1H4ryKg36xVuKpLfHNWJyRm1DdMrZKXatmpQXjcr/jCgAWN60Xm97VJMq82oIZTMtwH32CCUCyHsUS+3PQ5UyEXrw9jn/mHuOBPlizAJuhjAq5depLpByxjBNIvC9SoiHk8S5Iu4ZzgTaSLw+LLy4j37Lbqa3vYrw/CBRrvJkU47fq5CWO2dL35yi0+d2KsGl4xEhwc4/nQju7GcVi88zRgYeRjt1qw5HiqjfNq2JgH5coF4LI0gKLqgtiDUU0NwKpFNhBLZkXir4LxOKcZiN4+UEnLq1i1ND5Ia4C5mB6+Jx051rfyir99oD3NpDwzlRxLRBgAmb0LOvKWaOsZZG0O6TXuHbytJyq8yCKECDJ51jgC2wRMG55af5LZN76RN+MXn7MyUJ8Z6+1De6FR8SZs1JAny9rUbyHa65g9yjW1PBjdbWLn5RjA2m6D+zZuJW/tThTnsApONpctlqLUoQ97XfZTeZM4AnGw==6.4 Evaluate the Evidence

2.

Evaluate the Evidence

6.4.1 Testing the Claim

[]

Remember, there was a group of volunteers in the pub watching the same fatal stabbing that you saw on the video. Let’s see how they did!

So, none of the live witnesses picked the actual murderer! And one of them even placed him in the pub at the time of the murder.

6.4.2 Misidentification

Were you surprised at how poorly people, as a group, tend to do at identifying a suspect? It’s likely that, overall, the students in your class are doing just as poorly as the volunteers in the pub. More than 100 introductory psychology students watched the same video you did, and just 10.2% of them chose the correct suspect – suspect number 1. That is exactly what would happen if they just guessed with their eyes closed! About 20% chose suspect 2 who wasn’t even in the pub at the time of the murder. And about another 20% chose suspect 8 – the victim! Based on these results, the police might have arrested the wrong suspect.

6.4.3 When We Misidentify

Just by chance, about 10% of people doing this activity will be correct and the remaining 90% will be wrong. Surprisingly, most people don’t do much better than chance at identifying the correct perpetrator. The majority of viewers will misidentify the murderer, as did the introductory psychology students and most of the witnesses (who saw it live). What’s scary is that, in real life, this eyewitness evidence could be used to convict a suspect, even if he or she is innocent. Remember, in the video clip you watched earlier, two of the witnesses picked suspect 2 (as did about 20% of the introductory psychology students), and suspect 2 wasn’t even present at the crime!

6.4.4 Unreliable Identification

Why aren’t people much better than chance, or just guessing, when they identify a suspect that they saw briefly? The hypothesis—that eyewitness identification is typically accurate—has been tested many times by psychology researchers. This is a case where the verdict is clear: Eyewitness identification is notoriously unreliable (Loftus, 2013). We know this because of cases in which eyewitnesses give markedly different accounts. In one instance, eyewitnesses reported different races for two men involved in a fight, and they differed on which of the two men started it (Clasen-Kelly, 2017).

Some eyewitness reports have even been contradicted by scientific evidence! More than 300 people who had been convicted based on eyewitness testimony were later found innocent based on DNA evidence (Innocence Project, n.d.). As just one example, Larry Fuller (pictured below) was identified as a rapist by an eyewitness. Fuller had a full beard, and the eyewitness originally said that the rapist had no facial hair (Justice Project, 2007). You can’t grow a full beard in a matter of hours or days! Still, this eyewitness identification was used to convict Fuller. In 2006, after 18 years in prison, Fuller was finally exonerated and released based on DNA evidence.

6.4.5 Why We Misidentify

Why is eyewitness identification so unreliable? Let’s look at the psychological research. Much research shows that eyewitness misidentification results from memory problems (Loftus, 2013). For example, researchers have studied how the misinformation effect—being exposed to misleading information after an event—can affect an eyewitness’ memory (Pickrell & others, 2017). Researchers have also examined the influence of racial bias on memory accuracy. More specifically, people tend to misidentify people of other races more than people of their own race (Wells & Olsen, 2001; Wan & others, 2017).

So memory is a problem for eyewitness identification. But is it the only problem? Thinking like a scientist means looking for alternative explanations. What else besides memory is involved in eyewitness identification?

6.5 Consider Alternative Explanations

3.

Consider Alternative Explanations

6.5.1 Identifying Faces, Part I

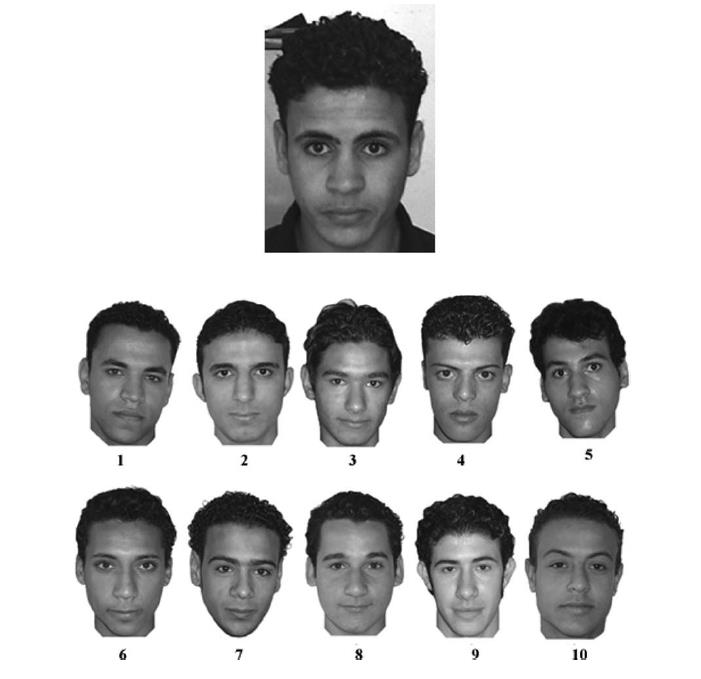

Although memory surely plays an important role in misidentification, some researchers have focused on our initial observation of a crime, asking how well we encode information about people’s faces in the first place. In one study, researchers tested participants’ ability to accurately identify someone without any time lag (Megreya & Burton, 2008). As the researchers put it, they wanted to test “eyewitness memory (without the memory).” By removing the impact of time and memory on the identification, they sought a baseline of the absolute best that people could do with eyewitness identification.

The researchers showed their participants a man and asked them to identify the man within an array of ten photos. Participants performed the task multiple times, trying to match images of a different man each time. Half of the time, the array included a photo of the man. Half of the time, the man was not in the photo array at all. Try it for yourself. Look at the man in the top photo here. He may or may not be in the array of ten photos below it. Below the photo array, click the number of the photo that matches him, or the option that says, “He’s not here.”

Question 2.

mT0p2bJqiXXxweIdgoIXA6uFH9/H63hNpOXq72gQ2bS28VS4zXt9LuET9RSAyqmxCxQHsJL3PxPnURta3X+DkUsQQOxXX2f75dlyDnLGz3ZjG6PGMceqHZYMQOlJkcUE9WL0KHC+v/GvOY0cvCwBg5K6SM545m2JqYiFtPvYJZ43mRcQ3gU48eqHUxblMgStTGDLFUJctourQ1DCAlldEDwUIclXwzimOqiXX76YjMCYj6sElpAn9QWniXlgnfm6YtQAWMPmiBXALTDiVHH/F+Qw88zKoSamneLOww9DZACiAR8UwcoO8eD0SScuSKwl5bsVQQvnOvaqcphGaDBgyNr8j6OMRquGG0LH6gcNkAT/YXyiE594JmAM1hkGTnBO+4f5bPNwszXxEpOOab2DyxSnn1o7XlrrNwnTnniao8G9sGmZ4BYFLo1wZjL/fJLFIFDcEa4OKfckO3Ud5+e8FfZtnkBx7HIiXnB+JAT/1vPUpCpkmB3vy9AKBydS0Bb1CPgVcsHdEiDjE7/lppbzjpEwFtWmcrmZLFXcqtTrhZUSjVBL+h5iJ+T+16/PeSGJTilXmbnPlk+8jcF31sVRvg9gHsjB/c84sCfzPfx2CUeREc0yn3ouHXEIAfVQO1UxhfzZ/xGHXdzj6Vg22BVw8XUcAvR67f3J9eCkxA==6.5.2 Identifying Faces, Part II

Let’s first think about this experiment, and then think about what we predict the outcome to be.

Question 3.

30+Q8sWUM5HxaRZV4hEiQ/KJRM73KfhLHsR4hB2J7PgFgZdL/xXZ2EjRpQ8/QCv1wt95bf2yRIZevryJ8L+g4HsL8jNsqlTEwQ6a7M3hMiTaestGTGu0OY5XM5XDHwl765i5Xjuntw21lX2orawjwCJu7ssM9v9VH1eR6NwXyXxw/KdGPJGV0XtCLK0HkVHa4ohIb3SVrV4a98C7oL5yFDYvScJ6UsLrUzDA1jw/0Zwm2xMouaeuNjdLwsrjBY48Pg4CFDGjwn8ZK3S6Z2RMkBQjfM6WXk/bt6F4lD/YICy3ubk17ssMInYuRq1fq0DYByXp8AIs2TRQ6LSok9/SHMRpObG+S/YAQeraqJspBfKYohxCKrSAyuy+Q1SwMszGRZguPS7XY4yhiVf0SX2remZKKnGTd6THn+mHQxblPziz+izvY125e/zHwyZosZeeSZob8VgBS8rn/5HIrsCO4jl4+s5gW+O5GNn9L9hOZNRACOHq09tggjh/BsjY6xYZULZQWyQqwjk=Question 4.

tDfEO0TYxA4+VIr7yJkfRe5EkAZTZ9lyBvjOUivDOnN6AkX1pa28sM7zP7MISlGdmnE0X++virRYmMPO5E27e0s9TmcFT+P0B7hLT3nOahmZ4LoLh3duqNb476iHe1x+PBBfZoKxgY4Z1tbUXGZ8e0UAEBxcaNg16UaBSPeF2DhsfNyK976yCarGvN1XhaBH9J2gJS0L4qHTwCLeYQ7WkWbkNcD0Lpf941jHGmSG3MatLXO225V1rC7T1WdEuznwh4JXKc0tiXHnIYRWUvqfSeu4wO+qyo5jj3Aii3TPn8fPuHi3xYndlIn2znU0iHJiFjP0L6xuDD5Im1gBh/PEx6fvYKJhlSYSRvtQZiobwvAoA++PTsrPmNBqOYraQkLpghZ9qSygbBvFIawnym4H/ImG0v3xn7dPL/fTxrzoxKwVFMq2BuS06yTtClSlXw8IeNupzz9tNFLltxWQnOOsDw==6.5.3 Recognizing the Suspect, Part I

In the study we’re discussing, participants didn’t even need to hold a face in their memory in order to identify a person later. They simply needed to look back and forth to figure out who the person is, which seems to be an easy task (Megreya & Burton, 2008). [] The researchers ran this easy identification part of the study to provide a baseline for eyewitness recognition. That is, if eyewitness memory is bad, what is the best we can hope for in terms of simply recognizing a suspect?

Question

U/FyMAPJZSg6NgaeSxouikI6KVqmOkoYCD4Q+i2rvEbLrz35dHWZUnSDxuYJs6wtPk70qS+dAdg2e6fj0Oj4+J/ODOXOZNrF/t/MJhXLVNmJ82+0ZqyT8iom7dY+VfgGydzO9AFNP6cGWFkygSqEeA5dMOPLP52gIm7d5UQDGfWluB3jo11wKuDCTwatBY8NLHgZbvK1xO9aUhB0UFUzfZDyPjQcKj/qCQePgTr23okzw+K+n8/hlEyDlznwKvLQvz2jaoWDaeytBB5BzR8olt61a3tZZqO/6.5.4 Recognizing the Suspect, Part II

In the previous screen, you estimated that people would accurately match the target with the correct photo NO RESPONSE ENTERED of the time. In the actual study, even with this apparently simple task, participants were only a little over 66% accurate. Accuracy rates were similar in both conditions—when there was a matching photo below and when there was not. As the researchers put it, “matching images of unfamiliar faces is a difficult task” (Megreya & Burton, 2008). So, rather than set a baseline against which the memory part of eyewitness identification could be judged, these researchers discovered a new problem: Simply encoding the face of the perpetrator isn’t easy!

6.5.5 The Many Stages of Eyewitness Identification

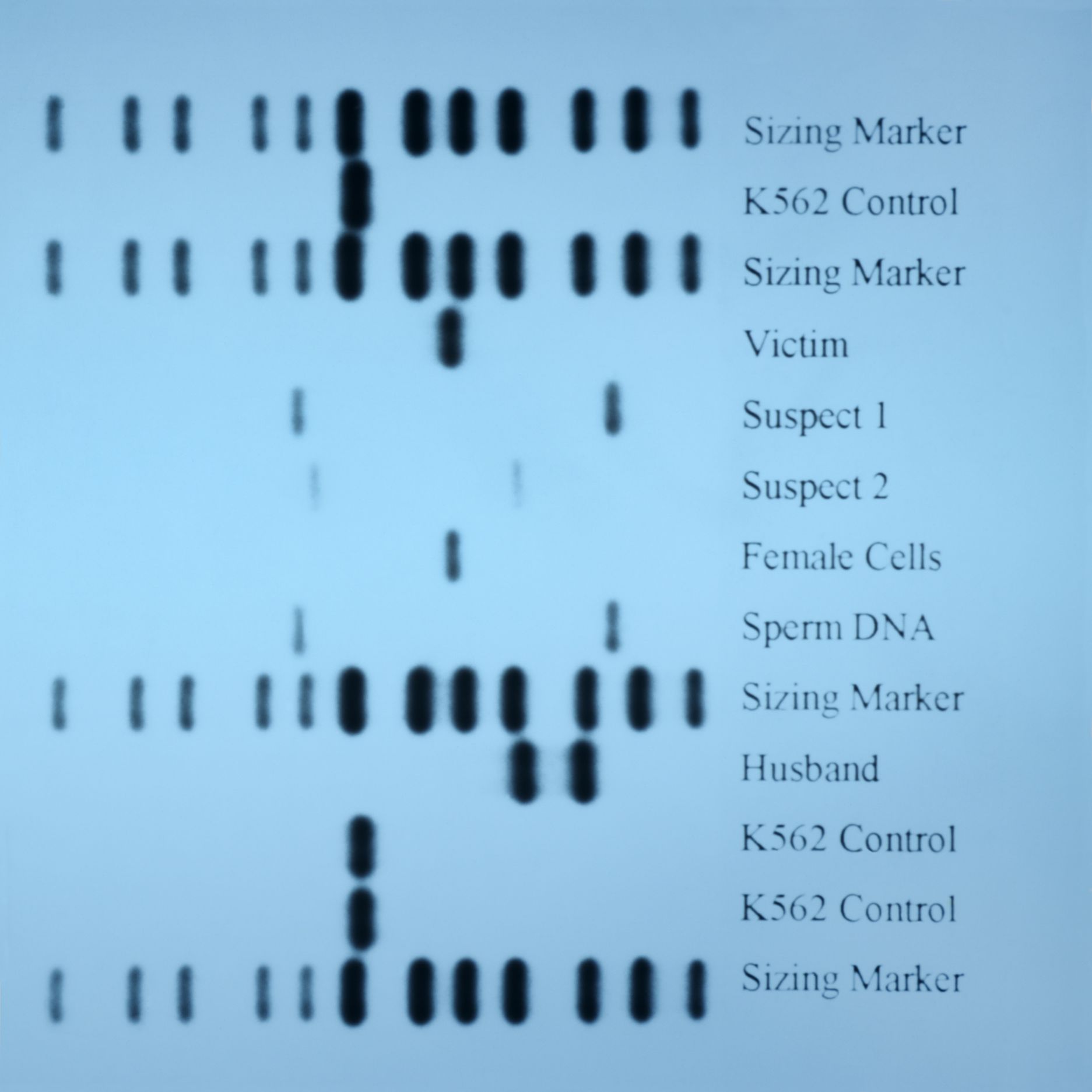

Psychology researchers have demonstrated overwhelmingly and convincingly that eyewitness identification is fraught with the potential for error. DNA testing has confirmed these errors hundreds of times. (An example of a DNA test result is pictured below.)

Identifying a perpetrator is complicated. The first step is simply encoding the details of the person’s face and then picking out the same face in a different context. But as you now know, people get that right less than two-thirds of the time. And accuracy decreases even more when there are other factors involved, such as a time lapse or misinformation, which can alter even a correct memory.

6.5.6 Eyewitness Memory

Based on the discussion within this activity, which of the following are possible reasons for the misidentification? Select all that apply.

Question 5.

6huFohHnI6aqmMKcVLljBNgorvk= The influence of racial bias

6huFohHnI6aqmMKcVLljBNgorvk= Problems encoding the face

6huFohHnI6aqmMKcVLljBNgorvk= The misinformation effect

6.6 Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4.

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

6.6.1 Science vs. Law

The case of eyewitness testimony offers an interesting contrast in sources. Remember the quote from William Brennan (pictured below)? “There is almost nothing more convincing [to a jury] than a live human being who takes the stand, points a finger at the defendant, and says 'That's the one!’” Turns out Brennan said that when making an argument that eyewitness testimony is problematic. In fact, he found eyewitness testimony problematic because it is so convincing, and people don’t realize its flaws. Unfortunately, Brennan is in the minority. For the most part, the legal system has prevented experts on eyewitness testimony from speaking about these problems at trial (Loftus, 2013). To figure out why, let’s examine the two sides—the law and psychological science.

![This is a photo of William Brennan who stated that “There is almost nothing more convincing [to a jury] than a live human being who takes the stand, points a finger at the defendant, and says 'That is the one!’“](asset/ch6/images/TLS6UN8_56481964.jpg)

6.6.2 Psychological Science in the Courtroom

The most famous researcher of eyewitness testimony is Elizabeth Loftus (pictured below). Loftus summarized the history of the relationship among psychology, law, and eyewitness testimony (Loftus, 2013). Before the 1980s, she notes, expert psychologists were barred from sharing research in the courtroom out of fear that it might interfere with the juries’ decisions. The legal system and the general public were skeptical of psychological science as a source. Eventually, several higher courts (including the Supreme Court) started reversing verdicts if an expert on eyewitness testimony was excluded from the trial. The arrival of DNA evidence bolstered these higher court decisions. Three-quarters of cases that have been overturned by new DNA evidence were originally based on eyewitness misidentification.

6.6.3 Psychology and Law Now

Now, psychological research on eyewitness identification is mostly accepted by the court, but there are still misconceptions among the general public (Loftus, 2013). People continue to be convinced by one person pointing the finger at another. To help reduce eyewitness misidentification, the Innocence Project encourages techniques that psychological science has shown will reduce eyewitness misidentification before a jury hears any testimony in court (Loftus, 2013; Wixted & Wells, 2017). The techniques are listed below. See if you can drag-and-drop each technique (in blue) to match it to its correct explanation. After you correctly match each technique to its explanation, you’ll read why each technique was developed.

The law increasingly bases its eyewitness policies on psychological research. Hopefully, information from both sources will convince the general public that eyewitness misidentification is real, but its occurrence can be reduced by the techniques listed here.

6.7 Assessment

5.

Assessment