Chapter 8. Lie Detection

8.1 Welcome

Think Like a Scientist

Lie Detection

By:

FAQ

What is Think Like a Scientist?

Think Like a Scientist is a digital activity designed to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. Each activity places you in a different, real-world scenario, asking you to think critically about a specific claim.

Can instructors track your progress in Think Like a Scientist?

Scores from the five-question assessments at the end of each activity can be reported to your instructor. To ensure your privacy while participating in non-assessment features, which can include pseudoscientific quizzes or games, no other student response is saved or reported.

How is Think Like a Scientist aligned with the APA Guidelines 2.0?

The American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for the Undergraduate

Psychology Major” provides a set of learning goals for students. Think Like a Scientist addresses several of these goals, although it is specifically designed to develop skills from APA Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking.

“Lie Detection” covers many outcomes, including:

- Use scientific reasoning to interpret psychological phenomena: Describe common fallacies in thinking that impair accurate outcomes and predictions. [consider confirmation bias]

- Demonstrate psychology information literacy: Articulate criteria for identifying objective sources of psychology information. [compare journal articles and online ads]

REFERENCES

Bogaard, Glynis; Meijer, Ewout H.; Vrij, Aldert; & Merckelbach, Harald. (2016). Strong, but wrong: Lay people’s and police officers’ beliefs about verbal and nonverbal cues to deception. PLOS ONE, 11(6), doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156615

Bond, Charles F., & DePaulo, Bella M. (2006). Accuracy of deception judgments. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 214–234.

Frank, Mark G., & Feeley, Thomas Hugh. (2003). To catch a liar: Challenges for research in lie detection training. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 31, 58–75. doi:10.1080/00909880305377

Hauch, Valerie; Sporer, Siegfriend L.; Michael, Stephen W.; & Meissner, Christian A. (2016). Does training improve the detection of deception? A meta-analysis. Communication Research, 43, 283-343. doi:10.1177/0093650214534974

Nickerson, Raymond S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2, 175–220.

Porter, Stephen, & ten Brinke, Leanne. (2010). The truth about lies: What works in detecting high‐stakes deception? Legal and Criminological Psychology, 15, 57–75. doi:10.1348/135532509X433151

Smith, Jonathan C. (2010). Pseudoscience and extraordinary claims: A critical thinker’s toolkit. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

8.2 Introduction

This activity invites you to test the claim that lie detection skills can be improved with training. First, you will test your own lie detection skills by guessing which people in a series of videos are lying. You will explore the evidence on how successful people tend to be in detecting lies in everyday life. You will receive instructions that some people have used in efforts to improve their lie detection skills. You will then have another opportunity to test your own lie detection skills. You’ll examine an alternative explanation for your beliefs about your own lie detection abilities. Finally, you will compare two sources of information about lie detection training, online ads and published peer-reviewed journal articles.

8.3 Identify the Claim

1.

Identify the Claim

8.3.1 Who Is Lying?

Wouldn’t you like to know if someone is lying to you? We all know people lie to us at times, but do we know when we’re being lied to? Are these people lying—the person who declines your party invitation because she is too busy, the lab partner who claims he lost his work because his computer crashed, or the salesperson who tells you that the outfit you’re trying on looks fantastic on you?

8.3.2 Lie Detection Training

None of us is a perfect lie detector. If we were, no one would be able to get away with lying! Whether you think you are good or bad at detecting lies, you probably would like to get better at it. Many Web sites offer training programs to improve your lie detection ability. Look at this mock ad, developed from actual Web sites for lie detection programs. (Click image to enlarge.)

Question

pyEZL3hwaFGgDQbNohKyF1M3GB0ZkeOzrQsRdN3UJMpQT2hn5ArKKG2jwGjlQkQnq70wtKua2trS7+uH8I7dY4oQ+VxHMApERzciBCkzuvKii4vCR+74wuOruUg=8.4 Evaluate the Evidence

2.

Evaluate the Evidence

8.4.1 Are People Naturally Good at Detecting Lies?

In order to test whether training can improve our ability to detect lies, first we must know how good we naturally are at catching liars. If we wanted to conduct an experiment, the independent variable would be the presence of training—no training versus training. The dependent variable is what we measure. In this case, it would be the accuracy rate. Let’s look at your accuracy rate without training.

Question 1.

Ss92XgF7AgMvTSb93l8DOzoKx9yofVbryLU1rPsUUS9wY8ymWIzLJ3PRsUW+7Zv8IZOVr5oq7JV+KAA+hRGROZw8FKXvmfEg4N9Px8/d9GLP8OwDfyH7txgx3oVCi0BKxhzDPNJxwadM1tFcTTnw+DKUuNZniWwWLdHhIwfFITd95SDyAdQxE5FVOe/4fsKC8.4.2 Are You Naturally Good at Detecting Lies?

You guessed that most people have an accuracy rate of No response entered. % in detecting liars. Let’s see how accurately you guess which of these people are lying or telling the truth in the following eight videos. (You can click to make the videos full screen. And don’t be afraid to guess! Only responses to questions in the assessment section of Think Like a Scientist activities may be shared with your instructor. Your responses here are just for you.)

Question

+BSsZZMvajO5OluhWspwwZokYVnicPx4VNHhaQ==Question

nVRvXMtvXq9TqY7cs1//zVe/FBxLaDqAwhZpaw==Question

+BSsZZMvajO5OluhWspwwZokYVnicPx4VNHhaQ==Question

+BSsZZMvajO5OluhWspwwZokYVnicPx4VNHhaQ==Question

nVRvXMtvXq9TqY7cs1//zVe/FBxLaDqAwhZpaw==Question

+BSsZZMvajO5OluhWspwwZokYVnicPx4VNHhaQ==Question

+BSsZZMvajO5OluhWspwwZokYVnicPx4VNHhaQ==Question

nVRvXMtvXq9TqY7cs1//zVe/FBxLaDqAwhZpaw==8.4.3 Lie Detection Research

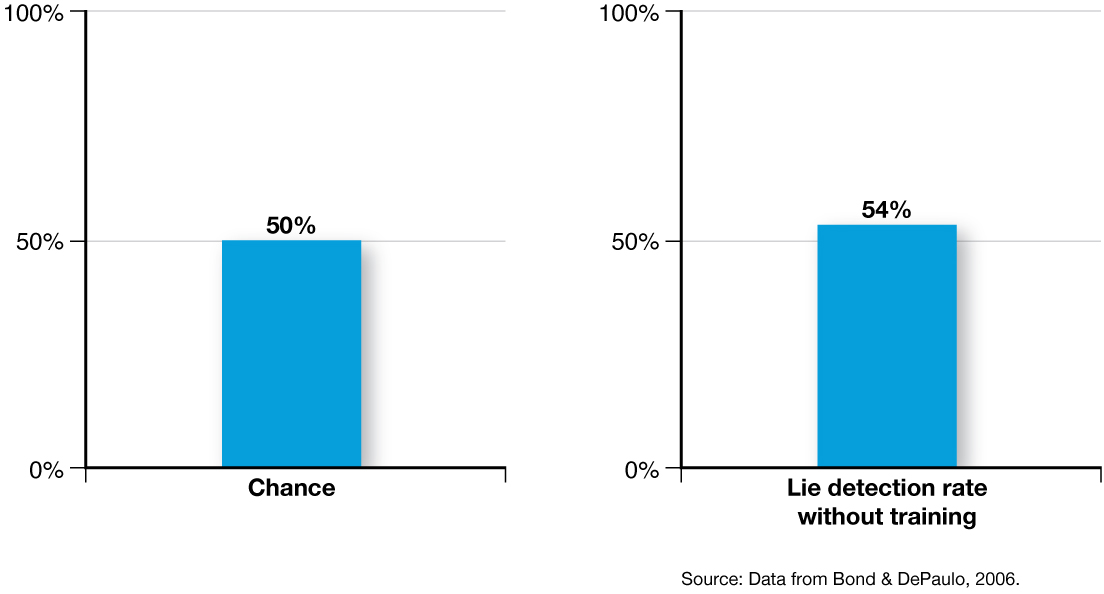

You correctly identified who was lying and who was telling the truth {model.percentCorrect}% of the time. Is that typical? Let’s look at the research on how people actually do. Psychologists Charles Bond and Bella DePaulo (2006) examined research from more than 200 separate studies that looked at the judgments of more than 240,000 people.

In many of these studies, researchers asked participants to guess whether people in videos were telling the truth or lying, much like you just did. A rate of 50% would be just at the level of chance—that is, even if you closed your eyes, blocked your ears, and just guessed, you’d be accurate 50% of the time. Across all of these studies, people were accurate 54% of the time. As you can see in the accompanying graph, 54% is barely better than chance. We’re just not very good at catching liars.

8.4.4 Test the Claim: Does Training Improve Accuracy?

Many sources, like the Web site shown at the beginning of this activity, promise to make you a better lie detector. That ad claimed it could increase your accuracy rate from 54%, which we now know is the natural rate, to a nearly perfect 90%! Let’s learn one of the strategies promoted by lie detection training programs and then test it out to see how well it works. Training programs commonly claim that you can improve accuracy by paying attention to the following signals. Please read them carefully because you will have a chance to try them out on the next screen.

- Signs of “mental effort,” such as a lower than normal level of eye contact

- Nervous movements, such as picking at fingernails or clothing

- Increased blink rate

- Increased use of filler phrases, such as “you know” or “and so on,” which give the speaker time to think

- Signs of tension or anxiety, such as perspiration or rapid breathing

Now let’s test the claim.

8.4.5 Did Training Help?

Try again with eight more videos. (Click to make the videos full screen.) Which people are telling the truth, and which are lying? This time watch for the signals that the training programs claim are indications of deception, such as how much the people in the videos look at the camera—that is, make eye contact with the interviewer. In the next screen we will examine evidence that tests this claim.

Question

nVRvXMtvXq9TqY7cs1//zVe/FBxLaDqAwhZpaw==Question

nVRvXMtvXq9TqY7cs1//zVe/FBxLaDqAwhZpaw==Question

nVRvXMtvXq9TqY7cs1//zVe/FBxLaDqAwhZpaw==Question

+BSsZZMvajO5OluhWspwwZokYVnicPx4VNHhaQ==Question

+BSsZZMvajO5OluhWspwwZokYVnicPx4VNHhaQ==Question

+BSsZZMvajO5OluhWspwwZokYVnicPx4VNHhaQ==Question

+BSsZZMvajO5OluhWspwwZokYVnicPx4VNHhaQ==Question

nVRvXMtvXq9TqY7cs1//zVe/FBxLaDqAwhZpaw==8.4.6 Lie Detection Training: The Research

Do people get better at lie detection after training? Even with training, the average accuracy rate is still only about 54%—in other words, no better than the accuracy rate without training.

Why doesn’t training improve people’s abilities to detect lies? First, research shows that no single behavior consistently and reliably indicates that a person is lying—or telling the truth (Porter & ten Brinke, 2010). Second, the kind of training required to provide even small to moderate improvement is very sophisticated and requires longer, repeated sessions that cover a wide range of complex behaviors (Frank & Feeley, 2003; Hauch & others, 2016). And even then, the effect is highly variable—nothing like the enormous effect that the ads claim will result from their training.

So how did you do? You got {model.correct2} correct, giving you an accuracy rate of {model.percentCorrect2}%.

{model.feedbackText}

8.5 Consider Alternative Explanations

3.

Consider Alternative Explanations

8.5.1 Confirmation Bias

Research shows that there are no consistently reliable markers of lying. So, why would we believe a claim that we can learn to detect lies? Despite the fact that we are not that good at detecting liars, many of us think we are. We even incorrectly think we know the “tells” that indicate when someone is lying (Bogaard & others, 2016). This is part of what makes us hopeful that we can become even better through training—and what may make us believe we are improving even when we are not.

Why do we overestimate our ability to detect liars? This is a good example of confirmation bias (Nickerson, 1998; J.C. Smith, 2010). We tend to notice and remember situations that confirm our belief that we are good lie detectors—and ignore or forget situations that don’t. So, we remember the time we caught a friend lying; it’s memorable that we bumped into her out with other friends when she said she was studying! But we don’t remember the times when we didn’t catch someone, or verified a friend was actually telling the truth.

8.6 Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4.

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

8.6.1 Advertiser Versus Academic

Think about which source of information about lie detection is likely to be more reliable—an ad or an academic journal article. In the next screen, we’ll talk about some of the differences. But first, compare the ad for lie detection training and a journal article addressing that topic.

Earlier, we noted that lie detection ads claim that training is enormously successful at improving lie detecting accuracy. Recall that our mock ad referred to “studies” and claimed that “Even beginners will improve their lie detecting accuracy rate from 54% to 90%.”

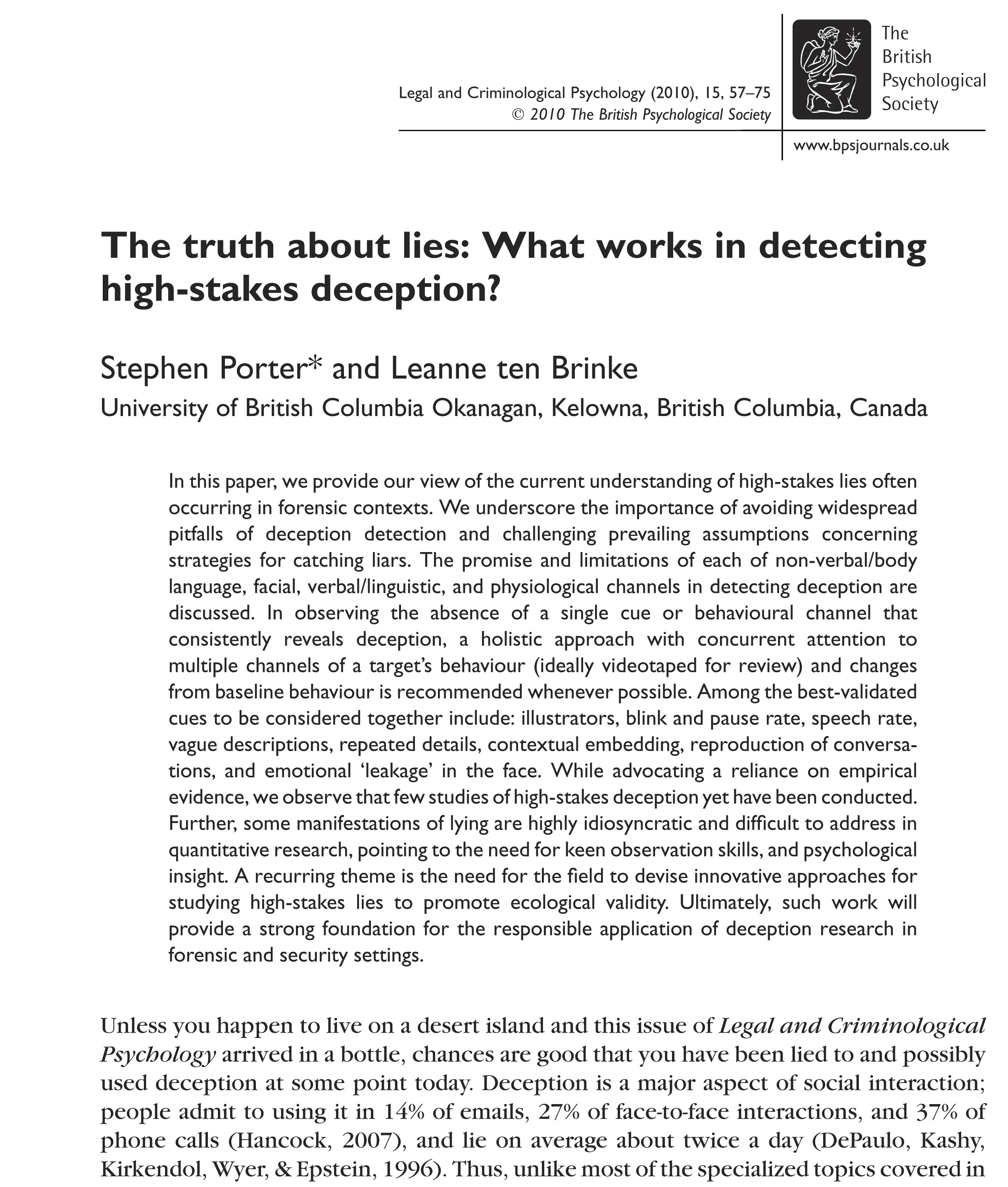

Research articles also refer to other studies supporting their claims, and include data to demonstrate their results. According to the abstract, or brief summary, this journal article gives an overview of lie detection research. For example, it includes information about how well various nonverbal cues indicate when someone is lying.

Question

mLhSSgNwJ2K93IwqDMdvw8NfSWBSV1XwzB5/m/kpImBtljh32/2UKG5fV612zzoSR5N8MYSO1PwDvEStoPq924BtyYLGM2JCaAvBeqG1O5qhawtUjPJtaVtCsvXlorVv3bVnRtjE7g2KuuFzMmh5gFqYKrXZnR75JDZ+ng==8.6.2 Source: Online Ad

Well-designed Web sites that include impressive-sounding statistics, testimonials, and eye-catching designs are developed to catch our attention. But that doesn’t mean they are our best source for accurate information. The Web site doesn’t list any scientific sources for its assertions; it refers to “studies” but doesn’t give any detail. In addition, the course developer is described as a “behavioral investigator” with no information about his educational or scientific background. Most importantly, we know that the purpose of this online course is to make money, which means that there is likely a powerful bias fueling the message that training is enormously effective. This message is likely an exaggeration.

8.6.3 Source: Academic Journal Article

The journal article doesn’t seem to suffer from these biases. Good researchers list their academic institutions along with any funding sources or conflicts of interest. This article was written by Stephen Porter and Leanne ten Brinke, both professors at the University of British Columbia Okanagan. Good research is also published in peer-reviewed journals. That means other scientists have examined the research and found it to be well done. This article appeared in the journal Legal and Criminal Psychology which is published by the British Psychological Society. Although certainly every one of us has biases that can affect our thoughts and behaviors, there is no indication that any particular incentives would influence Porter and ten Brinke’s conclusions.

So, next time you see an online ad for lie detection, ask the right questions, examine the sources, and think like a scientist!

8.7 Assessment

5.

Assessment

8.7.1 Assessment

Question

DthcnU1lEna/u7vKnXwejHCBBiNn9o9BbUQgUSZ7Ngn88Jtjo0aSfL+EEIBM4CgXHTal2GR3AjTb/Dt7YNv8gAk3v9jVQen0H2E0RQZVCmDBib3c4OBXb9HmPidYPa4qEGf+mi9SxMTw79Ujgal6yhMdkxG3ruiAaPJU6sM5CbpVvOITiS/rVz7eAN3lHSWkBZ14anhU79SlNlYK7qXf7/Dd3S7BSfChtw/DthNP5XOj/J8LBcihG55IF9JK79wQbYERal1aueXj12rpFLmU8Vy1dabP8/16ASHZmnsA+HsTw9AsZJStWUFfjEekjEdoUr6ktzx65daeNQ+6vbROCvH/emJ8bBGxneLqf4PIvTAMo4vdAx0/+3tW1Or1+SJiUobEWgjHOwRhedI9w+8TnJBNF2a3b9UkUC6NPcSAJXsLe062OGDsbwEEXDEbl/zu265DhcittZvfa1T+t5dY0aLeIaHvN0NzZ2RqW23UVmj1Ne0KoqU4wcwkNjJHlWOaqYyARxfJL3Ypq7s+z7q9+KlITbh80UBhVBhP5tRgv40CvUUlw/Gqg9UBAhZEru6WH01OUO/I15zf8GthH7hkkAEiquCkfNSALoQHgww4+Fo63CN8+NzaXYX8ZpVuUaTuE300IdUZYSZLA7VS3rVBM6s3VCDUs7+AV9OPDFpWhEiH1IpYpxB0c653GDE814a1wxZWeTCqZfbC4Dsu0vAkKxGnyp8/Miu22VFava/51Yjp3hf0Lv3Jmf1UZMrYNnKfO/x0p3q4NRIctzvGvrfLlzZsR+oGG53dq6D/bOCKwERw0EmRfc3njcLat/aIbZHUDO3ItZQLnb42QSDw8X3KmSL/4KIVVecE5X1Bbk5M0VqyrW2SjdVZRzuPZn3mrjnbsUC5IeLceSPvsAw+bjRhZ4cnMuqctkYki2hBKhpmYEDmo75QlaUp2bx+SCFbm5t40JTQIcKO5dTVaCMePejix1kzdRs6gJPmE1VWcuXzWtWytmXsYVVxfAF8B4XXexUwsllECSR3Z7JTae51pXjVnFZBOozI5todzSgWkMa8776sS3XPzoqA5TblMPts/qK8Ag7JhacI04HTXkPjezvW1ojkmcg38DR+S1V7KSUUbCLlT8Pf5T749/tsw6TnbMr1vX7rK5v9hhr5DX0C7nGgdmEfw0jfiPteZGfzbP69/UXeCUKgHFp3AH8k7Cy9+O1dQuestion

3L3WuaxOypv0XxLwl/EVZoyUfLY2pHhY8LdOZviNPkRwd4JpE7VSt4p2GDsF6NbRT/lfMJCDA+pxn+D6qITFw2uRv/BIFoRQ+cYVaAl+1jxCSY+AjaOzlUEced8G3CQklHfnJv23nh5N3d8mvtZ39vG7GA9aAMrLSNb2HEA33FenrY57Lo+QPJ4CaULG+jXjegeT/ntABgpA9kOAMwByRaSPi1M8cOZTetS26sgiDnL6feMP+UM+w9JG1WGIFGx63DbDsCdK1mFZK02an7InOUfAjYtVVmQAdMFRd6PGQd4wtVqnV32AV4Fs7ccUHNsBCpEB5JTMEUiuFdcSC+OiVyiBZ3bclDIhV0dTeW2rEQgs1nJhWApkG9ltp1nujNVgYtQ/B9t6WcUL2kEooEuBTItLfnWzYbaNunP0zXtB8XaAXAHpLkYu6AQvVOaBGxxGrwRBWrZTxqTFy7jEwqkUKrV5fwD60xqtfDgTEPVfoHGKBV/SEcvAf9sDNX5JQeUwZkScNO/nusWniWnW8M72bjH2Pch02MlMghy5WO9XLwLbRAFZCyNeLCmFWoKrUCTMyKBfo8qYNZhtT3gK6LDFtw==Question

9apf1dPLBmT+4b6fjS5CLoCdMmQyltoXq4HBdxiyPhNR5/lqzTAImgcCj8nB/5+JmDNSzPKaOrmyBVZHEyRYSISd8BUkSgg2CzkMxB5PhJL+4Kl8up04XQti3C9cG2laUMrZDYafg2iy41quXiEu7fe3bpZn3gyMABgkZTK3X+UV4o6CkissT2+eP0JylIhLWkgUtpEmTmsfgnKOz2OC6XpAaknELDebp890qxHCDOmPTgAzQ2tly7zuNH4/b/xkoXPMPQZ9AbKPMwuFDe7tsgURTKBPU2Wthc3Cfu5p2vicFIzEtptrppDyM/0VenBUr58kZfEV8LKXZAz3WFuFhhAjN41V2zxJo5IJp8kvDiaggeHVjwY2zo19e2dABQVMFCfpjOPZNxU5uz9LBfqfkf6qFrWHAQ2JcXmhTFLhh7GHwDfKH/TA74kzzAuIoel7hEDyiJHoBK5SZ38l56QMef2DKj9BGLMLpfK1udFmtbPiDz7labINqYBbRHxE//8yrWIVxspXedjdaDYwxDkpmICRNz79YJIfBRS5oTByZvd50DcwDUlCF8Aq/Y/L2CIkpPoIURiWyN+FPNURGaDhlBda5Jdm3dKBHHrVjvHPqKv5Co+vVYEH9QeZkAW6/E603GovHsqCsK3o6qTVF6V+Xw9FCHFntMRqecwrYXsD8f4Hps2RlOFHLfq/NS06Om21bzLtPfzhnfMWvKvxHwj8HKFM2x0ZW1kNVstJ369eMfUsn8UkQ8FBDnZ8QnvhA0bmMj/jVYbAZOYgwL7ti6X/suH+zgGwsrPfL1L2Ul6Jbx1Q3DeY05AITe4pd19ifj5D6PzG+LBd6YWLdyGgSsBhOPP5CHcvCnUVVa8wbfmTaUzjT6j/TrQBWIsIVOdn6vK/Vz0cN9EhJnmUr8toYybhmJOTXX4wD3gqk9vlWgy9jwLo581yJ3KM7nUssssEp6Whzblj6gee0ttURko5GswPX/1smWULazwoNKRlcRynrX783VlUomUwCxdh5xEY7PrF9xLaEWhmaUYZKlbYVDskcWsPRJYZpAZQeVUuBZzeIyaIAZHUoCXMFk3xmv7My1FbD7oh2VXbwGUk8tBBJk5fGBz+AAHrwT0EIOclhH0oT6SKnpTc5ELX4pPTToDrQz28dlyHbw+nQyN7dGCzT1sL1FahANngrtGj7v15pIIKixzCjcYZNoIMFLR8u7PS6UW/r4PDjIj28DN5qyb7tVleOGJqC/VkkYVMMdYdKAQGxKmtNgqEr7gu7RG4B/FbPeqXQoZrmA==Question