Chapter 11. Employment-Related Personality Tests

11.1 Welcome

Think Like a Scientist

Employment-Related Personality Tests

By:

Susan A. Nolan, Seton Hall University

Sandra E. Hockenbury

REFERENCES

CareerBuilder. (2012). Thirty-seven percent of companies use social networks to research potential job candidates, according to new CareerBuilder survey. Retrieved from http://www.careerbuilder.com/share/aboutus/pressreleasesdetail.aspx?id=pr691&sd=4%2F18%2F2012&ed=4%2F18%2F2099

Employment Personality Tests. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.criteriacorp.com/solution/personality.php

[Home page]. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.calipercorp.com

King, Joe. (2012). Facebook beats personality tests for predicting job success, NIU management professor finds. NIU Today. Retrieved from http://www.niutoday.info/2012/02/20/facebook-beats-personality-tests-for-predicting-job-success-niu-management-professor-finds/

Kluemper, Donald H.; Rosen, Peter A.; & Mossholder, Kevin W. (2012). Social networking websites, personality ratings, and the organizational context: More than meets the eye? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42, 1143–1172.

Morgeson, Frederick P.; Campion, Michael A.; Dipboye, Robert L.; Hollenbeck, John R.; Murphy, Kevin; & Schmitt, Neal. (2007). Reconsidering the use of personality tests in personnel selection contexts. Personnel Psychology, 60, 683–729.

Society for Human Resource Management (2011). Personality Tests for the Hiring and Promotion of Employees SHRM Poll. Retrieved from http://www.shrm.org/research/surveyfindings/articles/pages/shrmpollpersonalitytestsforthehiringandpromotionofemployees.aspx

FAQ

What is

Think Like a Scientist?

Think Like a Scientist is a digital activity designed to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. Each activity places you in a different, real-world scenario, asking you to think critically about a specific claim.

Can instructors track your progress in

Think Like a Scientist?

Scores from the five-question assessments at the end of each activity can be reported to your instructor. To ensure your privacy while participating in non-assessment features, which can include pseudoscientific quizzes or games, no other student response is saved or reported.

How is

Think Like a Scientist

aligned with the

APA Guidelines 2.0?

The American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major” provides a set of learning goals for students.

Think Like a Scientist addresses several of these goals, although it is specifically designed to develop skills from APA Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking.

“Employment-Related Personality Tests” covers many outcomes, including:

- Demonstrate psychology information literacy: Read and summarize general ideas and conclusions from psychological sources accurately [understand how literature reviews are helpful]

- Use scientific reasoning to interpret psychological phenomena: Describe common fallacies in thinking that impair accurate conclusions and predictions [identify role of confirmation bias when evidence is disregarded]

11.2 Introduction

This activity invites you to test the claim that personality tests can predict how well people will perform in a particular job. First, you will think about personality tests you have taken—or if you haven’t taken one, you can try one. You will then examine evidence about whether tests like these are useful predictors of job performance, and you will compare this against employers’ use of a different source for hiring-related personality information—social media. You’ll evaluate an alternative explanation for situations in which personality tests are less accurate in predicting job success. Finally, you’ll consider whether companies that sell hiring-related personality tests are good sources for information about the effectiveness of the tests they sell.

11.3 Identify the Claim

1

Identify the Claim

11.3.1 Can a Personality Test Predict Job Performance?

When applying for a job, have you ever been asked to take a personality test? Approximately one in five U.S. companies reports using personality tests to aid in hiring decisions (Society for Human Resource Management, 2011). Given their widespread use, it makes sense to ask whether pre-employment personality tests work well as a hiring tool. Are they effective predictors of job success?

11.3.2 What Is a Pre-Employment Personality Test?

Because you may be asked to take a pre-employment personality test one day, it’s important to understand what these tests are and how they work. You learned about empirically supported tests in the section “Self-Report Inventories” in your textbook. Self-report inventories, also called objective personality tests, help to differentiate among people based on specific personality characteristics, such as how outgoing or conscientious people are. Your answers are compared to standardized norms that are based on the answers of a large group of people. A typical test might ask people to rate themselves on various dimensions of behavior or psychological functioning—for example, “I feel comfortable around people” and “I start conversations.”

Have you ever taken a test like this? If you haven’t, try one or both of the personality tests linked here:

bcs.worthpublishers.com/webpub/psychology/hockenbury7e/redirects/personality_test_big5.html

11.3.3 Variation in Tests

Not all personality tests are based on research on personality, however. Some companies develop tests on their own. Others unwittingly use non-valid tests. You’ve probably taken a test like this before, perhaps in a magazine or online. If you haven’t, Google one and try it. There are some really goofy ones out there if you search for “personality test” and “what kind of ______________ am I?” Fill in that blank with “cartoon character,” “dog,” “car,” or even “fruit”! Just about anything you can think of will work. These tests are fun, but unlike empirically supported tests, they have not been shown to provide accurate information about personality.

How will you know if the personality test an employer gives you is a good one? You might not know. Companies rarely share such information with applicants. Bottom line: Always be yourself and take the test seriously. Personality tests often have built-in checks—questions that verify you’re answering consistently and honestly.

11.3.4 Claims about Personality Tests and Hiring

What’s the point of a pre-employment personality test? There’s no good reason for using a non-valid test, like one that tells you what kind of fruit you are. But what about an empirically supported test like the California Psychological Inventory that you learned about in the chapter on personality?

Many companies advertise the use of evidence-based personality tests to hiring companies. Let’s identify their claims. For example, Caliper, with 28,000 client organizations worldwide, claims to use data measuring personality and other characteristics to help employers figure out “which candidates have the greatest potential to succeed” (https://www.calipercorp.com).

Similarly, Criteria, whose clients include Allstate Insurance, Domino’s Pizza, and Harley-Davidson, states:

Personality tests are intended to describe aspects of an individual's character that are relevant to their job performance…. Does a candidate have behavioral traits that are statistically linked to success in this job? (http://www.criteriacorp.com/solution/personality.php)

Question

WhnAab/X6UMKaLzCgScMBQHGH8eTK55viC+NHOO6rIBku6yp137pmcngLATiXONb/Tw31j9AqDqF/G8PVH92QG7N2H2Hy9Nyg3El2btzuJRFzryieR8qtyWQ3tMTWLUOUJWC+TNnVMXYz+HvVfY1ntwqSMDShJBbtr+51ouWAPjuF3ngx+mVfmhdTDuoUsvUQoxoxGlbWvdFoy8x+b9KX8INMGJXsBGojIZZ7jzLuk+hjvCYR0w1wyuKYAoRh1ve4zfIeE6UqZgthkCj/S19mO7nk8csVqAOL/aPtuaYja9phy1q4rQQ35Tp3Xo7wmmBJ0Ij3x4NjCwZOfrNSJ5ZwoViEoDcaEPqf9Tn6w9nT23GrDdna5GIZmwC+X0usKl2el8d2yTMGwH+qcfj5rzrhLN/sVV/REflwy5SVqh+ho+XSjZG8ZjsSzhfBX5xbimdAf8yNh8om8IuEXCZ9s6mic5nfXtFyJ+KCApVn89qOLwdM5rNzQe6hWvgQaobNxa5SnPUZL2BxD6lgrVe1tmop457mVAToO7RzXrB5srQyTm6G83RoInw+wcdhSOdf+vPTJvGFVH+SAxBtESqH88IjaUVrkgC7ihbG7bAc6/3XQaGunz1sUbeRw/OkhS26r+WLobCU2HNf2tx/rapGzvv92G81GPmW+zzUjSo3peD3iFe3r2adJFGlq8ptwvy4van3DImxyMP1aTUcclkBDncECTs1Gl55GSZiUI97o9U97dTVK/BgyXSL+vVYYzpuw4ikDQCqGDpvqQ=11.4 Evaluate the Evidence

2

Evaluate the Evidence

11.4.1 The Research on Pre-Employment Personality Tests

So, is the claim true? Can the outcome of a personality test really predict job success? Thinking like a scientist involves considering all of the available evidence. There has been a lot of research on this topic, but it’s often quite contradictory (Morgeson & others, 2007). Reviews, which are journal articles that describe a number of studies on a given topic, can help us to come up with an overall conclusion about a body of research. So, let’s look at a review on personality tests and hiring.

One team of researchers reviewed more than 7,000 articles on personality testing (Morgeson & others, 2007). None of the researchers has a stake in the companies that sell personality tests. So, they are objective in their review of the data.

11.4.2 The Results of a Research Review: Faked Responses

The team drew two main conclusions in their review. First, it is impossible to prevent people from faking their responses on personality tests. If you went online to take one earlier in this activity, did you find yourself tempted to respond in a way that would help get you hired—even if you had to fake it?

Below are questions that might show up on a pre-employment personality test. If this were part of a real test, you would indicate how strongly you agreed or disagreed with each statement. For this activity, however, indicate for each item whether you would definitely tell the truth or would be tempted to stretch the truth.

Question 11.1

Z2FHwpKENfH1/A2zhGiORWKYb7Qvy71bKC7xYY6pakN4hg45OSmQP6m+/c3GsSOjoY43c6THAPLWHXrfKNFhhTLMhto8XdS8h25V76X4YWG4cTu5ABhlX5CtyldP2tWmOlux+Z1bwSLhO80TtF2BsM5oZj6KrsHnpundoyHuYe43rNY9e4WTnRUJtM1J5VnMyVkzfo6LacMhMd/rqLwNgeffYdHWc87XoU6SFfO+uZwObzn//n4rcpx7A04MDZ6/rg/o+2rtbXLbJNrBg84HjxYDICw= zlT6c7clMK4QwnaQZxEZ8vB/yxrPZ+1/FZuhFucSB/npX+m8Up6u7LaYz7r+1Dc3hpLBTQBqdG6CSMhL928WJLF/tmK/Gw+Ds6/Fm6j9Rb2HFbAfUx8913vqTZDKNFje3wDqMoAgrEWgATftS6vCpVraoHsEoNuLTIlv+SfmR2C6uJ1c4+7L2ky8EkD7gL9V7GUtbKVj+dycRxqj7YR6d35qIM67ClTv5Ypio5rwjK0PR05z/E7AMvmG0j/osb6SpxEzQb22DEwG7ta+ryZWrJmpmnGjDCqfS5yFlUx0rnNtPrig0KJCa2BasSA= uys7iLJVpK6Qhmrls4cuP8XNtJBcGV5Hn4m5m0odBVUyqD1PIh26DaDj+SHgz6CZe7LxvWdAnnic613QHWdB33pAUtRxAdDxKDI1cX2gM2yl7f4CQJ0OWacdtTGJCrV2hMY0cEA17Ha2eOSXvO0P6/wTC5nE9LqCUEUvpro8XU+I0sL0rQTlFqB80CfE7Lcmdsogxu3lfw/teFvQ/rWhfBkPKFmZP0XktpEgdzpw3nNcM3dD/0IXduOzQKrZpIKxWEjyAQ6PxVBs5FZd o0ix4enYZ3Me6C0CxeSsU7b4yW4RMViUXP9tZQK6uNFYibiBqMPkM9+9A/Xa+oy1lEaO/oIfEKWPnc8Yt/EsEo6nnM5N8Ga5Qa68lNoVywpXMaT7Z6Z/bd8F9iGmf5DiJKr1VtncpcYWxadtnbV9r8qTWoXz6ZaUHgXLiywzyBhJ+z151gB3wjXXPtbI4PHYS2NFTzbX5S2OJYA9NyXurKbmQ2HH2G1Ir4nmiY6z31FLe689QmpnvLU5LKNx+A5PtBU+TDOmUVx9H5EPaF0VQ4ZPzE4Vy1Y4 GwWSS1DNjMY3hfoqvifQVRqzRbYQfgyYFg08bgtsiOEeq8Ki6ON4kUo25CsLVKRowpDOgmFVG1WE7rVKONNkhKJatn4qJODyPznP2b4XY7oSOYLElxnnKskp2J5Ug9Pf8rlyTnlMYBkNSAOWR91WvW/UWX4Sg1ey4bOp4qMa1VdnJ58bloD1x1RaPrsyFevYK5CUiLTaADIj3X/362mgkt1osD4819e9nYUBAbghFkXhFpAu3RNU8NL1PkL76TUVgP8olsivyhnmmxxWQ3S3zpjNZUlQEXWSPnwHynxykHWqoL7Ml94bD1vYXzsFhgx8 yTsHFQ64f/S44VHSmIDZ2v4zp09fiHKizcCh/P6ULHbw7BFz+LIPnK1R5QRaN/+DmAUo0Gx6LndtSUnhy53pkeRWkFfdF8iPp8OE51QQBusX7pHwnyiA9QxLqonqEa1EGiKWPsYWH9oeGDUeCX8lb26nPdePgX49ZnNqANGnBiKQ8il+wiJMmsFQadb832Eks7X57qhbQka+GqaMRd/FdGcTW7zibJsGWUQRjO7UwPpTrAxFM+PJuxL0I6CGhhU6iTXQYrtHgCKxbi/8CTw3HrZNrSPWb2wEXuVElP5bczmLPPgfk6G7qA== KG+ZdsLn7eaNSViBFJKtNoxKjPzOQrAeReI3OB8F33fFKGQT+200Xy/0KyhxO/tYrfmL4bwQZe6aYGgBxYlIsBNcky/FwgPJj6wUY3kSO1LLlQgj2Xdzo2Ff6yztiQQx+w4LTWoBq/PLNZN3CiXxGf68G4cuiPP4h4f7Qk/d0CTFBrqnR68Ap5Nk5hgen+r5/KkTdtuQ6sUi98acFvPJvc+C1tRzbP5TTF1RxbJijgw7LzyRNLmjYKe5vgPd37iD/c9+1T4qAY2En4LXSuINJviSnIbB2s2YMAI8CSjkZWI=11.4.3 The Results of a Research Review: Poor Predictors of Performance

The team of researchers also concluded that personality tests are just not very good predictors of job performance. This was demonstrated, for example, when tests identified people as “good fits” for a job, but these people did not later receive positive supervisor ratings.

If you went online earlier to take a personality test, did you feel that your results would be useful to an employer? Despite claims to the contrary, research does not support the usefulness of personality tests for hiring—even when they are “good” tests based on the research on personality. As much as we’d like them to be, personality tests are not some kind of crystal ball that lets us see secret check marks or x-marks over the head of each candidate.

11.4.4 Facebook as a Hiring Tool?

In fact, personality tests are so poor at predicting job success that social media might be a better option. According to one survey, almost two-fifths of companies use social media when making hiring decisions, about double the number of companies that use personality tests (CareerBuilder, 2012). So, how useful is this tool to companies?

In one study, students completed personality tests and allowed their Facebook profiles to be quickly evaluated by trained raters (Kluemper & others, 2012). The students and raters tended to agree about the students’ personalities. Six months later, researchers received performance evaluations from students’ bosses.

Question 11.2

HpM6WVerb6wNY40euViSYnD6RXlhCOKhFLhldMCnXvUE4w715WTuddzw5wk9Tcf4OapW42kRaKrRPwb94RunN7mzCR8jbLfRpMTCfccajjDGbkiOplZmfRLrgGKPtwgFdm3sKaC/u0tiURaZwo/K4+BTOojaCHeWRJ2cLFVk+tGyVLLZJJIbgeCTver2EX+maDDdIkNvhRfKvfpu84sGMHS+A/2f6QQ5PhfVJpmW7UEIM/3oPwKQBpmJMMtGCqfDE5Mo8kAiFkn815ATA+GeE6hPv35usAg2iYliJ9vscxm6arMznXaAv977HYoIHDaqs30R6u7PyXQmUDdEu25X+hVR5X/8uwp9Pg6Z/cMdkcdPeLONkWrjPfGiTWWLVlf4UkQ1u/DHb96MjzDmHqQHrfXlHCEh4ct49TJ5sg==

11.4.5 The Problems with Screening Job Applicants Using Facebook

Are you surprised that employers look at candidates’ Facebook and other social media when making hiring decisions? After all, an employer can run into a lot of problems with that tactic (Kluemper & others, 2012). Click each category to learn more.

Legal problems:

Social media could contain information that an employer is not legally allowed to use in hiring decisions, such as details about a candidate’s race, disability, or family status.

Reputational problems:

Companies might develop a negative reputation for using candidates’ social media as a resource for hiring. Some people find the practice intrusive. Others resent the lack of any opportunity to address concerns.

Problems with equal treatment:

Companies routinely gather the same information from all candidates—for example, résumés and recommendations. But not everyone participates in social media to an equal degree. Use—or non-use—of social media could put some candidates on unequal footing.

11.4.6 You’re the Boss

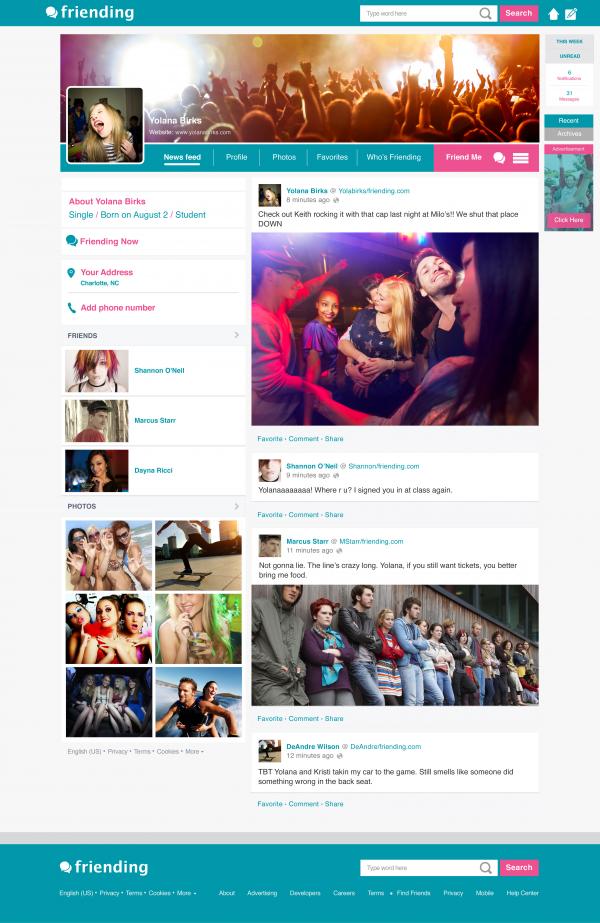

Regardless of the problems with personality tests, twice as many companies use social media as use personality tests when hiring. Let’s see how this might work. Imagine you’re an employer who wants to hire a server for your new upscale pizza restaurant. What kind of person do you want to hire?

Question 11.3

yxO5IHQYgSTfEnvGrx+M0sgGa9Xlxfb8moYlglpfoWTgiZRTA2dCl9JKZfyGMzx6AiItWnmjvgFCbpYOXWh38YRBURym8iAhZ9pmID3/XNCBE9KJf5YLZcv/VeoX6ZYpgSLacLQ/3twLARGQRS3d/AIq7Q3U74mkF1XghUrcEX+axebxnZoBU+tZuDYRV0fx11.4.7 Reviewing Social Media: Candidate #1

Now look at three fictional social media pages for your pizza server candidates. These appear below and on the following two screens. What is your gut reaction to each profile? For each person, write a sentence about her personality in the essay box below her profile. (Click to enlarge the profile image. You can click a second time to enlarge it more. You’ll then have to return to the main screen.) What was it about the page that led to your conclusion about her personality?

Licensed Material is being used for illustrative purposes only; person depicted in the licensed Material is a model.

Question 11.4

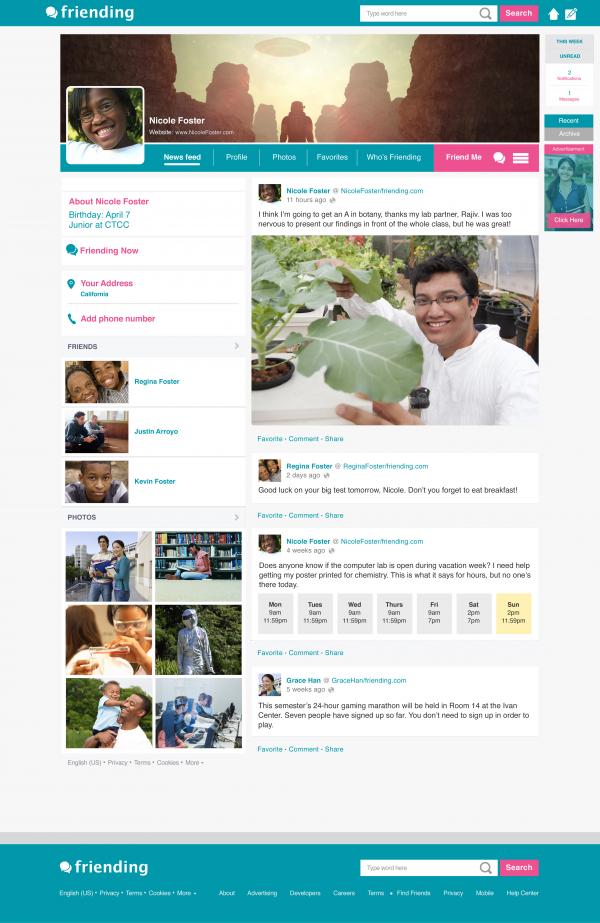

snByA+gbH414Bn9ZPCHnGz5j+bJaRyfVU0UDU1U0BNJsReHmhwRRqokvbDf6tLrxGm9FkMaPPcTU2gfIR5eBEw==11.4.8 Reviewing Social Media: Candidate #2

Licensed Material is being used for illustrative purposes only; person depicted in the licensed Material is a model.

Question 11.5

pEbsvA7lkl7dMODRX2+1smebOsFh7/RstNvJF7F4PSdyPhm2qmIzf0YXzXfjnvSBSDFl1vRxDJxEfD4Ehkf8Lx22A63hLogwHO7mSLrwqYbxGfCn+iPrMLjt7D8sihl31IfwEMEiJ/dte9CaYdhvNEgSlU7KELjBPBK10g==11.4.9 Reviewing Social Media: Candidate #3

Licensed Material is being used for illustrative purposes only; person depicted in the licensed Material is a model.

Question 11.6

8JPyu2yb+BRlFSivw7E0ZESnmwTCzghsrZjH+EpITlfAj2ev5pr8iS4VzfLGgjZ3lbaSlxTIYttuV9DHaivID7gXabzbkFv+m4q8vG4VG771XQwK9FiFGsJ2BVPY9vFroMEs1fhmSTV+onRlip9eeroGPVR8VG/xzSu1Jg==11.4.10 Whom Would You Hire?

Based only on your sense of their personality from their social media pages, which of these three job candidates would you hire? Click the box below your choice.

You wrote:

New Paragraph

Hire

You wrote:

New Paragraph

Hire

You wrote:

New Paragraph

Hire

Question 11.7

zjzIKYw8O87tVRprpqT3qB0IMKViX3tw+PurnwQqwJlD4zQz/iZxEJtCcfjjnySHNUnuc2a77a37s4CJc51W9w9kUaVRZCeCe+T99PqSCZv3jINaDiBFMDokQOgj9W8zgrOiMlBG9NeyXi8gQTy/7NmNAfQTmwmUxmDfXmtFdDHv3AOzMNGSHWj9T2NETvaBH5zJS4pG++m+TUeK2SnpGMa+eZJ3g1ovQSqdCmFqgAbJT+GXXjket+l+kyPQU2lm16zm7hW5wy9j/eMWSD1QIjS/8kqhmLFxooDBPGT6OMo3TBwxwfIO1jBnU4R1R1EQ11.5 Consider Alternative Explanations

3

Consider Alternative Explanations

11.5.1 Faked Answers

With so many problems surrounding the use of social media as a hiring tool, it was surprising even to the Facebook researchers that it outperforms personality tests (King, 2012). When research findings are surprising, a scientist will consider alternative explanations.

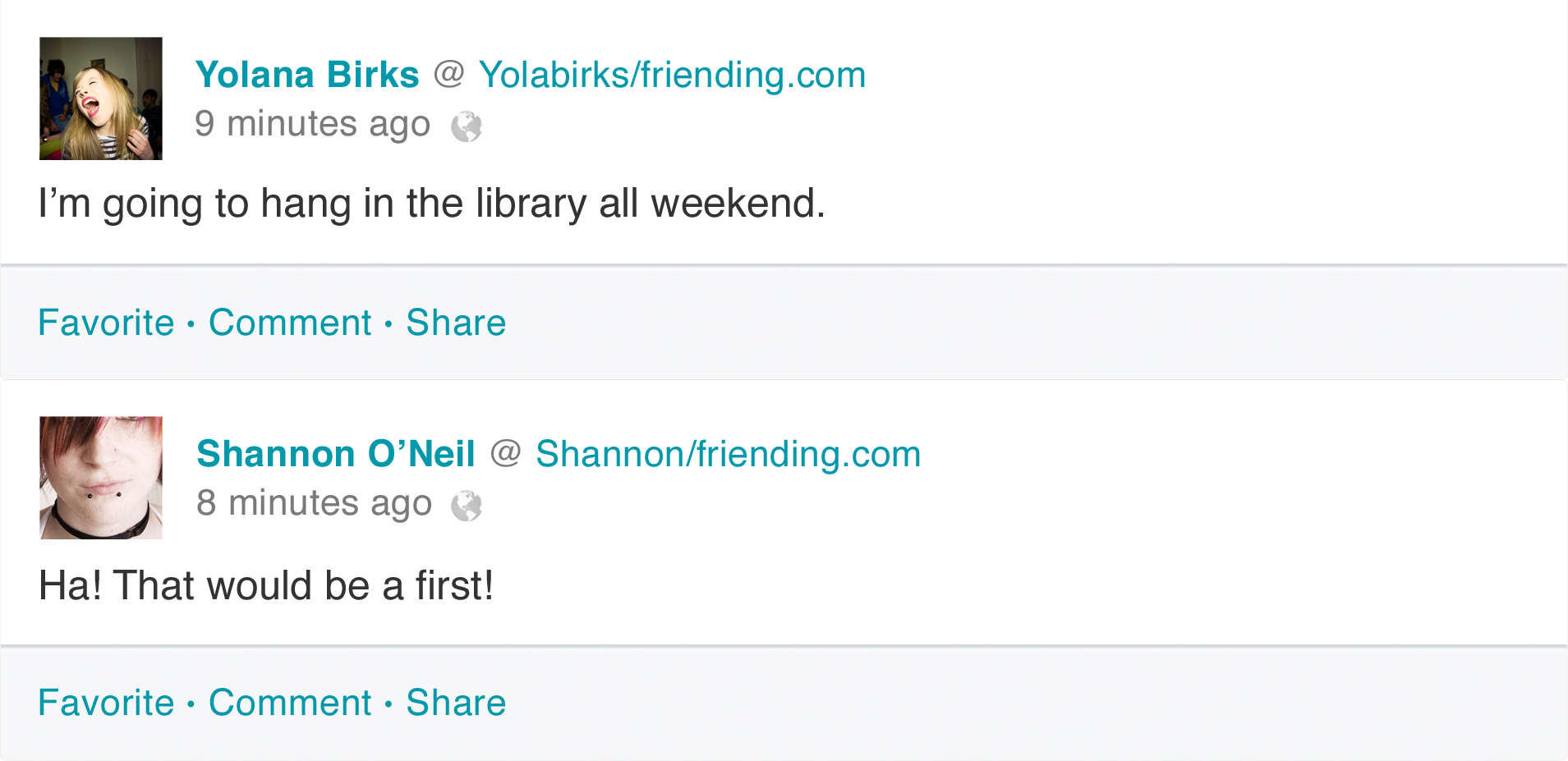

Why might personality tests not be as useful as hiring organizations think they are? One reason is that, as we noted earlier, people sometimes give false information on personality tests (Morgeson & others, 2007). As the lead researcher on the Facebook study said: “Personality profile questionnaires are subject to people providing what they think is the socially acceptable answer. It’s harder to do that on Facebook—your friends will call you out” (King, 2012).

11.5.2 Faked Answers or Something Else?

Another explanation has to do with how well personality test questions connect with the qualities that companies seek. Some questions may be flawed (Morgeson & others, 2007). For instance, one item asks respondents whether they see themselves as having “leadership qualities.” But what does that mean? Someone who is an effective leader in one context—the leader of an orchestra, for example—might not possess the qualities to lead in another occupational setting—say, as the captain of a fishing boat, or as a kindergarten teacher. If the employer and the respondent are not thinking about the same personality characteristics, the question is meaningless.

This problem prompted the review authors to caution against using personality tests at all when hiring employees, unless the questions are directly related to the job requirements (Morgeson & others, 2007).

11.6 Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

11.6.1 Pre-Employment Test Companies as a Source for Information on Effectiveness

What sources do employers turn to when considering whether to use a personality test? Often, it’s the companies that sell these tests. Both of the hiring assessment companies that we described earlier refer to research supporting their claims. Caliper’s Web site cites “prestigious publications” that have featured their work (https://www.calipercorp.com), and Criteria’s mentions their “Scientific Advisory Board, which is made up of leading psychologists and test development experts” (http://www.criteriacorp.com). But how can these companies talk about their grounding in science if personality measures haven’t been shown to be effective as hiring tools?

11.6.2 Looking at the Big Picture

Science, when taken piece by piece, is often contradictory. It is only when scientists look at the fuller picture across many studies that a consensus starts to emerge. Remember that there is a tremendous amount of research on this topic—more than 7,000 articles! If you only look at some of the research, you might get an incomplete picture.

It’s possible that people marketing pre-employment personality tests are aware of negative reports, but ignore them. Their goal is to market the test, so they focus on good news. It’s also possible that they are subject to confirmation bias; that is, they may notice the studies that match what they believe about their tests and fail to notice those that do not. The bottom line: When there’s money involved, always look at the big picture made up by many studies, not just what is highlighted by those who stand to profit. Only then can you see the broader story the science is telling.

11.7 Assessment

Assessment