Chapter 4. Multitasking

4.0.0.0.1 Welcome

Think Like a Scientist

Multitasking

By:

Susan A. Nolan, Seton Hall University

Sandra E. Hockenbury

With the assistance of Scott Cohn, Western State Colorado University

REFERENCES

Alicke, Mark D. & Govorun, Oleya. (2005). The better-than-average effect. Mark D. Alicke; David A. Dunning; & Joachim I. Krueger (Eds.). The self in social judgment. Studies in self and identity (85–106). New York: Psychology Press.

Finley, Jason R.; Benjamin, Aaron S.; & McCarley, Jason S. (2014). Metacognition of multitasking: How well do we predict the costs of divided attention? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 20, 158–165. doi:10.1037/xap0000010

Gaspar, John G.; Street, Whitney N.; Windsor, Matthew B.; Carbonari, Ronald; Kaczmarski, Henry; Kramer, Arthur F.; & Mathewson, Kyle E. (2014). Providing views of the driving scene to drivers’ conversation partners mitigates cell-phone-related distraction. Psychological Science, 25, 2136–2146.

Ophir, Eyal; Nass, Clifford; & Wagner, Anthony D. (2009). Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 106, 15583–15587.

Sanbonmatsu, David M.; Strayer, David. L.; Medeiros-Ward, Nathan; & Watson, Jason M. (2013). Who multi-tasks and why? Multi-tasking ability, perceived multi-tasking ability, impulsivity, and sensation seeking. PLOS ONE, 8, e54402. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054402

Schroeder, Paul; Meyers, Mikelyn; & Kostyniuk, Lidia. (2013, April). National survey on distracted driving attitudes and behaviors – 2012. (Report No. DOT HS 811 729). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Strayer, David L.; Watson, Jason M.; & Drews, Frank A. (2011). Cognitive distraction while multitasking in the automobile. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 54, 29–54.

Watson, Jason M., & Strayer, David L. (2010). Supertaskers: Profiles in extraordinary multitasking ability. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 17, 479–485.

FAQ

What is Think Like a Scientist?

Think Like a Scientist is a digital activity designed to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. Each activity places you in a different, real-world scenario, asking you to think critically about a specific claim.

Can instructors track your progress in Think Like a Scientist?

Scores from the five-question assessments at the end of each activity can be reported to your instructor. To ensure your privacy while participating in non-assessment features, which can include pseudoscientific quizzes or games, no other student response is saved or reported.

How is Think Like a Scientist aligned with the APA Guidelines 2.0?

The American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major” provides a set of learning goals for students. Think Like a Scientist addresses several of these goals, although it is specifically designed to develop skills from APA Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking.

“Multitasking” covers many outcomes, including:

- Use scientific reasoning to interpret psychological phenomena: Describe common fallacies in thinking that impair accurate outcomes and predictions. [consider overconfidence]

- Use scientific reasoning to interpret psychological phenomena: Use psychology concepts to explain personal experiences and recognize the potential for flaws in behavioral explanations based on simplistic, personal theories. [compare personal belief and scientific findings]

4.1 Introduction

This activity invites you to test the claim that many people are good at multitasking. First, you’ll get a chance to see how well you can multitask. You’ll then examine recent studies about whether most people are actually good at multitasking. Next, you’ll explore alternative explanations for why people believe they can multitask well. Finally, you’ll consider the source of our belief that we’re good at multitasking.

4.2 Identify the Claim

1

Identify the Claim

4.2.1 Do You Multitask?

Do you ever try to do more than one thing at the same time? Are you good at it? It’s possible you’re multitasking right now. Do you have other applications open on your computer? About 70 percent of people think they are better than the typical person at multitasking (Sanbonmatsu, 2013).

4.2.2 Multitasking While Driving

One particular type of multitasking has been in the news quite a bit lately—multitasking behind the wheel. Do you dial and drive? Or perhaps worse, text and drive? A recent National Highway Traffic Safety Administration report found that approximately half of U.S. drivers operate their vehicle while distracted (Schroeder & others, 2013). At least some of the time, drivers eat, talk on the phone, text, or read while driving. Twenty percent of people even report that they have put on makeup or shaved behind the wheel!

Most of these distracted drivers probably believe they can multitask safely, and there are no statewide bans on most of these activities, including using cell phones while driving. Yet, most states do prohibit texting while driving, and several require the use of a hands-free device for talking on a cell phone while driving. It seems plausible that people can safely use a hands-free device to talk on a cell phone while driving, but is this true? Are we good at some kinds of multitasking?

4.2.3 Identify the Claim

We’ve talked about what most of us think about multitasking generally, as well as multitasking behind the wheel. Before moving on to evaluating the evidence about multitasking, let’s identify the claim we’ve been discussing.

Question 1.

Which of the following summarizes the claim?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

4.3 Evaluate the Evidence

2

Evaluate the Evidence

4.3.1 Test Your Multitasking Skills

So let’s see how good you are at multitasking. In this activity, you will complete two tasks. The first task requires you to listen to a story and respond to the words “left” and “right” as you hear them. The second task involves exchanging text messages with another person. You’ll first attempt each task individually. Then, after you’ve tried each task, you’ll attempt both tasks at the same time. Neither task is particularly difficult, but doing both at the same time will require you to switch your attention back and forth between the two tasks.

4.3.2 Left or Right with the Wrights

In this task, listen carefully to the first half of “The Wright Family Story” while pressing the left arrow key on your keyboard (or clicking the left button on the screen) each time you hear the word “left” or the right arrow key on your keyboard (or right button on the screen) each time you hear the word “right” or “Wright.” In order for your response to be correct, you must correctly press or click either left or right within 1 second of hearing “left” or “right” or “Wright.”

4.3.3 The Texting Activity

In this next activity, you will text responses into a simulated cell phone (actually just your keyboard). Like normal texting, incoming messages will appear on the screen. Then you must respond with a text message of your own. For this activity, the response you need to type will appear in red above the text window and then you must text your response immediately. To do so, simply type the exact same message in the text box using your keyboard and then click on the word “Send.” You’ll receive one point for each message you send where all the words are spelled, capitalized, and punctuated exactly like the original message.

4.3.4 Time to Multitask

Did you find the left/right task or the texting task challenging? You probably didn’t, but now try doing them both at the same time. Remember, you can use the left and right arrow keys or the left and right buttons, whichever is easier for you.

4.3.5 How Good Were You at Multitasking?

So how did you do at multitasking? Were you surprised at your score when you did both tasks at the same time?

Question 2.

Which answer best describes how easy it was to multitask in this case?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

4.3.6 Multitasking Rates

Let’s look at some general research findings about multitasking and then explore one study of multitaskers in more detail. [] Researchers estimate that just over 97% of people perform more poorly when multitasking than when just doing one task at a time (Watson & Strayer, 2010). Researchers found that just 2.5% of us are good at multitasking. These people are called supertaskers.

4.3.7 The Equivalent to Being Legally Drunk

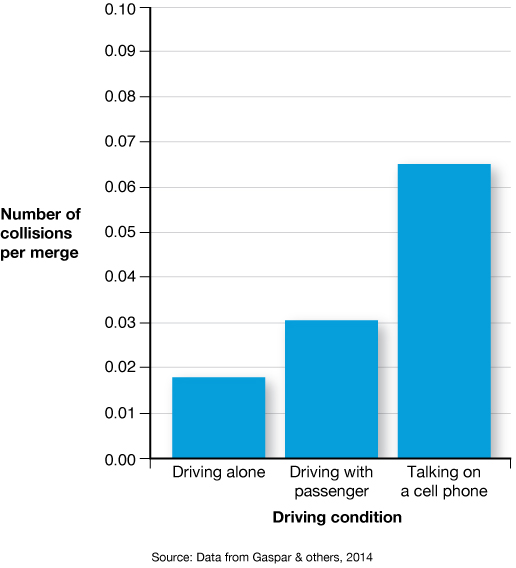

Unfortunately, many more than 2.5% of people engage in multitasking, including the dangerous behavior of multitasking while driving. And those who frequently multitask with media—texting while writing a paper, for example—are both less proficient at multitasking in general and, frighteningly for those of us on the road, more likely to multitask while driving (Sanbonmatsu & others, 2013). How dangerous is this? In one study, researchers reported that carrying on a conversation while operating a driving simulator resulted in driving impairment equivalent to being legally drunk. This was true even for participants using hands-free devices (Strayer & others, 2011). Another study of participants using a driving simulator demonstrated the dangers of talking on the phone (Gaspar & others, 2014). A conversation on a cell phone led to more accidents while merging than driving alone. It also led to more accidents than simply talking with a passenger—because a passenger can adjust his or her behavior in response to the driving conditions.

4.3.8 Studying Multitasking

What about multitasking in other situations? If you’re not risking a car crash, can multitasking be helpful? In order to explore the effects of multitasking, researchers compared people who multitask a lot with people who rarely multitask (Ophir & others, 2009). These two groups were determined by asking people about their behavior when “consuming media.” For example, do they use multiple devices at once or watch TV while looking at information online? Do you think of yourself as a light multitasker or a heavy multitasker when you consume media?

Question 3.

| A. |

| B. |

4.3.9 The Effects of Multitasking

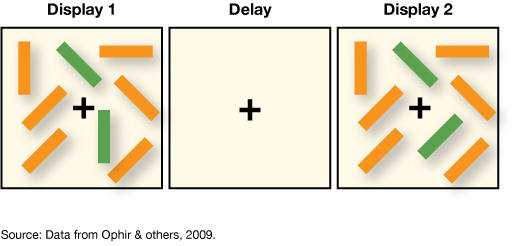

The researchers asked both the light multitaskers and the heavy multitaskers to complete several cognitive tasks, including the one shown here. Participants see one display flashed very briefly. It’s then removed for about a second before a second version of the display is shown. The task is to identify whether either of the green bars has changed its orientation, while ignoring the orange bars, which are distractions. In the figure here, for example, the green bar on the bottom shifted from vertical to diagonal. So who do you think performed better on this task, light multitaskers or heavy multitaskers?

Question 4.

| A. |

| B. |

4.3.10 Multitasking and Cognition

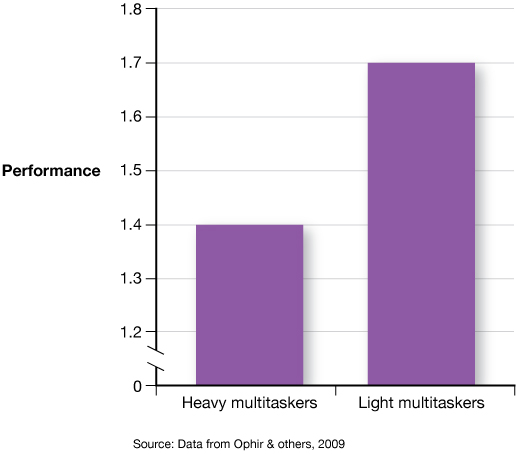

You guessed the multitaskers would perform better on this task. As you can see in this graph, on average, the light multitaskers were better at tuning out the distraction of the six orange bars than the heavy multitaskers were. The researchers believe this finding suggests that heavy multitasking makes it harder to tune out distracting information. The suggestion is that multitasking impairs at least some cognitive abilities. Other researchers have made similar findings (Sanbonmatsu & others, 2013). In fact, they concluded that people “who chronically multi-task are not those who are the most capable of multitasking effectively.”

Earlier you said that you were more of a multitasker. Does this finding affect how you think about your own habits?

4.4 Consider Alternative Explanations

3

Consider Alternative Explanations

4.4.1 Overconfidence

All the research points to the fact that most people can’t multitask effectively. Why not? Multitasking involves the division of attention—and attention is a limited resource. When you try to pay attention to more than one task at the same time, your performance on both tasks suffers (Finley & others, 2014). [] In fact, in terms of probability, there is only a 1 in 40 chance that any individual person can actually multitask effectively. So why do most people think they are good multitaskers? One reason is that people are often overconfident about many of their abilities in general (see Alicke & Govorun, 2005). And multitasking is one area in which people are overconfident (Sanbonmatsu & others, 2013). Unfortunately, this confidence is often misplaced. According to researchers, more than 70% of college students believe they are above average at multitasking. In actuality, people who multitask the most tend to be the least capable at tasks requiring multitasking (Sanbonmatsu & others, 2013). We also learned that heavy multitaskers tend to perform more poorly than light multitaskers on some cognitive tasks (Gaspar & others, 2013).

Question

In the box below, provide an example from your daily life where you attempt to multitask. Do you plan to change your multitasking behavior in light of the research on multitasking?

4.4.2 Inattentional Blindness

Here’s another explanation for why most people think they can multitask: They don’t know what they’re missing. It’s likely that this actually leads to some of our overconfidence. If we don’t notice when we miss things, we don’t realize that we’re not as good as we think we are. Maybe you walked right past your best friend because you were too busy checking out Instagram as you crossed campus. Or maybe someone talking on the phone ran through a red light right in front of you. In many cases, people don’t realize what they missed because they were too distracted. As you learned in the chapter on consciousness, this obliviousness is called inattentional blindness. This occurs when our attention is drawn to one task, and we fail to notice important events that are clearly in our field of vision.

4.5 Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4.5.1 Personal Beliefs vs. Scientific Findings

The claim is that most people are good multitaskers, at least in some contexts. However, it turns out that very few people can actually multitask well, and those who multitask often can experience negative consequences. In this case, the source of the claim is likely our personal beliefs. However, thinking like a scientist often means that we need to set aside our personal beliefs when they don’t agree with scientific findings. Ignoring the scientific research and being overconfident in our ability to multitask can put our lives at risk and impair at least some of our cognitive abilities.

4.5.2 When Nearly Everyone Believes They Are Part of the Special 2.5%

People seem to lack an understanding about how difficult it is for the human brain to switch between two different tasks. Too many people think they are part of the special 2.5% who can multitask effectively. Distracted drivers often fail to notice how dangerously they are driving as they also attend to something other than driving. As this video shows, people shouldn’t even try to text while doing something as simple as riding an escalator.

4.5.3 The Myth of Multitasking

For almost everybody, the ability to multitask is a myth. Yet, people continue to believe they can multitask effectively. Earlier, you wrote about an example of multitasking in your daily life, as well as how the research on multitasking has made you think about your current behavior. You said:

For most of us, multitasking might be wasting hours of productivity every day. The example you provided might be a good place to begin breaking the habit of trying to multitask.

4.6 Assessment

Assessment

4.6.1 Assessment

Question

Psychological research on multitasking has shown that:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |