Chapter 6. Eyewitness Testimony

6.1 Welcome

Think Like a Scientist

Eyewitness Testimony

By:

Susan A. Nolan, Seton Hall University

Sandra E. Hockenbury

REFERENCES

Frenda, Steven J.; Nichols, Rebecca M.; & Loftus, Elizabeth (2011). Current issues and advances in misinformation research. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 20-23.

Innocence Project. (n.d.). Eyewitness misidentification. Retrieved from http://www.innocenceproject.org/causes-wrongful-conviction/eyewitness-misidentification (2013)

The Justice Project. (2007). Eyewitness identification: A policy review. Retrieved from https://public.psych.iastate.edu/glwells/The_Justice%20Project_Eyewitness_Identification_%20A_Policy_Review.pdf

Loftus, Elizabeth. (2013). 25 years of eyewitness science……finally pays off. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8, 556-557.

Megreya, Ahmed M., & Burton, A. Mike (2008). Matching faces to photographs: Poor performance in eyewitness memory (without the memory). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 14, 364-372.

Watkins v. Souders, 449 U.S. 341, 352 (1982) (Brennan, J. dissenting).

Wells, Gary L., & Olson, Elizabeth A. (2001). The other-race effect in eyewitness identification: What do we do about it? Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 7, 230-246.

FAQ

What is Think Like a Scientist?

Think Like a Scientist is a digital activity designed to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. Each activity places you in a different, real-world scenario, asking you to think critically about a specific claim.

Can instructors track your progress in Think Like a Scientist?

Scores from the five-question assessments at the end of each activity can be reported to your instructor. To ensure your privacy while participating in non-assessment features, which can include pseudoscientific quizzes or games, no other student response is saved or reported.

How is Think Like a Scientist aligned with the APA Guidelines 2.0?

The American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major” provides a set of learning goals for students. Think Like a Scientist addresses several of these goals, although it is specifically designed to develop skills from APA Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking.

“Eyewitness Testimony” covers many outcomes, including:

- Interpret, design, and conduct basic psychological research: Define and explain the purpose of key research concepts that characterize psychological research [identify independent and dependent variables in a study]

- Demonstrate psychology information literacy: Describe what kinds of additional information beyond personal experience are acceptable in developing behavioral explanations [compare the legal system and psychological science as sources of information about eyewitness identification]

6.2 Introduction

This activity invites you to test the claim that eyewitness testimony is typically accurate in identifying perpetrators of crimes. First, you’ll get a chance to be the eyewitness to a crime. You will then evaluate studies that have systematically examined the accuracy of eyewitness identification and testimony. Next, you’ll consider alternative explanations for these research findings. Finally, you’ll compare the legal system and psychological science as sources for information about eyewitness identification.

6.3 Identify the Claim

1

Identify the Claim

6.3.1 Are You a Good Eyewitness?

Eyewitness testimony is widely used in criminal court cases, in large part because most cases don’t have biological evidence such as DNA (The Justice Project, 2007). And it works—that is, it helps to convict people. In the words of the now-deceased Supreme Court Justice William Brennan, “there is almost nothing more convincing [to a jury] than a live human being who takes the stand, points a finger at the defendant, and says ’That's the one!’” (Brennan, 1982). But just because eyewitness testimony is convincing, doesn’t mean it’s accurate. Thinking like a scientist involves asking good questions. So, just how accurate is eyewitness testimony? If you witnessed a crime, do you think you could describe the perpetrator, and then later identify him or her? Let’s try it. Watch the video clip here. It shows a group of 10 volunteers partway through a day of memory tests they were taking for a TV documentary.

Warning: This video stages a violent crime and contains strong language that some may find offensive.

6.3.2 Who Did It?

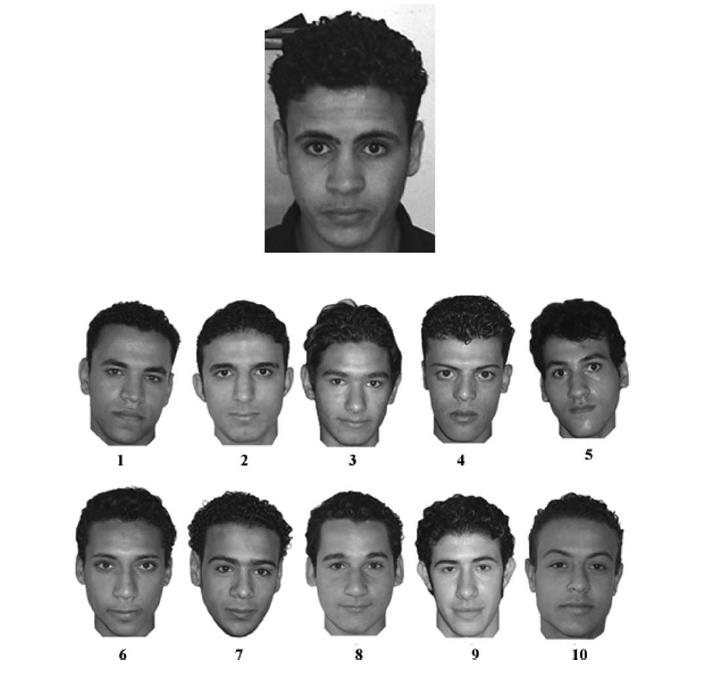

You were just an eyewitness to a crime. Can you ID the person who committed the murder? Look closely at the ten photos shown here.

Question

KJ8eGjiX9mbUWTa/4957sP3zqgCLPCw8m+uQvbjy/3+Wd6R0Xus9jw7GFmxJpOauc23/IyWtxycQw4k2OfNyhEzyobbOGPnVXsLz8/CdZupwLw8Cu8u7848eGcQeIxkEeoR8gaB9pttiOF8q+/uuKB1jmXsSGw5bs5oeGof/fsQ0sr/yK67szTczJytuQAVIuNmqwBK4mp3mIPZGbZo00z/3Jla9I/IsztcDRx5taOpPD461GzpAedfphnGeHTSBjHCYVI/xVb8=We’ll come back to the suspect you ID’d later in this activity, so you can see if you’re right.

6.3.3 Identify the Claim

Consider the discussion of eyewitness identification so far, as well as the video you just watched.

Question 6.1

sz0KcvBNE6qKMLimYjyiIQm/meUVx6eo6V9gKHkrh1p7TYoTyZ//qIOfutj/6e1NZtrsrJW2EolEbvADdU0l77C3ToHaUigtFfww+DcRjC+biFRkZAttrEJbY1ZW5hVCPYZNJkyz7kkppW20V/CVM7N+Pi5F7BeUGr+EPW01bp/C+2aTLFjLLUj+XbOuX0x2aN4lyhXDZ4Itg49CFCTCi5vTaYdltkppuimP++w2Sb3LU09drDGVtYaC2MeztSTgp39Ap2RIGB5GFNPAPwtcLH2tIsUVXdu81pksdNbdfEuNsMIVgha+eFtqpzB7BNu4tDAUSQ2xeoMd5L8ck19tpruMvoxUZzyM6u7tPelSUcfSr6skKxGUF4sw9ox3Y31zYusmOxSSTTqnOv0wfaqVHPQqnINAg08ik1W9ILhKTAfl5j16Y7hkxOs8RTLz3yIDir90pF2T770jVCDJzVjPMChazi2EhgMS3zJV0I/7dfILtO4MBKhdUAiPUcCFgnCJ2Qa3tBRF13Mcib5iReQ/3q16TO6/79jInnSBzLmzieBz0IiJFqz/tBYltJb3uYdBGMM6HUfAIEtptZojwSRmaCF1Jd6lKFiEJWkvLp9NSz1QY/FS2eBQdLtzODyLKk3jG0QwimwqPzBZAU+/AiXJvcW25B96d5THXkoFEDcRYdy52WZoYHempDwxiDCnvF2Syd8QAwwvCdNVa0/qKYwsVNuZkeDQZsSWcejX7v8y7jE/eJmV4tzFmDC2I0sRY/Xr1UkIuxio4UX2332l8xv11pNcMJyOLNTDvjzGtyPAeu71Cahf0ohLOuHEBNHgppZ0qeIv0hoeQwa6Rvv8pzprXzfz8DN5E5bX0ocLvVnJQjSKDVQ46.4 Evaluate the Evidence

2

Evaluate the Evidence

6.4.1 Testing the Claim

The hypothesis—the claim that eyewitness identification is typically accurate—has been tested many times by psychology researchers. And this is a case where the verdict is clear. Eyewitness identification is notoriously unreliable (Loftus, 2013). We know this in part because more than 300 people who had been convicted based on eyewitness testimony were later found innocent based on DNA evidence (Innocence Project, n.d.).

As just one example, Larry Fuller (pictured below) was identified as a rapist by an eyewitness. Fuller had a full beard, and the eyewitness originally said that the rapist had no facial hair (Justice Project, 2007). You can’t grow a full beard in a matter of hours or days! Still, this eyewitness identification was used to convict Fuller. In 2006, after 18 years in prison, Fuller was finally exonerated and released based on DNA evidence.

6.4.2 Research on Eyewitness Memory

Now let’s look at the psychological research on the problems with eyewitness memory. Psychology researchers have looked at how the misinformation effect can affect an eyewitness’ memory (Frenda & others, 2011). They also have examined how racial biases affect our ability to identify people accurately; specifically, people tend to misidentify people of other races more than people of their own race (Wells & Olsen, 2001). Further, some researchers have also taken a step back from the memory part of being an eyewitness, and have asked how well we encode information about people’s faces in the first place (Megreya & Burton, 2008). We’ll explore this face encoding study in more detail.

6.4.3 Identifying Faces, Part I

In this study, researchers tested participants’ ability to accurately identify someone without any time lag (Megreya & Burton, 2008). As the researchers put it, they wanted to test “eyewitness memory (without the memory).” They thought this would provide a baseline of the absolute best that people could do with eyewitness identification by removing the impact of time and memory on the identification.

The researchers showed their participants, university students in Egypt, a series of photos of men. Each time, the photo was accompanied by ten other photos. Half of the time, there was a different photo of the man from the original photo. Half of the time, the man from the original photo was not in the photo array at all. Try it for yourself. Look at the man in the top photo here. He may or may not be in the array of ten photos below it. Below the photo array, click the number of the photo that matches him, or the option that says “He’s not here.”

Question 6.2

nOkyfec61lraS5C8frESAOlUYfjlKRu/35lazhLaTpMuxi9+p/L84Lz2uWP3QBXHx7dvg0a1NdikCehc0qpNxVY3QIbqzbhtO6lPu1k7+tedzmkvm5NfMNmmK/+S0ycvYsV06EMWcg0V5YvZkYr5CFuhg5ej7+O2EbOZMr/ZaaXtRx1TfsqZMo2JScVtnb+rl1EPP0Lcf5d1Hmw/s2vVTLN1l6thTnCiOuORpZ1KKG8RDSdloN6scss6mNcX2VM6uzbJPTz4dzO3vJRsGtHrjjGv3rU=6.4.4 Identifying Faces, Part II

Let’s first think about this experiment, and then think about what we predict the outcome to be.

Question 6.3

ir0QzuKGpE5j4BXTlwhPaX+3XoWWCGi4hEsaeQibCEFqz3Ik67Xc19mDd4SBSvGEjiF0N/pOdNWhXS/EecEJnGXGv9K7sR/K79AvxTpxsst707qdYeUDCeEABVzNlsPepRTCBlCT3XGTcbA0y1eeVRmM8AJvFoHC7XiMCDhCcLc1jJGWD2I9y0fkBlwhc3zdX6ogT6r7VqlnP9qawxJpNdcmz8kChl2fDo596xru5FIfJlNGDFK4WqL4te0yh3JOaU3Npe+KEzz97d8OSrcb+bLPypQyvnelhqSVPVsRCMfZYd2JUxdd9CwP7sYArrmmh5QGyT9Y+akKdBR8V9v4xHtF5KASdQeu6w6ZIvgggBBxL+vg/gCdVYjcY7ZZVGNa9tFPcsms3//VdQ6glCXT9WtaHXk/jDEa3QCIVzXV6CRjbt6FYrgyNnhov1P2FOhLjJ4wv81CsHBkNCChYufJEyFERZ5WLTz7kR9PLzR8ciJpzgV9Qd+No/7r1DeYf80SuL+ru2lhwpQ6hwZpWHhJII2n/pcoP+9hGjAHNHyIYkC+QFzRDozLtaUgNms=Question 6.4

/DZGb7eYYLXXroU8C9Wgvg+1L+9V7/hiCzs0nVpRoTODJh7KTDzT/NmHA/nFsRXaXmTAqBqz+3kPSLe6T0Hgn37fnNph5Dr86NfVcMX0QQThJ3cg1SXGO2vVViLLhzUckxUcQ+g9NFQ/dXYCkz5gvxiYLY7COG4MkCzMFjXwJ8pI7vYKV+yka1zHRRZLhYfrdxZSWDjVJ0h0dFN/ckAiy/AhZWVHRSdenfH7nMZwgrm+xBmUWNDuG8SUxr38osmcibATQ2R5wzUWqgevsMVBLdDKfmcp0oT8akAzDbB9kNNiFXRJkUYmmJbDCUm3brFsNYBy5aPJVJWjanpOqmfO1XgMCBQZTo3Hfz/qLTXNJxsd3U1WL/ifoIZmUl0sHpkQs27LI/T9WNwThcQ9oMz+vbCy5aE+09LvWnu9empaRIZFuaiRsHZark12qTeyOYgrWaaJszVeFn3IDNH6ZVO5QxA82G2fl8skCpeEiQV1m6lOSJqPKXSzH2scLnRiWGMNeaY58g==6.4.5 Recognizing the Suspect, Part I

In the study we’re discussing, participants didn’t even need to hold a face in their memory in order to identify a person later. They simply needed to look back and forth to figure out who the person is, which seems to be an easy task (Megreya & Burton, 2008). [] The researchers ran this easy identification part of the study to provide a baseline for eyewitness recognition. That is, if eyewitness memory is bad, what is the best we can hope for in terms of simply recognizing a suspect?

%

Question

jlWhMZpwEx08v2H7n3eIfJmWW8knn3eObt3nmfSdPTCx/qGSBJVAa8vBtYRECx032sAjA3PXckuwrvgVBAVe6o/qq345mgDaHq50dWqBVB8kBmjv7eJtZUSMBeAFXA3JUSf6KoQxwCEGpwvA+6RmeWejdg7yVdrFemEgtfuagR+xkVsdbKRvQO86q2e6IgiS/X3Juim655H1nuXSbcSsJRwnJhrqeiUWUy2B8SqPmxiH6mmDfHBgvgs/lhguLXGlJcKIoMbiqwdReuWy8EOUujcEkrM=6.4.6 Recognizing the Suspect, Part II

In the previous screen, you estimated that people would accurately match the target with the correct photo NO RESPONSE ENTERED of the time. In the actual study, even with this apparently simple task, participants were only a little over 66% accurate. Accuracy rates were similar in both conditions—when there was a matching photo below and when there was not. And even when researchers had the actual person stand there—live—alongside the ten photos, the accuracy rates were no better! As the researchers put it, “matching images of unfamiliar faces is a difficult task” (Megreya & Burton, 2008). So, rather than set a baseline against which the memory part of eyewitness identification could be judged, these researchers discovered a new problem: Simply encoding the face of the perpetrator isn’t easy!

6.4.7 The Many Stages of Eyewitness Identification

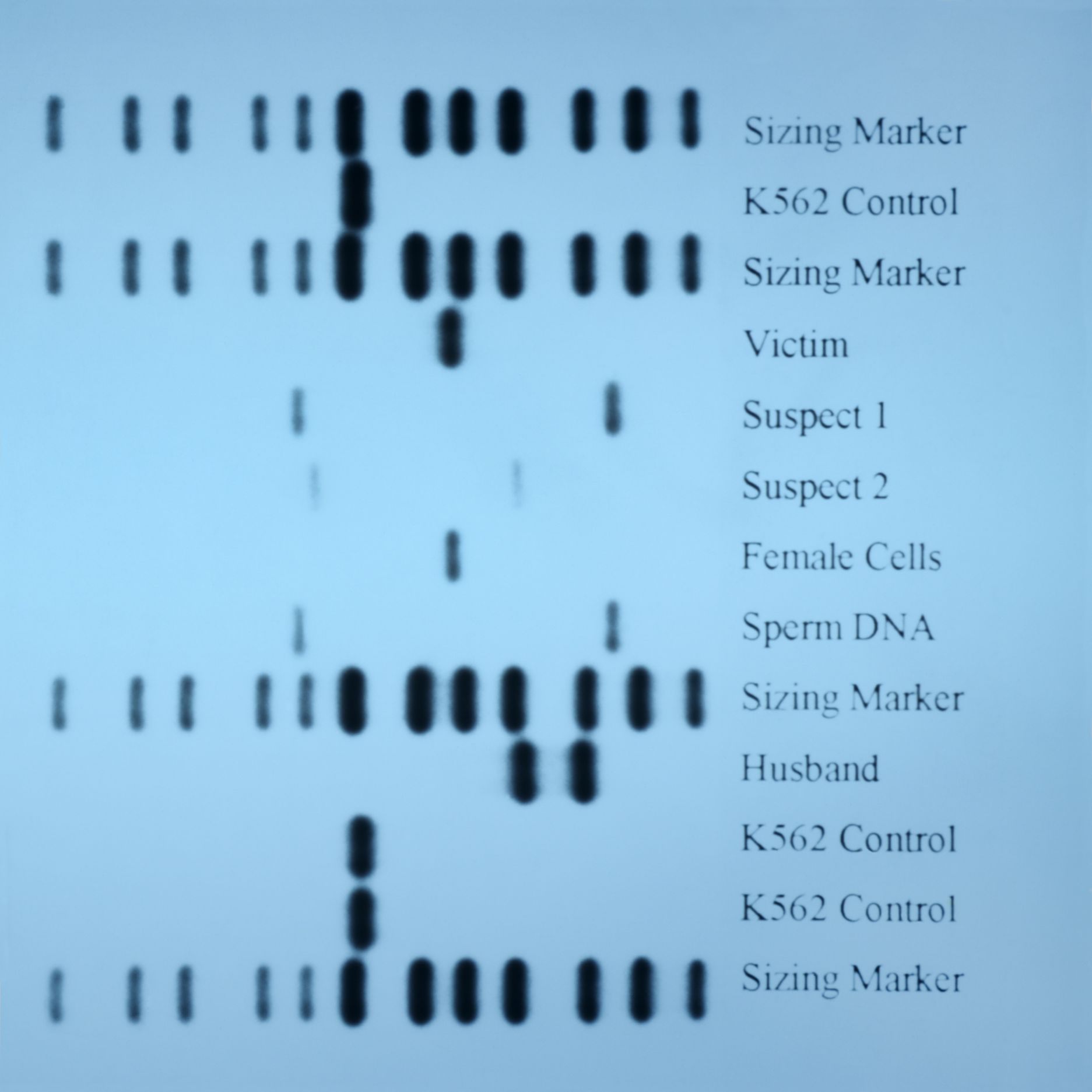

Identifying a perpetrator is complicated. The first step is simply encoding the details of the person’s face and then picking out the same face in a different context. But as you now know, people get that right less than two-thirds of the time. So how accurate are people when there is a time lag in eyewitness memory or factors such as misinformation, which can alter even a correct memory? Psychology researchers have demonstrated overwhelmingly and convincingly that eyewitness identification is fraught with the potential for error. And DNA testing (pictured below) has confirmed these errors hundreds of times. However, the different types of psychology research suggest several alternative explanations for the problem of eyewitness misidentification. In the next section, we’ll talk about some of these alternative explanations.

6.5 Consider Alternative Explanations

3

Consider Alternative Explanations

6.5.1 Eyewitness Memory

There is a great deal of research that shows that eyewitness misidentification results from problems with memory (Loftus, 2013). But as you saw from the previous study, there are alternative explanations for why eyewitness misidentification occurs so often. One explanation is that people can have trouble encoding the details of faces in the first place. If people can’t encode the information, even when they are trying to, then how can anybody accurately identify a criminal after a time lapse?

But there’s another alternative explanation: It depends on how well the eyewitness is paying attention when the crime is being committed. Let’s return to the crime you witnessed earlier in the video. You looked at an array of ten photos of suspects, and you choseNo responsed entered.

In the next screen, you’ll see how you did.

6.5.2 Whodunnit?

[]

Remember, there was a group of volunteers in the pub watching the same fatal stabbing that you saw on the video. Let’s see how they did!

So, none of the live witnesses picked the actual murderer! And only one of them even placed him in the pub at the time of the murder.

6.5.3 Misidentification

Were you surprised at how poorly people, as a group, tend to do at identifying a suspect? It’s likely that, overall, the students in your class are doing just as poorly as the volunteers in the pub. More than 100 introductory psychology students watched the same video you did, and just 10.2% of them chose the correct suspect—suspect number 1. That is exactly what would happen if they just guessed with their eyes closed! Yet, about 20% chose suspect 2 who wasn’t even in the pub at the time of the murder. And about another 20% chose suspect 8—the victim! Based on these results, the police might have arrested the wrong suspect. They couldn’t have targeted the dead victim (number 8), but they may have gone after suspect number 2. Why aren’t people much better than chance, or just guessing, when they identify a suspect that they saw briefly? We’ll explore that next.

6.5.4 Why We Misidentify

Just by chance, about 10% of people doing this activity will be correct and the remaining 90% will be wrong. And that’s what we found with the introductory psychology students. Surprisingly, most people don’t do much better than chance at identifying the correct perpetrator. The majority of students who watch this video will likely misidentify the murderer, as did the introductory psychology students and most of the volunteers (who saw it live). What’s scary is that, in real life, this eyewitness evidence could be used to convict a suspect, even if he or she is innocent. Remember, in the video clip you watched earlier, two of the volunteers picked suspect 2 (as did about 20% of the introductory psychology students), and suspect 2 wasn’t even present at the crime!

Based on the discussion within this activity, which of the following are possible reasons for the misidentification? Click all that apply.

Question 6.5

6huFohHnI6aqmMKcVLljBNgorvk= Problems with memory

6huFohHnI6aqmMKcVLljBNgorvk= Problems encoding the face

6huFohHnI6aqmMKcVLljBNgorvk= Problems with paying attention

6.6 Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

6.6.1 Science vs. Law

The case of eyewitness testimony offers an interesting contrast in sources. Remember the quote from William Brennan (pictured below)? “There is almost nothing more convincing [to a jury] than a live human being who takes the stand, points a finger at the defendant, and says 'That's the one!’” Turns out Brennan said that when making an argument that eyewitness testimony is problematic. In fact, he found eyewitness testimony problematic because it is so convincing, and people don’t realize its flaws. Unfortunately, Brennan is in the minority. For the most part, the legal system has prevented experts on eyewitness testimony from speaking about these problems at trial (Loftus, 2013). To figure out why, let’s examine the two sides—the law and the psychological science.

![This is a photo of William Brennan who stated that “There is almost nothing more convincing [to a jury] than a live human being who takes the stand, points a finger at the defendant, and says 'That is the one!’“](asset/ch6/images/TLS6UN8_56481964.jpg)

6.6.2 Psychological Science in the Courtroom

The most famous researcher of eyewitness testimony is Elizabeth Loftus (pictured below). She recently summarized the history of the relationship among psychology, law, and eyewitness testimony (Loftus, 2013). Before the 1980s, she notes, expert psychologists were barred from sharing research in the courtroom out of fear that it might interfere with the juries’ decisions. The legal system and the general public were skeptical of psychological science as a source. Eventually, several higher courts (including the Supreme Court) started reversing verdicts if an expert on eyewitness testimony was excluded from the trial. The arrival of DNA evidence bolstered these higher court decisions. Three-quarters of cases that have been overturned by new DNA evidence were originally based on eyewitness misidentification.

6.6.3 Psychology and Law Now

Now, psychological research on eyewitness identification is mostly accepted by the court, but there are still misconceptions among the general public (Loftus, 2013). People continue to be convinced by one person pointing the finger at another. To help reduce eyewitness misidentification, the Innocence Project encourages techniques that psychological science has shown will reduce eyewitness misidentification before a jury hears any testimony in court (Loftus, 2013). The techniques are listed below. See if you can drag-and-drop each technique (in blue) to match it to its correct explanation.

The law increasingly bases its eyewitness policies on psychological research. Hopefully, information from both sources will convince the general public that eyewitness misidentification is real, but its occurrence can be reduced by the techniques listed here.

6.7 Assessment

Assessment