Chapter 2. The Right Brain Versus the Left Brain

2.1 Welcome

Think Like a Scientist

The Right Brain Versus the Left Brain

By:

Susan A. Nolan, Seton Hall University

Sandra E. Hockenbury

REFERENCES

Allen, Daniel N.; Strauss, Gregory P.; Kemtes, Karen A.; & Goldstein, Gerald. (2007). Hemispheric contributions to nonverbal abstract reasoning and problem solving. Neuropsychology, 21, 713—720.

Aziz-Zadeh, Lisa; S.-L. Liew, Sook-Lei; & Dandekar, Francesco. (2013). Exploring the neural correlates of visual creativity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8, 475—480. doi:10.1093/scan/nss021

Gazzaniga, Michael S. (2005). Forty-five years of split-brain research and still going strong. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6, 653—659.

Goswami, Usha. (2006). Neuroscience and education: From research to practice? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7, 406—413.

Nielsen, Jared A.; Zielinski, Brandon A.; Ferguson, Michael A.; Lainhart, Janet E.; & Anderson, Jeffrey S. (2013). An evaluation of the left-brain vs. right-brain hypothesis with resting state functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging. PLOS ONE, 8, e71275. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071275

Springer, Sally P., & Deutsch, Georg. (2001). Left brain, right brain: Perspectives from cognitive neuroscience. (5th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman/Worth Publishers.

FAQ

What is Think Like a Scientist?Think Like a Scientist is a digital activity designed to help you develop your scientific thinking skills. Each activity places you in a different, real-world scenario, asking you to think critically about a specific claim.

Can instructors track your progress in Think Like a Scientist? Scores from the five-question assessments at the end of each activity can be reported to your instructor. To ensure your privacy while participating in non-assessment features, which can include pseudoscientific quizzes or games, no other student response is saved or reported.

How is Think Like a Scientist aligned with the APA Guidelines 2.0? The American Psychological Association’s “Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major” provides a set of learning goals for students. Think Like a Scientist addresses several of these goals, although it is specifically designed to develop skills from APA Goal 2: Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking. “The Right Brain Versus the Left Brain” covers many outcomes, including:

- Use scientific reasoning to interpret psychological phenomena: Use psychology concepts to explain personal experiences and recognize the potential for flaws in behavioral explanations based on simplistic, personal theories [explore evidence that we’re either “right-brained” or “left-brained”]

- Demonstrate psychology information literacy: Describe what kinds of additional information beyond personal experience are acceptable in developing behavioral explanations [identify common pseudoscience strategies]

2.2 Introduction

This activity invites you to test the claim that people can be "right-brained" or "left-brained." First, you’ll take a quiz that is similar to many of the right-brained/left-brained quizzes that you can find online. You will then consider evidence from research on brain activity to explore the question of whether people are left-brained or right-brained. You’ll consider alternative explanations for the reasons many of us believe that people can be left-brained or right-brained. And you’ll explore questions about the source of online quizzes claiming that they can sort us into right-brained people and left-brained people.

2.3 Identify the Claim

1

Identify the Claim

2.3.1 Are You Right-Brained or Left-Brained?

Have you seen online quizzes that claim to determine whether you are left-brained or right-brained? The assumption behind these quizzes is that left-brained people are rational and analytical, and right-brained people are creative and artistic. The results of such tests are being used in real-life situations. For example, some elementary school teachers have been encouraged to test their students to determine whether they are left-brained or right-brained. There are even courses designed to help teachers adjust their teaching styles to fit the children in each category (Goswami, 2006).

What do we learn from right-brained/left-brained assessments? We’ll explore the evidence, but first, look over this mock Web site, which is similar to many right-brain/left-brain quiz sites online. (You can click the image to enlarge.) On the next screen, you can take the quiz advertised on this site.

2.3.2 Take the Mock Quiz

Imagine you are intrigued by the Web site you just viewed, and you want to take the advertised quiz. The mock quiz below was developed from actual quizzes available online, and you can try it now. You must complete all 17 questions in this mock quiz in order to receive your “right-brain/left-brain results” and advance to the next screen of the Think Like a Scientist activity. (Have fun with this quiz! Your answers will not be recorded and will not be reported to your instructor.)

Question

1. Look at the ground and close one eye. Which eye is still open?

| A. |

| B. |

2.3.3 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

2. Which of the following images best expresses the theme ‘community’?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.4 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

3. You’ve lost your sunglasses at school. How do you go about finding them?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.5 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

4. How do you choose what to watch on TV?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.6 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

5. You go to a networking event and meet some new people. What do you remember about them the next day?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.7 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

6. When coloring in coloring books as a child, did you:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.8 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

7. Doodling in the margins:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.9 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

8. You are planning a road trip with friends. Do you:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.10 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

9. Which subject came more easily to you in elementary school?

| A. |

| B. |

2.3.11 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

10. When someone asks you a tough question, do you automatically look:

| A. |

| B. |

2.3.12 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

11. Look at the image above. Which of the images below is most similar to it?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.13 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

12. When you get lost, you prefer to:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.14 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

13. Do you believe that there is a right answer to every question?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.15 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

14. Can you listen to music and read for comprehension at the same time?

| A. |

| B. |

2.3.16 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

15. Do you believe in serendipity?

| A. |

| B. |

2.3.17 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

16. Do you communicate more effectively through writing or conversation?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.18 Take the Mock Quiz

Question

17. Which of these shapes is most appealing to you?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

2.3.19 What Would It Mean to Be Right-Brained or Left-Brained?

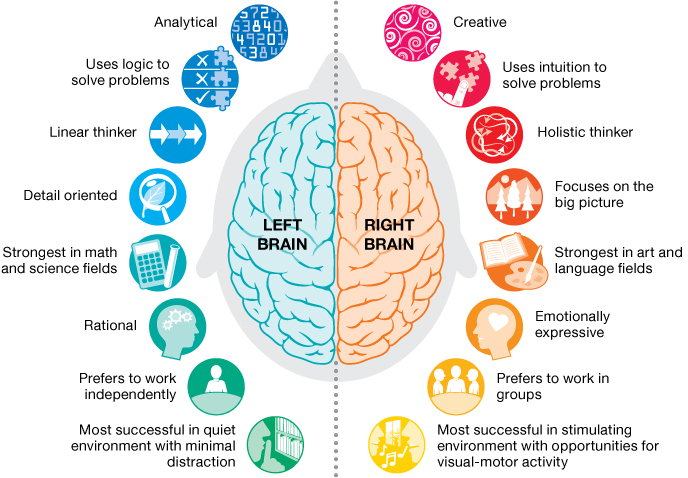

What would it mean to be “right-brained,” “left-brained,” or “balanced”? Quizzes like the one you just took work to sort us into categories, which are associated with a set of characteristics. Knowing what category we fit in will supposedly help us identify a range of fundamental information about ourselves. For example, this image, developed from infographics available online, claims to list the specific differences between “right-brained” people and “left-brained” people. As you can see, “left-brained” people are said to be analytical and linear in their thinking, whereas “right-brained” people are viewed as intuitive and holistic.

Question

In general terms, what are the claims that the right-brain/left-brain quiz sites and infographics are making?

2.4 Evaluate the Evidence

2

Evaluate the Evidence

2.4.1 The Interconnected Brain

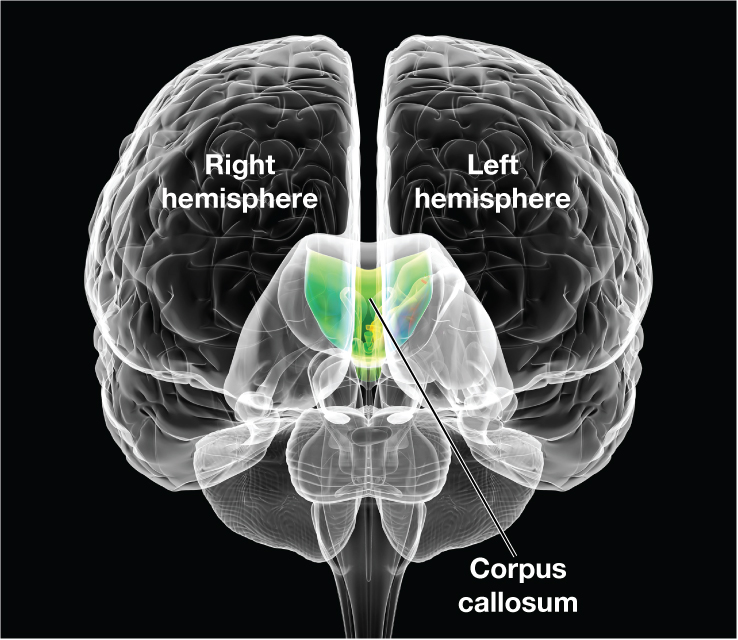

As you learned when reading the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter in your textbook, the “right brain”—or right hemisphere—and the “left brain”—or left hemisphere – are very much interconnected. They work together, via the corpus callosum, to help us speak, think, learn, and get through our days (see Allen & others, 2007). So unless the corpus callosum has been surgically sliced or otherwise damaged, the two hemispheres of our brains are always functioning in an integrated fashion.

2.4.2 Is Designating Someone as Right-Brained Versus Left-Brained Really Valid?

Brain scan research shows the brain’s integrated functioning. A comparison of fMRI scans of the brains of more than one thousand individuals found that, as expected, certain functions were lateralized, like language. But there was no difference among individuals in terms of preferentially relying on networks in the left hemisphere versus the right hemisphere (Nielsen & others, 2013). The researchers concluded that, as a whole, “an individual brain is not ‘left-brained’ or ‘right-brained.’”

In the intact brain, both hemispheres are always working together. So it’s simply not possible to identify a “side” that is somehow responsible for personality traits or complex behaviors. There is no evidence, for example, that the right hemisphere is more creative, intuitive, or artistic than the left (see Gazzaniga, 2005). In fact, despite the widespread belief that “right-brained” people are the creative ones, researchers found that when a task required a creative solution, there was more activation in the left hemisphere than when a task required a noncreative solution (Aziz-Zadeh & others, 2013).

2.4.3 Right-Brained Versus Left-Brained Teaching

Think again about the claim that teachers should categorize their students as right-brained or left-brained in order to know how best to teach them. If the two hemispheres of our brain do not function independently, how can we seek to influence or communicate with only one at a time? There is no evidence that teachers are even capable of teaching just one side of the brain, never mind whether it would make a difference if they could. Education researcher Usha Goswami (2006) calls the idea that you could develop left-brained and right-brained educational techniques a “neuromyth.”

2.5 Consider Alternative Explanations

3

Consider Alternative Explanations

2.5.1 Why Do We Believe “Neuromyths”?

You already knew that the evidence suggested that we are not either “right-brained” or “left-brained.” After all, this is covered in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter. What isn’t discussed is why so many people believe “neuromyths” like this. When a claim contradicts accepted scientific understanding, it’s time to think like a scientist and consider alternative explanations.

When we hear that people tend either to be right-hemisphere-dominant or left-hemisphere-dominant, it seems to makes sense. We know people who are more creative and we know others who are more analytical, so we can imagine that this difference might be grounded in our brains. Several pseudoscience strategies at work here, all described in the chapter on Introduction and Research Methods, help these claims to seem reasonable.

2.5.2 Pseudoscience Strategies

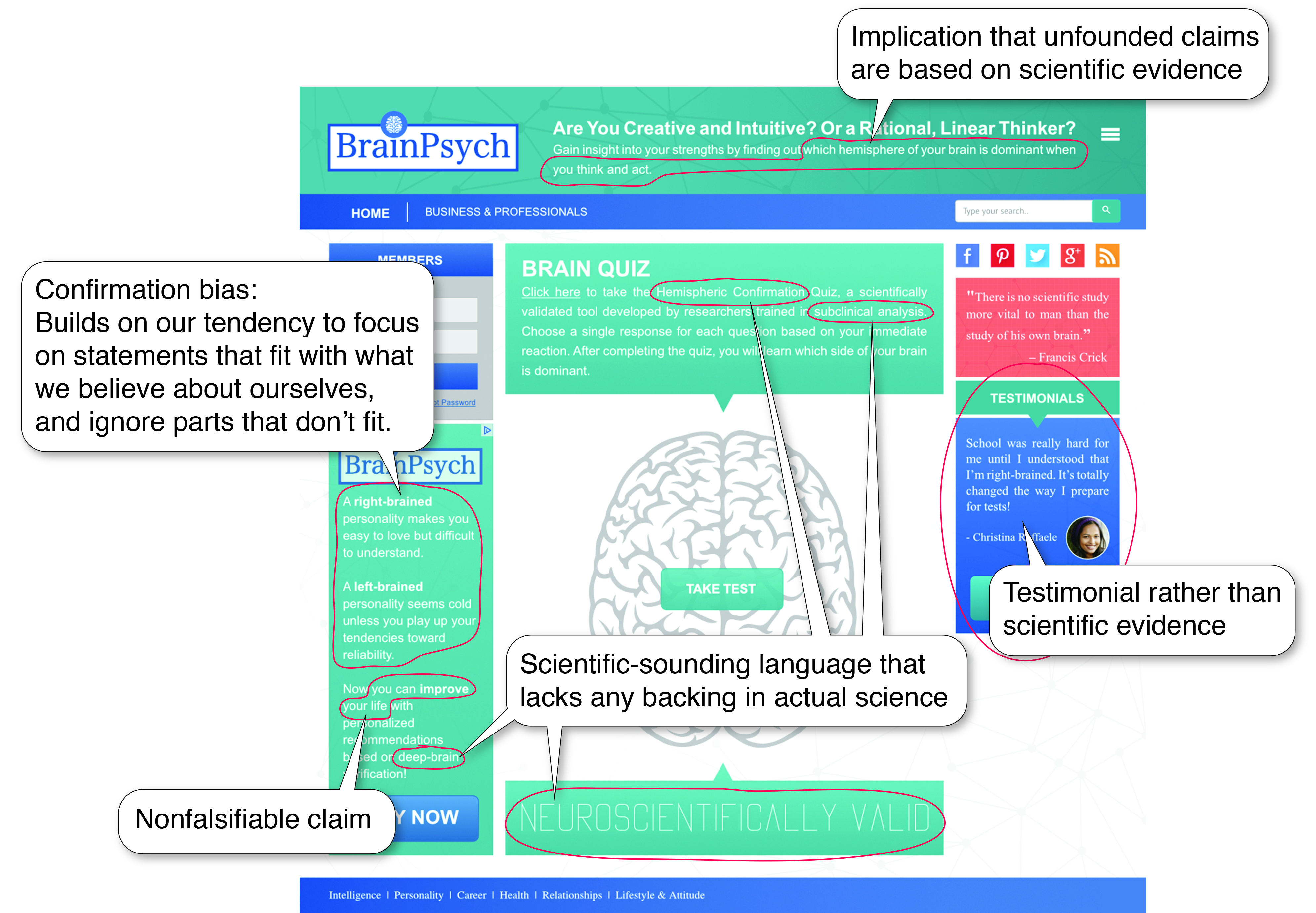

The power of pseudoscience is that it seems scientific. There are several pseudoscience strategies that may be responsible for our incorrect beliefs that we are “left-brained” or “right-brained.” In the Science Versus Pseudoscience box in the Introduction and Research Methods chapter, “What Is a Pseudoscience?”, you learned seven strategies that are often used to make pseudoscientific claims seem scientific. Let’s look at how the mock Web site that you saw earlier in this activity uses four of these strategies.

Through various pseudoscience strategies, a claim can be made to sound convincing, even when it contradicts solid scientific evidence. The result? Obvious neuromyths remain appealing.

2.6 Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

4

Consider the Source of the Research or Claim

2.6.1 Where Do Right-Brain/Left-Brain Quizzes Come From?

Our tendency to believe “neuromyths” is compounded by information that we get online. Google “Am I right-brained or left-brained?” Click on a couple of the links.

Now think about the results of your search. Did it pull up any right-brain/left-brain quizzes? What kinds of organizations are associated with these tests online?

Question

Look at one of the Web sites that you found. Which of the following are true? Click as many as are accurate. The Web site:

| was established by a research or educational organization. | |

| was established by a for-profit business. | |

| provides opportunities to purchase products or information. | |

| provides information on how the test was developed. |

2.6.2 Red Flags in Online Quizzes

Quizzes that claim to determine if you are “left-brained” or “right-brained” are just the tip of the iceberg in online psychology testing. There are quizzes that claim to classify your personality as Type A or Type B, to determine your ideal romantic partner, and to identify the careers in which you would be most successful. And like the right-brain/left-brain quizzes, most tests you find online are not grounded in science.

So, what should you be looking for to determine if a quiz is scientifically supported?

Remember that the mock Web site we examined earlier contains no real information about how the quiz was developed. Instead, the site offers only vague information such as “scientifically validated” and a quote from a well-known scientist to give it an air of legitimacy. These are the main red flags indicating a quiz might be pseudoscientific.

2.6.3 Finding Scientific Psychology Quizzes Online

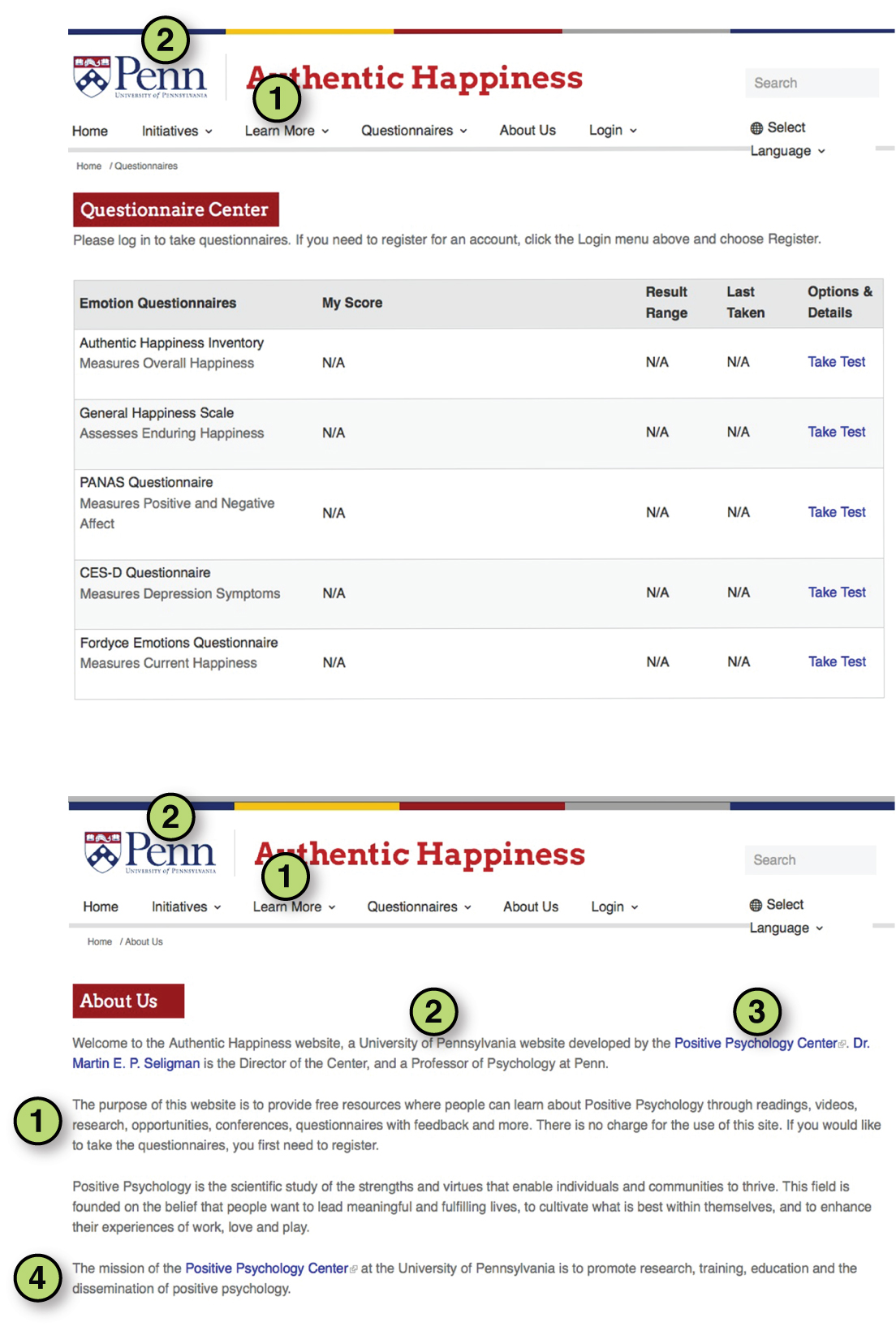

So what indicates that a quiz is scientific? Look at the screenshot below of a Web site that offers assessments to measure your emotions. Below that is a second screenshot of the “About Us” information from this site. You will notice several signs that indicate a more scientific approach to psychological measurement. Among these are:

- Indications that the measures on this site are grounded in science, including links under the “Learn More” heading leading to resources such as peer-reviewed journal articles

- A university affiliation

- The involvement of an academic psychologist

- A clear science-based mission statement

2.6.4 Are Online Psychology Quizzes Useful or Merely Entertainment?

Earlier in this activity, our pseudoscientific quiz told you that [INSERT STATEMENT BASED ON STUDENT’S QUIZ RESULTS FROM SCREEN 5: you tend to be more left-brained. OR you tend to be more right-brained. OR you tend to be balanced, using both sides of your brain equally.] Based on what you’ve learned in this activity, you now know that this result is not based on real science about the brain and is not valid information. Tests like this can be fun, but don’t actually tell us anything useful.

When you encounter a psychology-related survey or assessment online, think about your psychology course and ask yourself if the science makes sense. When a test cannot be valid, it cannot provide you with any useful information.

2.6.5 Finding the Best Test

If you’re not sure about the science behind an online psychology test, look for clues on the Web site. Is it an unaffiliated organization with no clear scientific rationale for its claims? Or is it a scientific or educational organization, such as a university? Is a psychologist involved? What is her or his background?

And finally, even the best, most scientifically developed measure can’t tell you everything about yourself. Don’t put too much weight on the outcomes of any single assessment, even if it’s a good one. You’re much more than a single score!

2.7 Assessment

Assessment

2.7.1 Assessment

Question

Which of the following is TRUE about differences between the left and right cerebral hemispheres?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |