Understanding Digital Media

Chapter Opener

48

go multimodal

Understanding Digital Media

Schools, businesses, and professional organizations are finding innovative uses for new media tools and services such as blogs, wikis, digital video, Web-

Plotting Flickr and Twitter locations in Europe produces this luminous map of the continent, suggesting the sweep of new media activity.

Eric Fischer.

Choose a media format based on what you hope to accomplish. A decision to compose with digital tools or to work in environments such as Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram should be based on what these media offer you. An electronic tool may support your project in ways that conventional printed texts simply cannot — and that’s the reason to select it. Various media writing options are described in the following table.

| Format | Elements | Purpose | Software Technology/Tools |

| Social networks, blogs | Online discussion postings; interactive; text; images; video; links | Create communities (fan, political, academic); distribute news and information | Facebook; Twitter; Reddit; Blogger; Instagram; Tumblr; WordPress |

| Web sites | Web- |

Compile and distribute information; establish presence on Web; sell merchandise, etc. | Dreamweaver; Drupal; WordPress, Google Sites |

| Wikis | Collaboratively authored linked texts and posts; Web- |

Create and edit collaborative documents based on community expertise; distribute and share information | DokuWiki; MediaWiki; Tiki Wiki |

| Podcasts, music | Digital file- |

Distribute mainly audio texts; document or archive audio texts and performances | Audacity; GarageBand |

| Maps | Interactive image maps; text; data; images; mind maps | Give spatial or geographical dimension to data, texts, ideas; help users locate or visualize information | iMapBuilder; Google Earth; Google Maps; NovaMind |

| Video | Recorded images; live- |

Record events; provide visual documentation; create presentations; furnish instructions, etc. | Animoto; Camtasia; iMovie; Movie Maker; Blender; Soundslides |

Use social networks and blogs to create communities. You know, of course, that Facebook and Twitter have transformed the way people share their lives and ideas. Social networks such as these are vastly more interactive versions of the online exchanges hosted by groups or individuals on blogs — which typically focus on topics such as politics, news, sports, technology, and entertainment. Social networks and blogs integrate comments, images, videos, and links in various ways; they are constantly updated, most are searchable, and some are archived.

College courses might use social networks and blogs to spur discussion of class materials, to distribute information, and to document research activities: Students in courses often set up their own social media groups. When networking or blogging is part of a course assignment, understand the ground rules. Instructors often require a defined number of postings/comments of a specific length. Participate regularly by reading and commenting on other students’ posts; by making substantive comments of your own on the assigned topic; and by contributing relevant images, videos, and links.

Keep your academic postings focused, title them descriptively, and make sure they reflect the style of the course — most likely informal, but not quite as colloquial as public online groups. Pay attention to grammar and mechanics too. Avoid the vitriol you may encounter on national sites: Remember that anyone — from your mother to a future employer — might read your remarks.

Create Web sites to share information. Not long ago, building Web sites was at the leading edge of technological savvy in the classroom. Today, social networks, blogs, and wikis are far more efficient vehicles for academic communication. Still, Web sites remain useful because of their capacity to organize large amounts of text and information online. A Web site you create for a course might report research findings or provide a portal to information on a complex topic.

This masthead appears on a Web site created by a college professor for his students and colleagues at McDaniel College in Maryland.

Dr. Paul Muhlhauser, McDaniel College, English Department.

When creating a site with multiple pages, plan early on how to organize that information; the structure will depend on your purpose and audience. A simple site with sequential information (e.g., a photo-

Use wikis to collaborate with others. If you have ever looked at Wikipedia, you know what a wiki does: It enables a group to collaborate on the development of an ongoing online project — from a comprehensive encyclopedia to focused databases on just about any imaginable topic. Such an effort combines the knowledge of all its contributors, ideally making the whole greater than its parts.

In academic courses, instructors may ask class members to publish articles on an existing wiki — in which case you should read the site guidelines, examine its current entries and templates, and then post your item. More likely, though, you will use wiki software to develop a collaborative project for the course itself — bringing together research on a specific academic topic. A wiki might even be used for a service project in which participants gather useful information about nutrition, jobs, or arts opportunities for specific communities.

As always with electronic projects, you need to learn the software — which will involve not only uploading material to the wiki but also editing and developing texts that classmates have already placed there.

Hill Street Studios/Getty Images.

Make videos and podcasts to share information. With most cell phones now equipped with cameras, digital video has become the go-

Podcasts remain a viable option for sharing downloadable audio or video files. Playable on various portable devices from MP3 players to tablets, podcasts are often published in series. Academic podcasts usually need to be scripted and edited. Producing a podcast is a two-

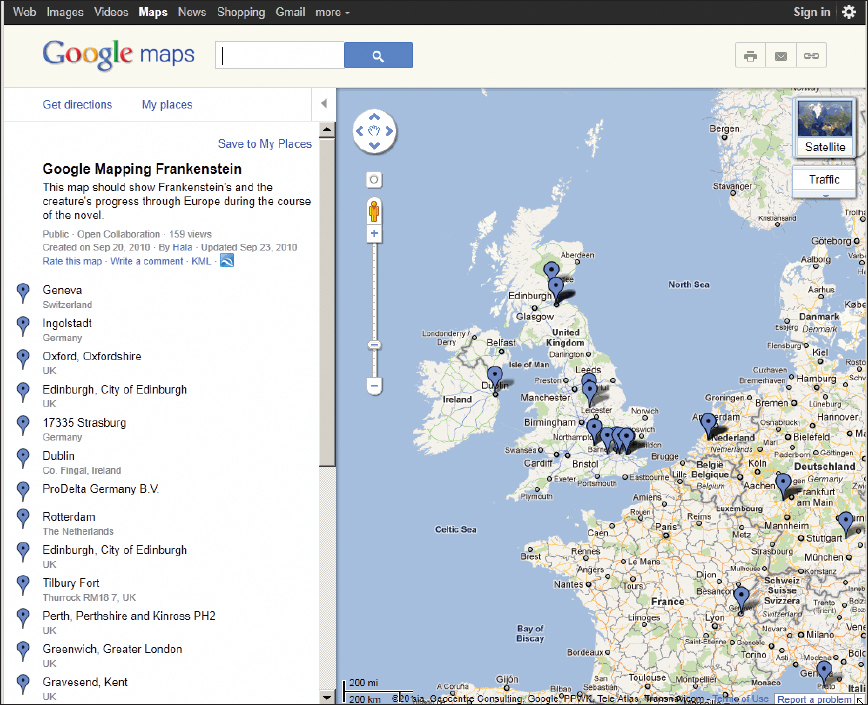

Use maps to position ideas. You use mapping services such as Google Maps whenever you search online for a restaurant, store, or hotel. The service quickly provides maps and directions to available facilities, often embellished with links, information, and images. Not surprisingly, Google Maps, the related Google Earth, and other mapping software are finding classroom applications.

Multimedia maps also make it possible to display information such as economic trends, movements of people, climate data, and other variables graphically and dynamically, using color, text, images, and video/audio clips to emphasize movement and change across space and time. Even literary texts can be mapped so that scholars or readers may track events or characters as they move in real or imaginary landscapes. Mapping thus becomes a vehicle for reporting and sharing information, telling personal stories, revealing trends, exploring causal relationships, or making arguments.

English instructor Hala Herbly asked students to MAP the movements across Europe of the monster from Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein.

© 2010 Google. Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google, Inc., used with permission. MAP data © 2010 Europa Technologies, PPWK. TeleAtlas-

Use appropriate digital formats. Digital documents come in many forms, but you will use familiar word-

Occasionally you need to save digital files in special formats. Sharing a file with someone using an older version of Word or Office may require saving a document in compatibility mode (.doc) rather than the now-

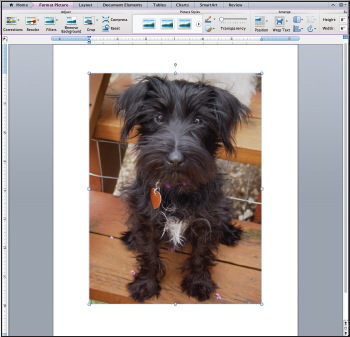

Even if you have only a limited knowledge of differing image file formats (such as JPG, GIF, or TIFF), you probably understand that digital files come in varying sizes. The size of a digital-

For most Web pages and online documents, compressed or lower-

Image-

John J. Ruszkiewicz.

Edit and save digital elements. Nonprint media texts often require as much revising and editing as traditional written ones. In fact, the tools for manipulating video, audio, and still-

Do keep careful tabs on any electronic content you collect for a project. Create a dedicated folder on your desktop, hard drive, or online storage and save each item with a name that will remind you where it came from. Keeping a printed record of images, with more detailed information about copyrights and sources, will pay dividends later, when you are putting your project or paper together and need to give proper credit to contributors.

Respect copyrights. The images you find, whether online or in print, belong to someone. You cannot use someone else’s property — photographs, Web sites, brochures, posters, magazine articles, and so on — for commercial purposes without permission. You may use a reasonable number of images in academic papers, but you must be careful not to go beyond “fair use,” especially for any work you put online. Search the term “academic fair use” online for detailed guidelines. Be prepared, too, to document images in academic research papers.

For a tutorial on photo editing, see Tutorials > Digital Writing > Photo Editing Basics with GIMP

For a tutorial on photo editing, see Tutorials > Digital Writing > Photo Editing Basics with GIMP

For a tutorial on audio editing, see Tutorials > Digital Writing > Audio Editing with Audacity

For a tutorial on audio editing, see Tutorials > Digital Writing > Audio Editing with Audacity