Understanding your audience

Understanding your audience

People like to read stories, so the audiences for narratives are large, diverse, and receptive. Most of these eager readers probably expect narratives to make some point or reveal an insight. They hope to be moved by what they read, learn something from it, or perhaps be amused by it.

You can capitalize on such expectations, using stories to introduce ideas that readers might be less eager to entertain if presented more formally. As Zadie Smith puts it, “A writer hopes to make connections where the lazy eye sees only a chasm of difference.” Women and members of outsider groups have long used narratives to document the adversities they face and to affirm their solidarity. But good stories also cross boundaries and win sympathetic readers from well outside the original target audience.

Of course, you might sometimes decide that the target audience of a narrative is really yourself: You can write about personal experiences to get a handle on them. Even then, be demanding. Think about how your story might sound ten or twenty years from now. Whatever the audience, you have choices to make.

Focus on people. They are what readers care about, so give them names and define their relationships. But don’t slow the action to characterize or describe them. Let your readers figure out the people you are presenting through what they do and say.

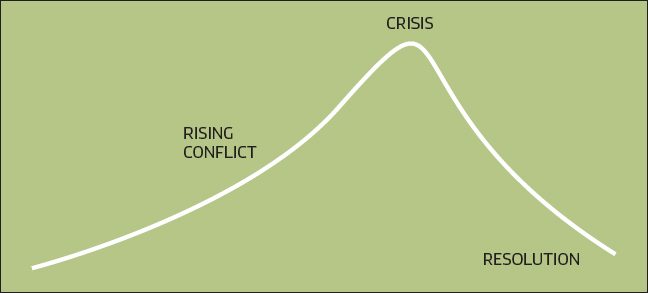

Select events that will keep readers engaged. Which events represent high points in the action or moments that could not logically be omitted? Which are the most intriguing and entertaining? Focus on these and consider cutting the others. Build toward a few major events in the story that support one or two key themes.

Pace the story. After a brisk start, slow the narrative to fill in necessary details about characters and set up expectations for what will follow. If a person plays a role later in the story, introduce him or her briefly in the early paragraphs. If a cat matters, mention the cat. But don’t dwell on incidentals: Keep the story moving.

Adjust your writing to appeal to the intended readers. Here, for example, is a serious anecdote offered in an application to graduate school.

During my third year of Russian, I auditioned for the role of the evil stepsister Anna in a stage production of Zolushka. Although I welcomed the chance to act, I was terrified because I could not pronounce a Russian r. I had tried but was only able to produce an embarrassing sputter. Leading up to the play, I practiced daily with my professor, repeating “ryba” with a pencil in my mouth. When the play opened, I was able to say “Kakoe urodstvo!” with confidence. I had discovered the power to isolate a problem, seek the necessary help, and ultimately solve it. Now I want to pass this power along to others by becoming a Russian language instructor.

— Melissa Miller

But can you imagine Melissa describing her problems with the Russian r differently to her peers, maybe even comically? Such an adjustment would only be natural. And it’s the kind of shift you have to learn to make as well.

A narrative you write for academic readers might need to be as sober and deliberate as Melissa’s statement, and when writing it you might have to keep a tight rein on how you present your life. (refine your tone) But don’t be too cautious. Any story has to have enough grit to make your experiences seem authentic. So pay close attention to how your instructor defines the audience you are supposed to address in a narrative assignment. If need be, ask questions.