Vigorous, Clear, Economical Style

Chapter Opener

34

improve your sentences

Vigorous, Clear, Economical Style

Ordinarily, tips and tricks don’t do much to enhance your skills as a writer. But a few guidelines, applied sensibly, can improve your sentences and paragraphs noticeably — and upgrade your credibility as a writer. You sound more professional and confident when every word and phrase pulls its weight.

Always consider the big picture in applying the following tips: Work with whole pages and paragraphs, not just individual sentences. Remember, too, that these are guidelines, not rules. Ignore them when your good sense suggests a better alternative.

Build sentences around specific and tangible subjects and objects. Scholar Richard Lanham famously advised writers troubled by tangled sentences to ask, “Who is kicking who?” This question expresses the principle that readers shouldn’t have to puzzle over what they read. They are less likely to be confused when they can identify the people or things in a sentence that act upon other people and things. Answering Professor Lanham’s question often leads to stronger verbs and tighter sentences too.

| CONFUSING | Current tax policies necessitate congressional reform if the reoccurrence of a recession is to be avoided. |

| BETTER | Congress needs to reform current tax policies to avoid another recession. |

| CONFUSING | In the Prohibition era, tuning cars enabled the bootleggers to turn ordinary automobiles into speed machines for the transportation of illegal alcohol by simply altering certain components of the cars. |

| BETTER | In the Prohibition era, bootleggers modified their cars to turn them into speed machines for transporting illegal alcohol. |

Both of the confusing sentences here work better with subjects capable of action: Congress and bootleggers. Once identified, these subjects make it easy to simplify the sentences, giving them more power.

Look for opportunities to use specific nouns and noun phrases rather than general ones. This advice depends very much on context. Academic reports and arguments often require broad statements and general terms. But don’t ignore the power and energy of specific words and phrases; they create more memorable images for readers, so they may have more impact.

| GENERAL | SPECIFIC |

| bird | roadrunner |

| cactus | prickly pear |

| lawbreaker | mugger |

| business | pizzeria |

| jeans | 501s |

Don't use words too big for the subject. Don't say "infinitely" when you mean "very"; otherwise, you'll have no word left when you want to talk about something really infinite.

Wolf Suschitzky/Time and Life Pictures/Getty Images.

Many writers are fond of generic terms and the impenetrable phrases they inspire because they sound serious and sophisticated. But such language can be hard to figure out or even suggest a cover-

| ABSTRACT |

All of the separate constituencies at this academic institution must be invited to participate in the decision- |

| BETTER | Faculty, students, and staff at this school must all have a say during this current budget crunch. |

Avoid sprawling phrases. These constructions give readers fits, especially when they thicken, sentence after sentence, like limescale or sludge. Be alert whenever your prose shows any combination of the following features:

Strings of prepositional phrases

Strings of prepositional phrases Verbs turned into nouns via endings such as -ation (implement becomes implementation)

Verbs turned into nouns via endings such as -ation (implement becomes implementation) Lots of articles (the, a)

Lots of articles (the, a) Lots of heavily modified verbals

Lots of heavily modified verbals

Such expressions are not inaccurate or wrong, just tedious. They make readers work hard for no good reason. Fortunately, they are also easy to clean up once you notice the accumulation.

| WORDY | members of the student body at Arizona State |

| BETTER | students at Arizona State |

| WORDY | the producing of products made up of steel |

| BETTER | steel production |

| WORDY | the prioritization of decisions for policies of the student government |

| BETTER | the student government’s priorities |

Avoid sentences with long windups. The more stuff you pile up ahead of the main verb, the more readers have to remember. Very skillful writers can pull off complex sentences of this kind because they know how to build interest and manage clauses. But a safer strategy in academic and professional writing is to get to the point of your sentences quickly. Here’s a sentence from the Internal Revenue Service Web site that keeps readers waiting far too long for a verb. Yet it’s simple to fix once its problem is diagnosed:

| ORIGINAL |

A new scam e- |

| REVISED |

A new scam e- |

Favor simple, active verbs. When a sentence, even a short one, goes off track, consider whether the problem might be a nebulous, strung-

| WORDY VERB PHRASE | We must make a decision soon. |

| BETTER | We must decide soon. |

| WORDY VERB PHRASE | Students are absolutely reliant on federal loans. |

| BETTER | Students need federal loans. |

| WORDY VERB PHRASE | Engineers proceeded to reinforce the levee. |

| BETTER | Engineers reinforced the levee. |

You’ll be a better writer the instant you apply this guideline.

Avoid strings of prepositional phrases. Prepositional phrases are simple structures, consisting of prepositions and their objects and an occasional modifier: from the beginning; under the spreading chestnut tree; between you and me; in the line of duty; over the rainbow. You can’t write much without prepositional phrases. But use more than two or, rarely, three in a row and they drain the energy from a sentence. When that’s the case, try turning the prepositions into more compact modifiers or moving them into different positions within the sentence. Sometimes you may need to revise the sentence even more substantially.

| TOO MANY PHRASES | We stood in line at the observatory on the top of a hill in the mountains to look in a huge telescope at the moons of Saturn. |

| BETTER | We lined up at the mountaintop observatory to view Saturn’s moons through a huge telescope. |

| TOO MANY PHRASES | To help first- |

| BETTER | To help first- |

Don’t repeat key words close together. You can often improve the style of a passage just by making sure you haven’t used a particular word or phrase too often — unless you repeat it deliberately for effect (government of the people, by the people, for the people). Your sentences will sound fresher after you have eliminated pointless repetition; they may also end up shorter.

| REPETITIVE | Students in writing courses are often assigned common readings, which they are expected to read to prepare for various student writing projects. |

| BETTER | Students in writing courses are often assigned common readings to prepare them for projects. |

This is a guideline to apply sensibly: Sometimes for clarity, you must repeat key expressions over and over—

The New Horizons payload is incredibly power efficient, with the instruments collectively drawing only about 28 watts. The payload consists of three optical instruments, two plasma instruments, a dust sensor, and a radio science receiver/radiometer.

— NASA, “New Horizons Spacecraft Ready for Flight”

Avoid doublings. In speech, we tend to repeat ourselves or say things two or three different ways to be sure listeners get the point. Such repetitions are natural, even appreciated. But in writing, the habit of doubling may irritate readers. And it is very much a habit, backed by a long literary tradition comfortable with pairings such as home and hearth, friend and colleague, tried and true, clean and sober, neat and tidy, and so on.

Sometimes, writers will add an extra noun or two to be sure they have covered the bases: colleges and universities, books and articles, ideas and opinions. There may be good reasons for a second (or third) item. But the doubling is often just extra baggage that slows down the train. Leave it at the station.

The same goes for redundant expressions. For the most part, they go unnoticed, except by readers who crawl up walls when someone writes young in age, bold in character, totally dead, basically unhappy, current fashion, empty hole, extremely outraged, later in time, mix together, reply back, and so on. (In each case, the boldfaced words restate what is already obvious.) People precise enough to care about details deserve respect: They land rovers on Mars. Cut the dumb redundancies. (Is dumb unnecessary here?)

Turn clauses into more direct modifiers. If you are fond of that, which, and who clauses, be sure you need them. You can sometimes save a word or two by pulling the modifiers out of the clause and moving them directly ahead of the words they explain. Or you may be able to tighten a sentence just by cutting that, which, or who.

| WORDY | Our football coach, who is nationally renowned, expected a raise. |

| BETTER | Our nationally renowned football coach expected a raise. |

| WORDY | Our football coach, who is nationally renowned and already rich, still expected a raise. |

| BETTER | Our football coach, nationally renowned and already rich, still expected a raise. |

Cut introductory expressions such as it is and there is/are when you can. These slow-

It’s going to rain today.

It was her first Oscar.

There is a tide in the affairs of men.

But don’t default to easy expletives at the beginning of every other sentence. Your prose will suffer. Fortunately, revision is easy.

| WORDY | It is necessary that we reform the housing policies. |

| BETTER | We need to reform the housing policies. |

| WORDY | There were many incentives offered by the company to its sales force. |

| BETTER | The company offered its sales force many incentives. |

Expletives in a sentence often attract other wordy and vague expressions. Then the language swells like a blister. Imagine having to read paragraph after paragraph of prose like the following sentence.

| SLOW | It is quite evident that an argument sociologist Annette Lareau supports is that it is important to find the balance between authoritarian and indulgent styles of parenting because it contributes to successful child development. |

| BETTER | Clearly, sociologist Annette Lareau believes that balancing authoritarian and indulgent styles of parenting contributes to successful child development. |

Vary your sentence lengths and structures. Sentences, like music, have rhythm. If all your sentences run about the same length or rarely vary from a predictable subject-

[Carl] Newman is a singing encyclopedia of pop power. He has identified, cultured, and cloned the most buoyant elements of his favorite Squeeze, Raspberries, Supertramp, and Sparks records, and he’s pretty pathological about making sure there’s something unpredictable and catchy happening in a New Pornographers song every couple of seconds — a stereo flurry of ooohs, an extra beat or two bubbling up unexpectedly.

— Douglas Wolk, “Something to Talk About,” Spin, August 2005

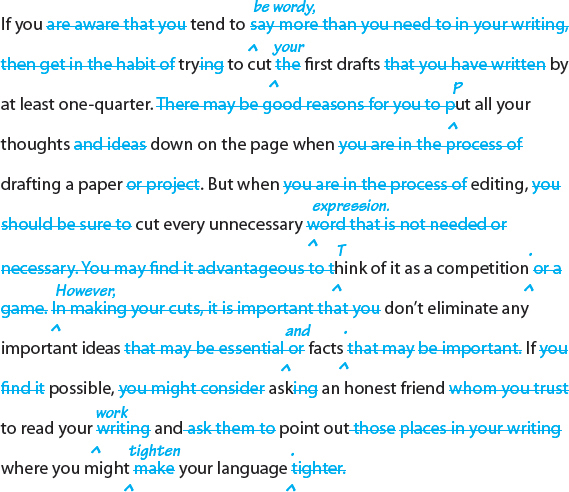

I believe more in the scissors than I do in the pencil.

Roger Higgins/New York World-

Read what you have written aloud. Then fix any words or phrases that cause you to pause or stumble, and rethink sentences that feel awkward — a notoriously vague reaction that should still be taken seriously. Reading drafts aloud is a great way to find problems. After all, if you can’t move smoothly through your own writing, a reader won’t be able to either. Better yet, persuade a friend or roommate to read your draft to you. Take notes.

Understand, though, that prose never sounds quite like spoken language —and thank goodness for that. Accurate transcripts of dialogue are almost unreadable, full of gaps, disconnected phrases, pauses, repetitions, and the occasional obscenity. And yet written language, especially in the middle style, should resemble the human voice, with all its cadences and rhythms pulling readers along, making them want to read more.

Cut a first draft by 25 percent — or more. If you tend to be wordy, try to cut your first drafts by at least one-

For an activity on active and passive voice, see Tutorials > LearningCurve Activities > Active and Passive Voice

For an activity on active and passive voice, see Tutorials > LearningCurve Activities > Active and Passive Voice