Finding Print and Online Sources

Chapter Opener

38

refine your search

Finding Print and Online Sources

When writing an academic paper that requires facts, data, and reputable research or opinion, look to three resources in this order: local and school libraries, informational databases and indexes, and the Internet. Libraries remain your first resource because they have been set up specifically to steer you toward materials appropriate for academic projects. Informational databases and indexes are usually available to you only through libraries and their Web sites, so they are a natural follow-

Search libraries strategically. At the library you’ll find books, journals, newspapers, and other materials, both print and electronic, in a collection expertly overseen by librarians and information specialists, who are, perhaps, the most valuable resources in the building. They are specifically trained to help you find what you need. Get to know them.

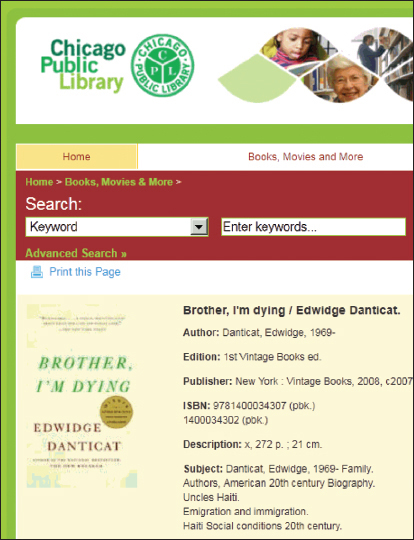

Of course, the key to navigating a library is its catalog. All but the smallest or most specialized libraries now organize their collections electronically (rather than with printed cards), but there’s still a learning curve. The temptation will be to plunge in and start searching. After all, you can locate most items by author, title, subject, keywords, and even call number. But spend a few minutes reading the available Help screens to discover the features and protocols of the catalog. Most searches tell you immediately if the library has a book or journal you need, where it is on the shelves or in data collections, and whether it is available.

Do not ignore, either, the advanced features of a catalog (such as searches by language, by date, by type of content); these options help you find just the items you need or can use. And since you will often use a library not to find specific materials but to choose and develop topics, pay attention to the keywords or search terms the catalog uses to index the subject you’re exploring: You can use index terms for sources you find to look for other similar materials — an important way of generating leads on a subject.

In addition to author, title, and publication information, the full entry for an item in a library catalog will also include subject headings. These terms may suggest additional avenues of research.

Chicago Public Library.

Explore library reference tools. In the age of Wikipedia, it’s easy to forget that libraries still offer truly authoritative source materials in their reference rooms or online reference collections. Such standard works include encyclopedias, almanacs, historical records, maps, archived newspapers, and so on.

Quite often, for instance, you will need reliable biographical facts about important people — dates of birth, countries of origin, schools attended, career paths, and so on. You might find enough data from a Web search or a Wikipedia entry for people currently in the news. But to get accurate and substantial materials on historical figures, consult library tools such as the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (focusing on the United Kingdom) or the Dictionary of American Biography. The British work is available in an up-

If you want information from old newspapers, you may need ingenuity. Libraries don’t store newspapers, so local and a few national papers will be available only in clumsy (though usable) microfilm or microfiche form. Just as discouraging, very few older newspapers are indexed. So, unless you know the approximate date of an event, you may have a tough time finding a particular story in the microfilmed copies of newspapers. Fortunately, both the New York Times and Wall Street Journal are indexed and available in most major libraries. You’ll also find older magazines on microfilm. These may be indexed (up to 1982) in print bibliographies such as the Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature. Ask a librarian for assistance.

When your local library doesn’t have resources you need, ask the people at the checkout or reference desks about interlibrary loan. If cooperating libraries have the books or materials you want, you can borrow them at minimal cost. But plan ahead. The loan process takes time.

Use professional databases. Information databases and indexes — our second category of research materials — are also found at libraries, among their electronic resources. These tools give you access to professional journals, magazines, and newspaper archives, in either summary or full-

Many academic research projects, for instance, begin with a search of multidisciplinary databases such as LexisNexis Academic, Academic OneFile, or Academic Search Premier. These über-

For even more in-

Explore the Internet. As you well know, you can find information simply by exploring the Web from your laptop or tablet, using search engines such as Google and Bing to locate data and generate ideas. The territory may seem familiar because you spend so much time there, but don’t overestimate your ability to find what you need online. Browsing the Web daily to check sports scores and favorite blogs is completely different from using the Web for academic work.

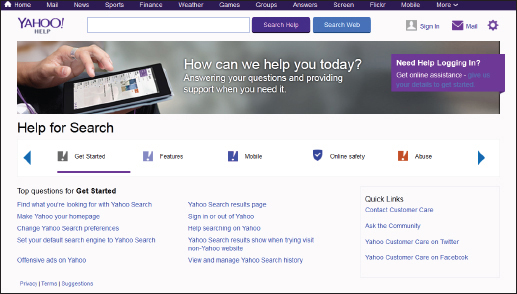

Research suggests that many students begin their projects by simply typing obvious terms into Web browsers, ignoring the advanced capabilities of search engines. To take more control of searches, follow the links on search engine screens that you now probably ignore: Learn to use the tools such as Advanced Search; Search Help; Help; Fix a Problem; Tips & Tricks; Useful Features; and More. You’ll be amazed what you discover.

Then exercise care with Web sources. Always be sure you know who is responsible for the material you are reading (for instance, a government agency, a congressional office, a news service, a corporation), who is posting it, who is the author of the material or sponsor of the Web site, what the date of publication is, and so on. (find reliable sources) A site’s information is often skewed by those who pay its bills or run it; it can also be outdated if no one regularly updates the resource.

Keep current with Web developments too. Web companies such as Google are making more books and journal articles both searchable and available through their sites. Examine these resources as they come online. For instance, a tool such as Google Scholar will direct you to academic studies and scholarly papers on a given topic — exactly the kind of material you want to use in term papers or reports.

As an experiment, you might compare the hits you get on a topic with a regular Google search with those that turn up when you select the Scholar option. You’ll quickly notice that the Scholar items are more serious and technical — and also more difficult to access. In some cases, you may see only an abstract of a journal article or the first page of the item. Yet the materials you locate may be worth a trip to the library to retrieve in their entirety.

The Yahoo! Help screen provides tips on how to search the Internet. Reproduced with permission of Yahoo.

© 2014 Yahoo. YAHOO! and the YAHOO! logo are registered trademarks of Yahoo.

| Resources to Consult When Conducting Research | |||||||

| Source | What It Provides | Usefulness inAcademic Research | Where to Find It | ||||

| Scholarly Books | Fully documented and detailed primary research and analyses by scholars | Highly useful if not too high- |

Library, Google Scholar | ||||

| Scholarly Journals | Carefully documented primary research by scientists and scholars | Highly useful if not too high- |

Library, databases | ||||

| Newspapers | Accounts of current events | Useful as starting point | Library, microfilm, databases (LexisNexis), Internet | ||||

| Magazines | Wide topic range, usually based on secondary research; written for popular audience | Useful if magazine has serious reputation | Libraries, newsstands, databases (EBSCOhost, InfoTrac), Internet | ||||

| Encyclopedias (General or Discipline- |

Brief articles | Useful as starting point | Libraries, Internet | ||||

| Wikipedia | Open- |

Not considered reliable for academic projects | Internet: www.wikipedia.org | ||||

| Special Collections | Materials such as maps, paintings, artifacts, etc. | Highly useful for specialized projects | Libraries, museums; images available via Internet | ||||

| Government, Academic, or Organization Web Sites | Vast data compilations of varying quality, some of it reviewed | Highly useful | Internet sites with URLs ending in .gov, .edu, or .org | ||||

| Commercial Web Sites | Information on many subjects; quality varies | Useful if possible biases are known | Internet sites | ||||

| Blogs | Controlled, often highly partisan discussions of specialized topics | Useful when affiliated with reputable sources such as newspapers | Internet | ||||

| Personal Web Sites | Often idiosyncratic information | Rarely useful; content varies widely | Internet | ||||

For a tutorial on online research, see Tutorials > Digital Writing > Online Research Tools

For a tutorial on online research, see Tutorials > Digital Writing > Online Research Tools