DECIDING TO WRITE A CAUSAL ANALYSIS.

DECIDING TO WRITE A CAUSAL ANALYSIS. From climate change to childhood obesity to high school students’ poor performance on standardized tests, the daily news is full of problems framed by how, why, and what if questions. These are often described as issues of cause and effect, terms we’ll use frequently in this chapter. Take childhood obesity. The public wants to know why we have a generation of overweight kids. Too many cheeseburgers? Not enough dodgeball? People worry, too, about the consequences of the trend. Will overweight children grow into obese adults? Will they develop medical problems?

We’re interested in such questions because they really do matter, and we’re often curious to find answers. But successful analyses of this sort call for more than a passing interest. They demand persistence, precision, and research (for more on choosing a genre, see the Introduction). Even then, you’ll have to deal with a world that seems complicated or contradictory. Not every problem or issue can — or should — be explained simply. (analyze claims and evidence)

Don’t jump to conclusions. Think you know why attitudes toward gay marriage changed so quickly or why people have started to resist Hollywood’s summer blockbusters? Guess again. Nothing’s as simple as it seems and trying to argue causes and effects to other people will quickly teach you humility — even if you don’t jump to hasty conclusions. It’s just plain hard to identify which factors, separately or working together, account for a particular event, activity, or behavior. It is tougher still to predict how what’s happening today might affect the future. So approach causal arguments cautiously and prepare to use qualifiers (sometimes, perhaps, possibly) — lots of them. (develop a statement)

Appreciate your limits. There are rarely easy answers when investigating why things happen the way they do. The space shuttle Columbia burned up on reentry in 2003 because a 1.67-

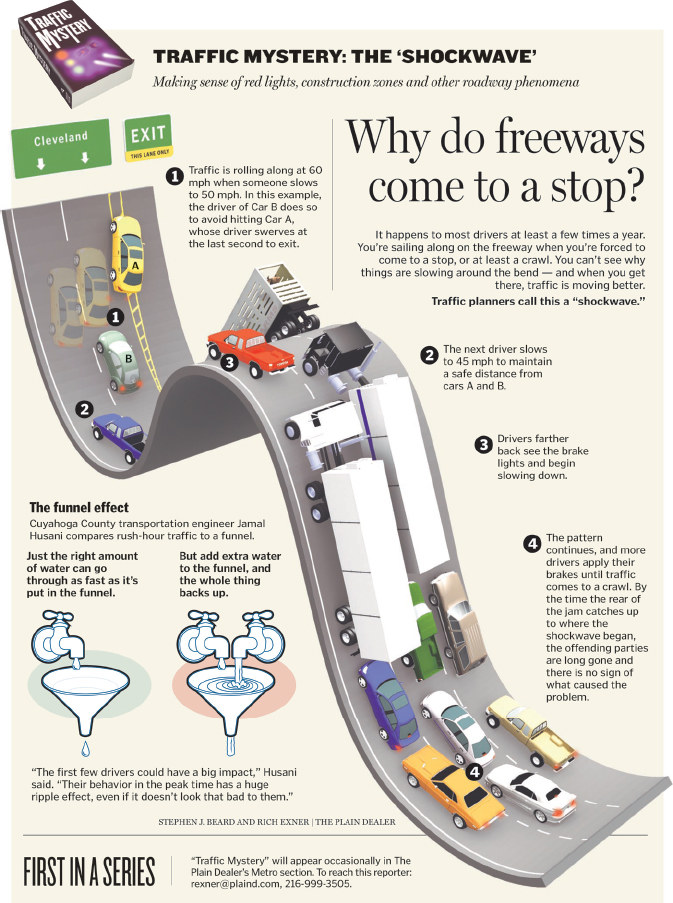

The Funnel Effect We’ve all ground to a halt on freeways without obstacles insight — no weather issues, no collisions, no ducks crossing the pavement. What gives? Highway engineers know.

The Plain Dealer/Landov.

The fact is that you’ll often have to settle for causal explanations that are merely plausible or probable because — outside of the hard sciences — you are often dealing with imprecise and unpredictable forces (especially people).

Offer sufficient evidence for claims. Your academic and professional analyses of cause and effect will be held to high standards of proof — particularly in the sciences. The evidence you provide may be a little looser when you write for popular media, where some readers will tolerate anecdotal and personal examples. But even then, give readers ample reasons to believe you. Avoid hearsay, qualify your claims, and admit when you are merely speculating.