Creating a structure

Creating a structure

organize ideas

The introduction to a cause-

For thousands of years, humans have been training dogs to be hunters, herders, searchers, guards, and companions. Why are we doing so badly? The problem may lie more with our methods than with us.

— Jon Katz, “Train in Vain,” Slate.com, January 14, 2005

In fact, seven paragraphs precede this one to set up the causal claim. Those additional paragraphs help readers (especially dog owners) fully appreciate a problem many will find familiar. The actual first paragraph has author Jon Katz narrating a dog owner’s dilemma.

Sam was distressed. His West Highland terrier, aptly named Lightning, was constantly darting out of doors and dashing into busy suburban Connecticut streets. Sam owned three acres behind his house, and he was afraid to let the dog roam any of it.

By paragraph seven, Katz has offered enough corroborating evidence to describe a crisis in dogdom, a problem that leaves readers hoping for an explanation.

The results of this failure are everywhere: Neurotic and compulsive dog behaviors like barking, biting, chasing cars, and chewing furniture — sometimes severe enough to warrant antidepressants — are growing. Lesser training problems — an inability to sit, stop begging, come, or stay — are epidemic.

Like Katz, you’ll want to take the time necessary to introduce your subject and get readers invested in the issue. Then you have a number of options for developing your explanation or causal analysis.

Explain why something happened. When simply suggesting causes to explain a phenomenon, you can move quickly from an introduction that explains the phenomenon to a thesis or hypothesis. Then work through your list of factors toward a conclusion. Build toward the most convincing explanation.

Introduction leading to an explanatory or causal claim

First cause explored + reasons/evidence

Next cause explored + reasons/evidence . . .

Best cause explored + reasons/evidence

Conclusion

Explain the consequences of a phenomenon. When exploring effects that follow from some cause, event, policy, or change in the status quo, open by describing the situation you believe will have serious consequences. Then work through those effects, connecting them as you need to. Draw out the implications of your analysis in the conclusion.

Introduction describing a significant cause

First effect likely to follow + reasons

Other effect(s) likely to follow + reasons . . .

Conclusion and discussion of implications

Suggest an alternative view of cause and effect. A natural strategy is to open a causal analysis by refuting someone else’s faulty claim and then offering a better one of your own. After all, we often think about causality when someone makes a claim we disagree with.

Introduction questioning a causal claim

Reasons to doubt claim offered + evidence

Alternative cause(s) explored . . .

Best cause examined + reasons/evidence

Conclusion

Explain a chain of causes. Sometimes you’ll describe causes that operate in order, one by one: A causes B, B leads to C, C trips D, and so on. In such cases, use a sequential or narrative pattern of organization, giving special attention to the links (or transitions) within the chain. (shape your work)

Introduction suggesting a chain of causes/consequences

First link presented + reasons/evidence

Next link(s) presented + reasons/evidence . . .

Final link presented + reasons/evidence

Conclusion

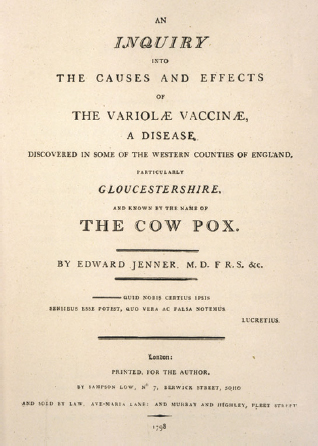

People have been writing causal analysis for centuries. Here is the title page of Edward Jenner’s 1798 publication, An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae. Jenner’s research led to a vaccine that protected human beings from smallpox.

© Mary Evans Picture Library/Everett Collection.