Exploring purpose and topic

Exploring purpose and topic

find a text

In most cases, you write a literary analysis to meet a course requirement, a paper usually designed to improve your skills as a reader of literature and art. Such a lofty goal, however, doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy the project or put your own spin on it.

Your first priority is to read any assignment sheet closely to find out exactly what you are asked to do. Underline any key words in the project description and take them seriously. Typically, you will see terms such as compare and contrast, classify, analyze, or interpret. They mean different things, and each entails a different strategy.

Once you know your goal in writing an analysis, you may have to choose a subject. (get an idea) It’s not unusual to have your instructor assign a work (Three pages on The House on Mango Street by Friday). But just as often, you’ll select a work to study from within a range defined by the title of the course: Mexican American Literature; Major Works of Dostoyevsky; Banned Books. Which should you choose?

Choose a text you connect with. It makes sense to spend time writing about works that move you, perhaps because they touch on an aspect of your life or identity. You may feel more confident studying them because of who you are and what you’ve experienced.

Choose a text you want to learn more about. In the backs of their minds, most people have lists of works and artists they’ve always wanted to explore. So turn an assignment into an opportunity to sample one of them: Beowulf; The Chronicles of Narnia; or the work of William Gibson, Leslie Marmon Silko, or the Clash. Or use an assignment to push beyond the works that are from within your comfort zone, or familiar to your own experience: Examine writers and artists from cultures different from your own and with challenging points of view.

Choose a text you don’t understand. Most students write about accessible works that are relatively new: Why struggle with a hoary epic poem when you can just watch The Lord of the Rings on DVD? One obvious reason may be to figure out how works from unfamiliar times still powerfully connect to our own; the very strangeness of older and more mysterious texts may even rouse you to ask better questions. You’ll pay more attention to literary texts that puzzle you.

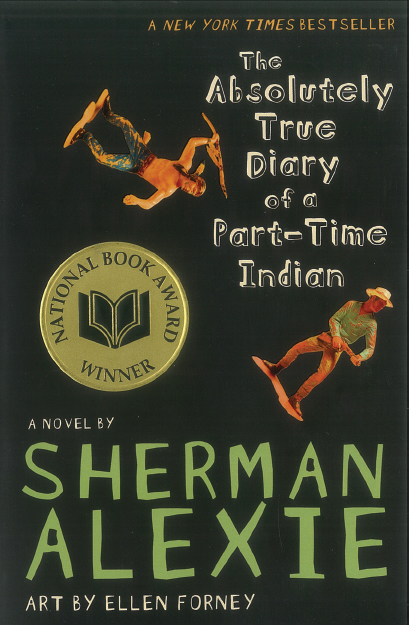

Cover of Sherman Alexie’s Award-

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-