Introduction for Chapter 1

Printed Page 2

Important Events

KINGS IN ANCIENT EGYPT BELIEVED the gods judged them in the afterlife. In Instructions for Merikare, written around 2100–2000 B.C.E., a king advises his son: “Secure your place in the cemetery by being upright, by doing justice, upon which people’s hearts rely. . . . When a man is buried and mourned, his deeds are piled up next to him as treasure.” Being judged pure of heart led to an eternal reward: “abiding [in the afterlife] like a god, roaming [free] like the lords of time.”

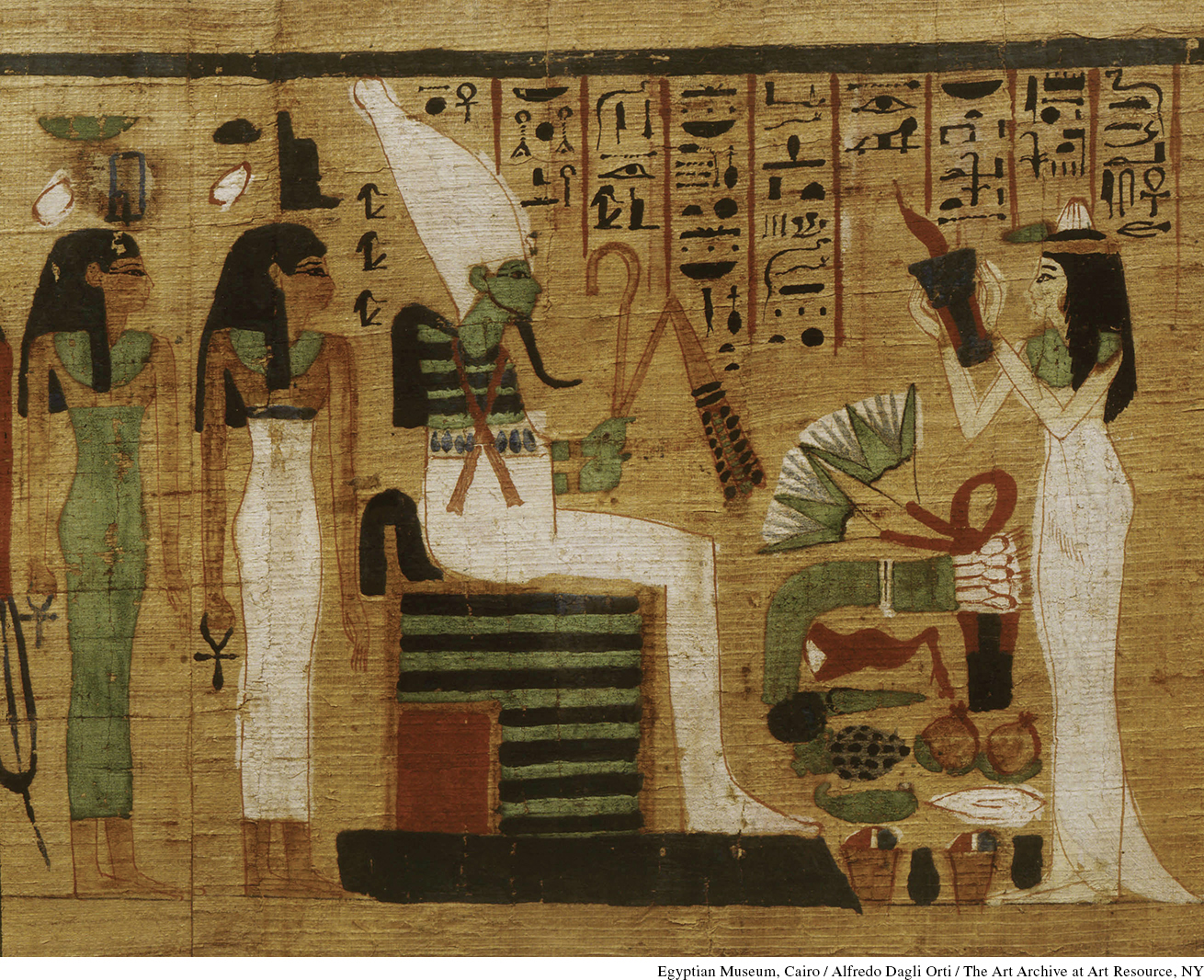

Ordinary Egyptians, too, believed they should live justly by worshipping the gods and obeying the king. A guidebook instructing mummies about the underworld, the Book of the Dead, said the jackal-headed god Anubis would weigh the dead person’s heart against the goddess Maat and her feather of Truth, with the bird-headed god Thoth recording the result. Pictures in the book show the Swallower of the Damned—with a crocodile’s head, a lion’s body, and a hippopotamus’s hind end—crouching ready to eat the heart of anyone who failed. Egyptian mythology thus taught that living a just life was the most important human goal because it won a blessed existence after death.

This belief—that there is a divine world more powerful than the human—goes back to the time before civilization, when people in the Stone Age lived as hunter-gatherers. Ten to twelve thousand years ago, when a global warming led to the invention of agriculture and the domestication of animals, human life changed in revolutionary ways that still affect our lives today. Civilization first emerged around 4000–3000 B.C.E. in cities in Mesopotamia (the region between the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers, today Iraq). Historians define civilization as a way of life based on agriculture and trade, with cities containing large buildings for religion and government; technology to produce metals, textiles, pottery, and other manufactured objects; and knowledge of writing. Current archaeological research indicates that those conditions first existed in Mesopotamia. (See “Terms of History: Civilization.”)

Civilization always arose with religion at its core. In Mesopotamian civilization, rulers believed they were judged for maintaining order on earth and honoring the gods. Egyptian civilization, which began about 3100–3000 B.C.E., built enormous temples and pyramids. Civilizations emerged starting about 2500 B.C.E. in India, China, and the Americas. By 2000 B.C.E., civilizations appeared in Anatolia (today Turkey), on islands in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, and in Greece. The formation of civilization produced intended and unintended consequences. The spread of metallurgy (using high heat to extract metals from ores), for example, created better tools and weapons but also increased preexisting social hierarchy (ranking people as superiors or inferiors).

CHAPTER FOCUS What changes did Western civilization bring to human life?

The peoples of Mesopotamia, Egypt, the eastern Mediterranean, and Greece created Western civilization by exchanging ideas, technologies, and objects through trade, travel, and war. Building on concepts from the Near East, Greeks originated the idea of the West as a separate region, identifying Europe as the West (where the sun sets) and different from the East (where the sun rises). The making of the West depended on cultural, political, and economic interaction among diverse groups. The West remains an evolving concept, not a fixed region with unchanging borders and members.