The Establishment of the Athenian Empire

Printed Page 81

Important EventsThe Establishment of the Athenian Empire

Sparta and Athens built up separate alliances to strengthen their own positions, believing that their security depended on winning a competition for power. Sparta led strong infantry forces from the Peloponnese region, and its ally Corinth had a sizable navy. The Spartan alliance had an assembly to decide policy, but Sparta dominated.

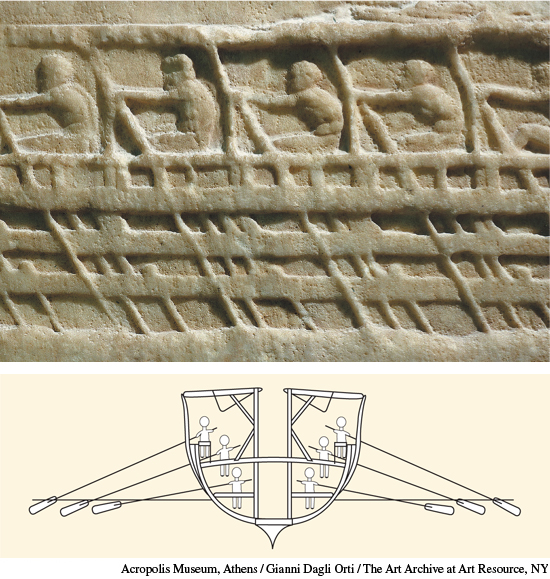

Athens allied with city-states in northern Greece, on the islands of the Aegean Sea, and along the Ionian coast—the places most threatened by Persia. This alliance, the Delian League, was built on naval power. It began as a democratic alliance, but Athens soon controlled it because the allies allowed the Athenians to command and to set the financing arrangements for the league’s fleet. At its height, the league included some three hundred city-states. Each paid dues according to its size; Athens determined how the dues were spent. Larger city-states paid their dues by sending triremes—warships propelled by 170 rowers on three levels and equipped with a battering ram at the bow (Figure 3.1)—complete with trained crews and their pay. Smaller states could share in building one ship or contribute money instead of ships and crews.

Over time, more and more Delian League members voluntarily paid cash because it was easier. Athens then used this money to construct triremes and pay men to row them; oarsmen who brought a slave to row alongside them earned double pay. Drawn primarily from the poorest citizens, rowers gained both income and political influence in Athenian democracy because the navy became the city-state’s main force. These benefits made poor citizens eager to expand Athens’s power over other Greeks. The increase in Athenian naval power thus promoted the development of a wider democracy at home, but it undermined the democracy of the Delian League.

The Athenian assembly could use the league fleet to force disobedient allies to pay cash dues. Athens’s dominance of the Delian League has led historians to use the label Athenian Empire. By about 460 B.C.E., the Delian League’s fleet had expelled all Persian garrisons from northern Greece and driven the enemy fleet from the Aegean Sea. This sweep eliminated the Persian threat for the next fifty years.

Military success made Athens prosperous by bringing in spoils and cash dues from the Delian League and making seaborne trade safe. The prosperity benefited rich and poor alike—the poor rowers earned good pay, while elite commanders enhanced their chances for election to high office by spending their spoils from war on public festivals and buildings. In this way, the democracy of Golden Age Athens supported what modern scholars often label imperialism.