Women, Slaves, and Metics

Printed Page 90

Important EventsWomen, Slaves, and Metics

Women, slaves, and metics (foreigners granted permanent residence status in return for taxes and military service) made up the majority of Athens’s population, but they lacked political rights. Citizen women enjoyed legal privileges and social status, earning respect through their family roles and religious activities. Upper-class women managed their households, visited female friends, and participated in religious cults. Poor women worked as small-scale merchants, crafts producers, and agricultural laborers. Slaves and metics performed a variety of jobs in agriculture and commerce.

Bearing children in marriage earned women public and family status. Men were expected to respect and support their wives. Childbirth was dangerous under the medical conditions of the time. In Medea, a play of 431 B.C.E. by Euripides (c. 480–406 B.C.E.), the heroine shouts in anger at her husband, who has selfishly betrayed her: “People say that we women lead a safe life at home, while men have to go to war. What fools they are! I would much rather fight in battle three times than give birth to a child even once.”

Wives were partners with their husbands in owning and managing the household’s property to help the family thrive. Rich women acquired property, including land—the most valued possession in Greek society because it could be farmed or rented out for income—through inheritance and dowry. A husband often had to put up valuable land of his own as collateral to guarantee repayment to his wife of the amount of her dowry if he squandered it. (See “Contrasting Views: The Nature of Women and Marriage.”)

Like fathers, mothers were expected to hand down property to their children to keep it in the family through male heirs, since only sons could maintain their father’s family line; married daughters became members of their husband’s family. The goal of keeping property in the possession of male heirs shows up most clearly in Athenian law about heiresses (daughters whose fathers died without any sons, which happened in about one of every five families): the closest male relative of the heiress’s father—her official guardian after her father’s death—was required to marry her. The goal was to produce a son to inherit the father’s property. This rule applied regardless of whether either party was already married (unless the heiress had sons); the heiress and the male relative were both supposed to divorce their present spouses and marry each other. In real life, however, people often used legal technicalities to get around this requirement so that they could remain with their chosen partners.

Tradition restricted women’s freedom of movement to protect them, men said, from seducers and rapists. Men wanted to ensure that their family property went only to their biological children. Well-off city women were expected to avoid contact with male strangers. Modern research has discredited the idea that Greek homes had a defined “women’s quarter” to which women were confined. Rather, women were granted privacy in certain rooms. In their homes women would spin wool for clothing, converse with visiting friends, direct their children, supervise the slaves, and present opinions on everything, including politics, to their male relatives. Poor women had to leave the house, usually a crowded rental apartment, to sell bread, vegetables, simple clothing, or trinkets they had made.

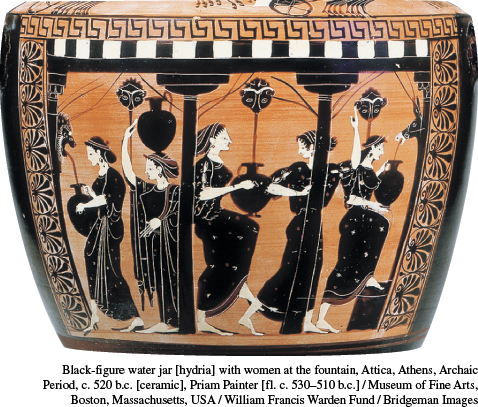

An elite woman left home for religious festivals, funerals, childbirths at the houses of relatives and friends, and shopping. Often her husband escorted her, but sometimes she took only a slave, setting her own itinerary. Most upper-class women probably viewed their limited contact with men as a badge of superior social status. For example, a pale complexion, from staying inside much of the time, was much admired as a sign of an enviable life of leisure and wealth.

Women who bore legitimate children gained increased respect and freedom, as an Athenian man explained in his speech defending himself for having killed his wife’s lover:

After my marriage, I at first didn’t interfere with my wife very much, but neither did I allow her too much independence. I kept an eye on her. . . . But after she had a baby, I started to trust her more and put her in charge of all my things, believing we now had the closest of relationships.

Bearing male children brought a woman special honor because sons meant security. Sons could appear in court to support their parents in lawsuits and protect them in the streets of Athens, which for most of its history had no regular police force. By law, sons were required to support elderly parents.

Some women escaped traditional restrictions by working as a hetaira (“companion”). Hetairas, usually foreigners, were unmarried, physically attractive, witty in speech, and skilled in music and poetry. Men hired them to entertain at a symposium (a drinking party to which wives were not invited). Their skill at clever teasing and joking with men gave hetairas a freedom of speech denied to “proper” women. Hetairas nevertheless lacked the social status and respectability that wives and mothers possessed.

Sometimes hetairas also sold sex for a high price, and they could control their own sexuality by choosing their clients. Athenian men (but not women) could buy sex as they pleased without legal hindrance. Men (but not women) could also have sex freely with female or male slaves, who could not refuse their masters.

The most skilled hetairas earned enough to live in luxury on their own. The most famous hetaira in Athens was Aspasia from Miletus, who became Pericles’ lover and bore him a son. She dazzled men with her brilliant talk and wide knowledge. Pericles fell so deeply in love with her that he wanted to marry her, despite his own law of 451 B.C.E. restricting citizenship to the children of two Athenian parents.

Great riches also freed a woman from tradition. The most outspoken rich Athenian woman was Elpinike. She once publicly criticized Pericles by sarcastically remarking in front of a group of women who were praising him for an attack on a rebellious Delian League ally, “This really is wonderful, Pericles. . . . You have caused the loss of many good citizens, not in battle against Phoenicians or Persians . . . but in suppressing an allied city of fellow Greeks.”

Slaves and metics were considered outsiders. Both individuals and the city-state owned slaves, who could be purchased from traders or bred in the household. Some people picked up unwanted newborns abandoned by their parents (in an accepted practice called infant exposure) and raised them as slaves. Athens’s commercial growth increased the demand for slaves, who in Pericles’ time made up around 100,000 of the city-state’s total of perhaps 250,000 inhabitants. Slaves worked in homes, on farms, and in crafts shops; rowed alongside their owners in the navy; and toiled in Athens’s dangerous silver mines. Unlike those in Sparta, slaves in Athens almost never rebelled, probably because they originated from too many different places to be able to unite.

Golden Age Athens’s wealth and cultural activities attracted many metics from all around the Mediterranean. By the late fifth century B.C.E., metics constituted perhaps 50,000 to 75,000 of the estimated 150,000 free men, women, and children in the city-state. Metics paid for the privilege of living and working in Athens through a special foreigners’ tax and army service, but they did not become citizens.