The Development of Greek Tragedy

Printed Page 99

Important EventsThe Development of Greek Tragedy

Ideas about the problematic relationship between gods and humans inspired Golden Age Athens’s most prominent cultural innovation: tragic drama. Plays called tragedies were presented over three days at the major annual festival of the god Dionysus in a contest for playwrights, reflecting the competitive spirit of Greek life. Tragedies presented shocking stories involving fierce conflict among powerful men and women, usually from myth but occasionally from recent history. The plots involved themes relevant to controversial issues in contemporary Athens. Therefore, these plays stimulated their large audiences to consider the dangers to their democracy from ignorance, arrogance, and violence. Golden Age playwrights explored topics ranging from the roots of good and evil to the nature of individual freedom and responsibility in the family and the political community. As with other ancient texts, most Greek tragedies have not survived: only thirty-three still exist of the hundreds that were produced at Athens.

Public revenues and mandatory contributions by the rich paid for Athenian dramas. The competition in this public art took place at an annual religious festival honoring the god Dionysus, with an official choosing three authors from a pool of applicants. Each of the finalists presented four plays during the festival: three tragedies in a row (a trilogy), followed by a semicomic play featuring satyrs (mythical half-man, half-animal beings) to end the day on a lighter note. Tragedies were written in verses of solemn language, and many were based on stories about the violent possibilities when gods and humans interacted. The plots often ended with a resolution to the trouble—but only after enormous suffering.

The performances of tragedies in Athens, as in many other cities in Greece, took place during the daytime in an outdoor theater. The theater at Athens was built into the southern slope of the acropolis; it held about fourteen thousand spectators overlooking an open, circular area in front of a slightly raised stage. A tragedy had eighteen cast members, all of whom were men: three actors to play the speaking roles (both male and female characters) and fifteen chorus members. Although the chorus leader sometimes engaged in dialogue with the actors, the chorus primarily performed songs and dances in the circular area in front of the stage, called the orchestra.

A successful tragedy offered a vivid spectacle. The chorus wore elaborate costumes and performed intricate dance routines. The actors, who wore masks, used broad gestures and booming voices to reach the upper tier of seats. A powerful voice was crucial to a tragic actor because words represented the heart of the plays, which featured extensive dialogue and long speeches. Special effects were popular. Actors playing the roles of gods swung from a crane to fly suddenly onto the stage. Actors playing lead roles, called the protagonists (“first competitors”), competed to win the “Best Actor” award. A skilled protagonist was so important to a play’s success that actors were assigned by lottery to the competing playwrights so that all three had an equal chance to have a winning cast. Great protagonists became enormously popular.

Playwrights came from the social elite because only men with wealth could afford the amount of time and learning this work demanded. They served as authors, directors, producers, musical composers, choreographers, and occasionally actors for their own plays. In their lives as citizens, playwrights fulfilled the military and political obligations of Athenian men. The best-known Athenian tragedians—Aeschylus (525–456 B.C.E.), Sophocles (c. 496–406 B.C.E.), and Euripides (c. 485–406 B.C.E.)—all served in the army, and Sophocles was elected to Athens’s highest board of officials. Authors of plays competed from a love of honor, not money. The prizes, determined by a board of judges, awarded high prestige but little cash. The competition was regarded as so important that any judge who took a bribe in awarding prizes was put to death.

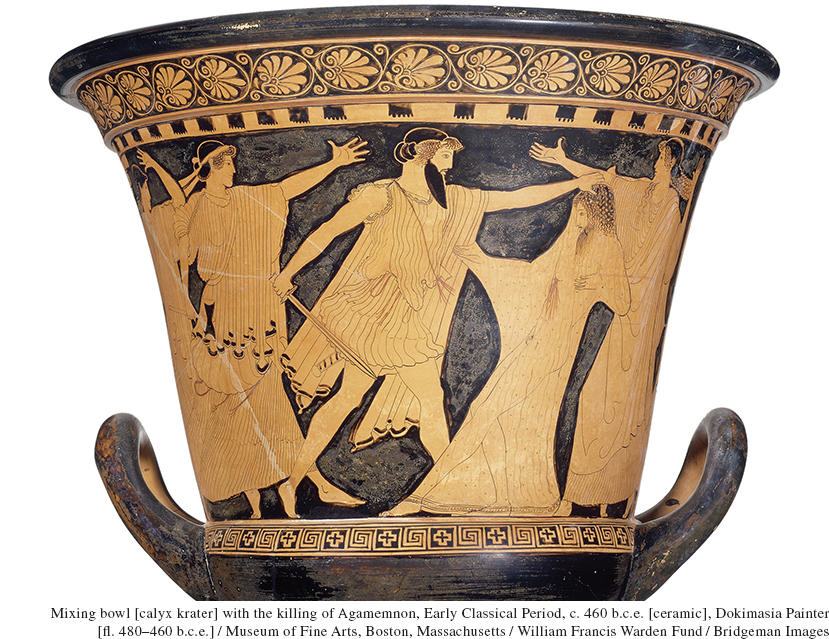

Tragedy’s plots set out the difficulties of telling right from wrong when humans came into conflict and the gods became involved. Even though most tragedies were based on stories that referred to a legendary time before city-states existed, such as the period of the Trojan War, the plays’ moral issues were relevant to the society and obligations of citizens in a city-state. The plays suggest that human beings learn only by suffering but that the gods provide justice in the long run. For example, Aeschylus’s trilogy Oresteia (458 B.C.E.) explains the divine origins of democratic Athens’s court system through the story of the gods finally stopping the murderous violence in the family of Orestes, son of King Agamemnon, the Greek leader against Troy.

Sophocles’ Antigone (441 B.C.E.) presents the story of the cursed family of Oedipus of Thebes as a drama of harsh conflict between a courageous woman, Antigone, and the city-state’s stern male leader, her uncle Creon. After her brother dies in a failed rebellion, Antigone insists on her family’s moral obligation to bury its dead in obedience to divine command. Creon, however, takes harsh action to preserve order and protect community values by prohibiting the burial of his traitorous nephew. In a horrifying story of raging anger and suicide that features one of the most famous heroines of Western literature, Sophocles exposes the right and wrong on each side of the conflict. His play offers no easy resolution of the competing interests of divinely sanctioned moral tradition and the state’s political rules.

Ancient sources report that audiences reacted strongly to the messages of these tragedies. For one thing, spectators realized that the plays’ central characters were figures who fell into disaster even though they held positions of power and prestige. The characters’ reversals of fortune came about not because they were absolute villains but because, as humans, they were susceptible to a lethal mixture of error, ignorance, and hubris (violent arrogance that transformed one’s competitive spirit into a self-destructive force). The Athenian Empire was at its height when audiences at Athens attended the tragedies written by competing playwrights. Thoughtful playgoers could reflect on the possibility that Athens’s current power and prestige, managed as they were by humans, might fall victim to the same kinds of mistakes and conflicts that brought down the heroes and heroines of tragedy. Thus, these publicly funded plays both entertained through their spectacle and educated through their stories and words. In particular, they reminded male citizens—who governed the city-state in its assembly, council, and courts—that success created complex moral problems that self-righteous arrogance turned into community-wide catastrophes.