Life in the Roman Golden Age, 96–180 C.E.

Printed Page 188

Important EventsLife in the Roman Golden Age, 96–180 C.E.

Peace and prosperity in Rome’s Golden Age depended on defense by a loyal military, service by provincial elites in local administration and tax collection, common laws enforced throughout the empire, and a healthy population reproducing itself. The empire’s vast size and the relatively small numbers of soldiers and imperial officials in the provinces meant that emperors had only limited control over these factors.

In theory, Rome’s military goal was to expand perpetually because conquest brought land, money, and glory. In reality, the emperors lacked the resources to expand the empire much beyond the territory that Augustus had controlled, and they had to concentrate on defending imperial territory.

Most provinces were peaceful, housing few troops. Most legions (units of five thousand troops) were stationed on frontiers to prevent invasions from Germanic tribes to the north and Persians to the east. The peace allowed long-distance trade to import luxury goods, such as spices and silk, from as far away as India and China. Roman merchants regularly sailed from Egypt to India and back.

The army of both Romans and noncitizens reflected the population’s diversity. Serving under Roman officers, the non-Romans learned to speak Latin and follow Roman customs. Upon discharge, they received Roman citizenship. Thus the army helped spread a common way of life.

Paying for defense became an impossible problem. Previously, foreign wars had brought in revenue from riches and prisoners of war sold as slaves. Conquered territory also provided regular income from taxes. Now the army was no longer making conquests, but the soldiers had to be paid well to maintain discipline. This made a soldier’s career desirable but cost the emperors dearly.

A tax on agriculture in the provinces (Italy was exempt) now provided the principal source of revenue. The bureaucracy was inexpensive because it was small: only several hundred officials governed a population of about fifty million. Most locally collected taxes stayed in the provinces to pay expenses there, especially soldiers’ pay. Governors with small staffs ran the provinces, which eventually numbered about forty.

The government’s finances depended on tax collection carried out by provincial elites. Serving as decurions (members of municipal Senates), these wealthy men were required personally to guarantee that their area’s financial responsibilities were met. If there was a shortfall in tax collection or local finances, the decurions had to pay the difference from their own pockets. Wise emperors kept taxes moderate. As Tiberius put it when refusing a request for tax increases from provincial governors, “I want you to shear my sheep, not skin them alive.” The financial liability in holding civic office made that honor expensive, but the accompanying prestige made the elite willing to take the risk. Rewards for decurions included priesthoods in the imperial cult, an honor open to both men and women.

The system worked because it observed tradition: the local elites were their communities’ patrons and the emperor’s clients. As long as there were enough rich, public-spirited provincials participating, the principate functioned by fostering the old ideal of community service by the upper class in return for respect and social status.

The provinces contained diverse peoples who spoke different languages, observed different customs, dressed in different styles, and worshipped different divinities (Map 6.2). In the countryside, Roman conquest only lightly affected local customs. In new towns that sprang up around Roman forts or settlements of army veterans, Roman influence predominated. Roman culture had the greatest effect on western Europe, permanently rooting Latin (and the languages that would emerge from it) as well as Roman law and customs there. Eventually, emperors came from citizen-families in the provinces; Trajan, from Spain, was the first.

Romanization, the spread of Roman law and culture in the provinces, raised the standard of living by providing roads and bridges, increasing trade, and establishing peaceful conditions for agriculture. The army’s need for supplies created business for farmers and merchants. The prosperity that provincials enjoyed under Roman rule made Romanization acceptable. In addition, Romanization was not a one-way street. In western regions as diverse as Gaul, Britain, and North Africa, interaction between the local people and Romans produced mixed cultural traditions, especially in religion and art. Therefore, Romanization merged Roman and local culture.

The eastern provinces, however, largely retained their Greek and Near Eastern characteristics. Huge Hellenistic cities such as Alexandria (in Egypt) and Antioch (in Syria) rivaled Rome in size and splendor. The eastern provincial elites readily accepted Roman governance because Hellenistic royal traditions had prepared them to see the emperor as their patron and themselves as his clients.

The continuing vitality of Greek language and culture contributed to new trends in Roman literature. Lucian (c. 117–180 C.E.) composed satirical dialogues in Greek mocking stuffy and superstitious people. The essayist and philosopher Plutarch (c. 50–120 C.E.) also used Greek to write paired biographies of Greek and Roman men. His exciting stories made him favorite reading for centuries; William Shakespeare based several plays on Plutarch’s biographies.

The late first century and early to mid-second century C.E. can be called the Silver Age of Latin literature. Tacitus (c. 56–120 C.E.) wrote historical works that exposed the Julio-Claudian emperors’ ruthlessness. Juvenal (c. 65–130 C.E.) wrote poems ridiculing pretentious Romans while complaining about living broke in the capital. Apuleius (c. 125–170 C.E.) excited readers with a sexually explicit novel called The Golden Ass, about a man turned into a donkey who regains his body and his soul through the kindness of the Egyptian goddess Isis.

The emperors made the laws for the entire empire based on the principle of equity. This meant doing what was “good and fair” even if that required ignoring the letter of the law. This principle taught that a contract’s intent outweighed its words, and that accusers should prove the accused guilty because it was unfair to make defendants prove their innocence. In dealing with accusations against Christians, the emperor Trajan ruled that no one should be convicted on the grounds of suspicion alone because it was better for a guilty person to go unpunished than for an innocent person to be condemned.

The importance of hierarchy led Romans to continue formal distinctions in society based on wealth. The elites constituted a tiny portion of the population. Only about one in every fifty thousand had enough money to qualify for the senatorial order, the highest-ranking class, while about one in a thousand belonged to the equestrian order, the second-ranking class. Different purple stripes on clothing identified these orders. The third-highest order consisted of decurions, the local Senate members in provincial towns.

The legal distinction between the elite and the rest of the population now became stricter. “Better people” included senators, equites, decurions, and retired army veterans. Everybody else—except slaves, who counted as property—made up the vastly larger group of “humbler people.” The law imposed harsher penalties on them than on “better people” for the same crime. “Humbler people” convicted of serious crimes were regularly executed by being crucified or torn apart by wild animals before a crowd of spectators. “Better people” rarely received the death penalty, and those who did were allowed a quicker and more dignified execution by the sword. “Humbler people” could also be tortured in criminal investigations, even if they were citizens. Romans regarded these differences as fair on the grounds that an elite person’s higher status required of him or her a higher level of responsibility for the common good. As one provincial governor expressed it, “Nothing is less equitable than mere equality itself.”

Nothing mattered more to the empire’s strength than steady population levels. Concerns about marriage and reproduction thus filled Roman society; remaining single and childless represented social failure for both women and men. The propertied classes usually arranged marriages. Girls often married in their early teens, to have as many years as possible to bear children. Because so many babies died young, families had to produce numerous offspring to keep from disappearing. The tombstone of Veturia, a soldier’s wife, tells a typical story: “Here I lie, having lived for twenty-seven years. I was married to the same man for sixteen years and bore six children, five of whom died before I did.”

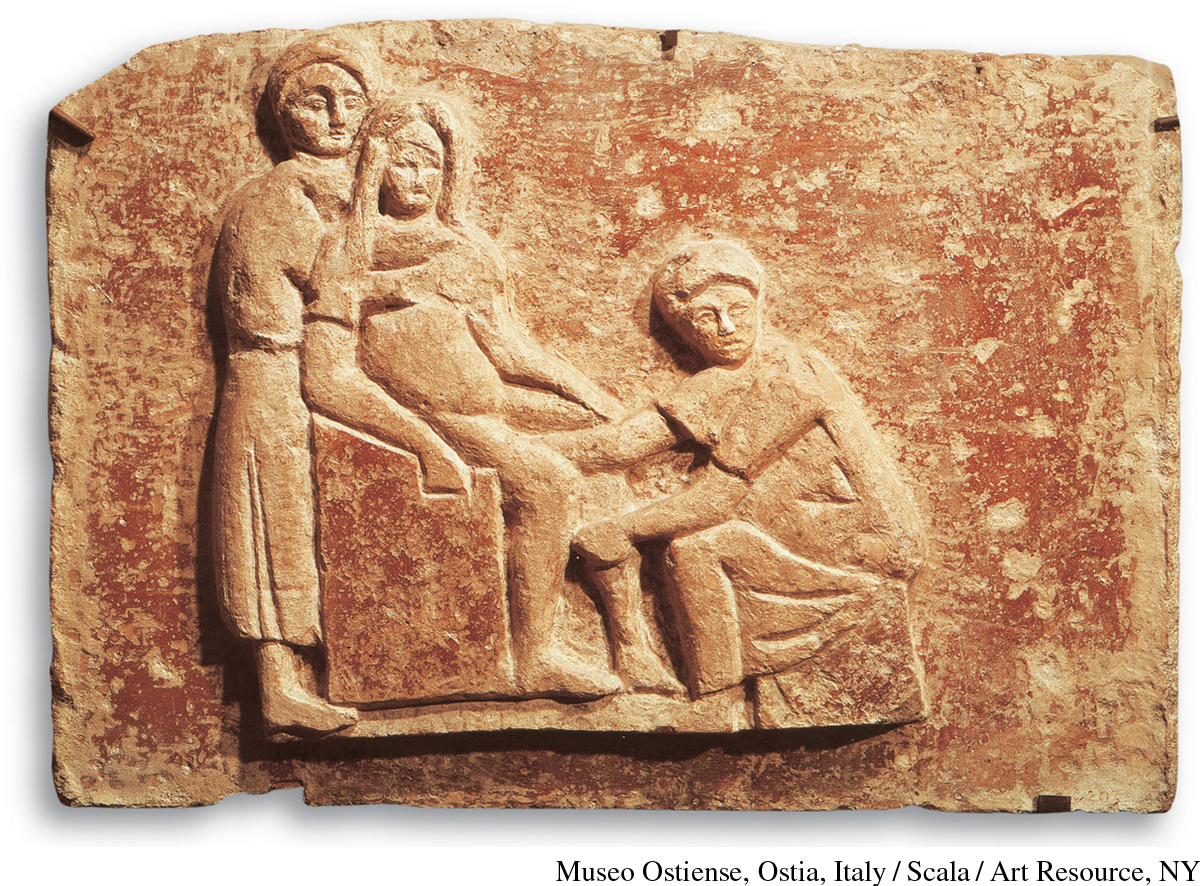

The social pressure to bear numerous children created many health hazards for women. Doctors possessed metal instruments for surgery and physical examinations, but many were poorly educated former slaves with only informal training. There was no official licensing of medical personnel. Complications in childbirth could easily kill the mother because doctors and midwives could not stop internal bleeding or cure infections. Romans controlled reproduction with contraception (by obstructing the vagina or by administering drugs to the female partner) or by abandoning unwanted infants.

REVIEW QUESTION In the early Roman Empire, what was life like in the cities and in the country for the elite and for ordinary people?

The emperors tried to support reproduction. They gave money to feed needy children, hoping they would grow up to have families. Wealthy people often adopted children in their communities. One North African man supported three hundred boys and three hundred girls each year until they grew up.