Growth of a New Religion

Printed Page 196

Important EventsGrowth of a New Religion

Christianity faced serious obstacles as a new religion. Imperial officials, suspecting Christians of being traitors, could prosecute them for refusing to perform traditional sacrifices. Christian leaders had to build an organization from the ground up to administer their growing congregations. Finally, Christians had to decide whether women could continue as leaders in their congregations.

The Roman emperors found Christians baffling and troublesome. Unlike Jews, Christians professed a new faith rather than their ancestors’ traditional religion. Roman law therefore granted them no special treatment, as it did Jews out of respect for the great age of Judaism. Most Romans feared that Christians’ denial of the old gods and the imperial cult would bring divine punishment upon the empire. Secret rituals in which Christians symbolically ate the body and drank the blood of Jesus during communal dinners, called Love Feasts, led to accusations of cannibalism and sexual promiscuity.

Romans were quick to blame Christians for disasters. Nero declared that Christian arsonists set Rome’s great fire, and he covered Christians in animal skins to be torn to pieces by dogs or fastened to crosses and set on fire at night. Nero’s cruelty, however, earned Christians sympathy from Rome’s population.

Persecutions like Nero’s were infrequent. There was no law specifically prohibiting Christianity, but officials could punish Christians, as they could anyone, to protect public order. Pliny’s actions as a provincial governor in Asia Minor illustrated the situation. In about 112 C.E., Pliny asked a group of people accused of following this new religion if they were really Christians. When some said yes, he asked them to reconsider. He freed those who denied Christianity, so long as they sacrificed to the gods, swore loyalty to the imperial cult, and cursed Christ. He executed those who refused these actions. Christians argued that Romans had nothing to fear from their faith. Christianity, they insisted, taught morality and respect for authority. It was the true philosophy, combining the best features of Judaism and Greek thought. (See “Contrasting Views: Christians in the Empire: Conspirators or Faithful Subjects?”)

The occasional persecutions in the early empire did not stop Christianity. Christians like Vibia Perpetua regarded public executions as an opportunity to become a martyr (Greek for “witness”), someone who dies for his or her religious faith. Martyrs’ belief that their deaths would send them directly to paradise allowed them to face torture. Some Christians actively sought to become martyrs. Tertullian (c. 160–240 C.E.) proclaimed that “martyrs’ blood is the seed of the Church.” Ignatius (c. 35–107 C.E.), bishop of Antioch, begged Rome’s congregation, which was becoming the most prominent Christian group, not to ask the emperor to show him mercy after his arrest: “Let me be food for the wild animals [in the arena] through which I can reach God,” he pleaded. “I am God’s wheat, to be ground up by the teeth of beasts so that I may be found pure bread of Christ.” Stories reporting the martyrs’ courage showed that the new religion gave its believers spiritual power to endure suffering.

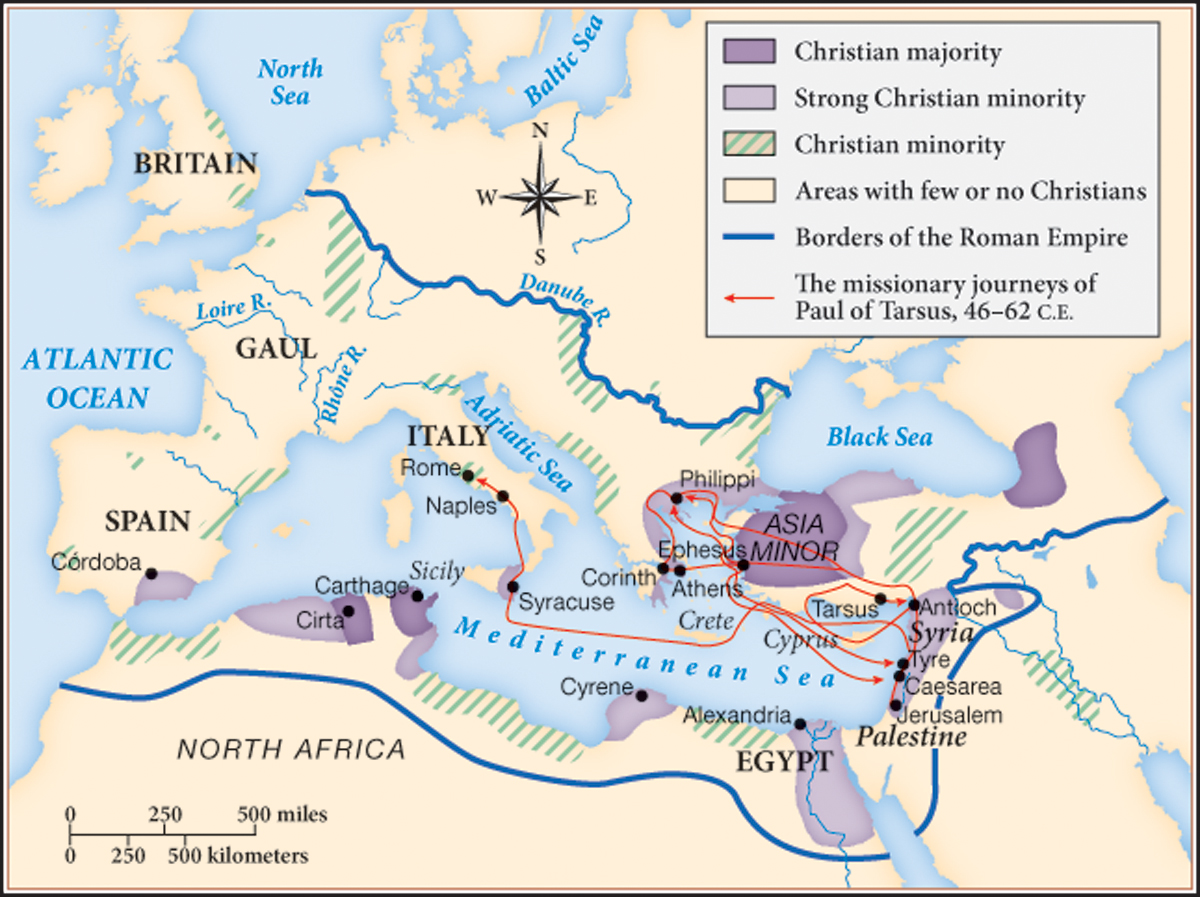

First-century C.E. Christians expected Jesus to return to pass judgment on the world during their lifetimes. When that did not happen, they began transforming their religion from an apocalyptic Jewish sect expecting the immediate end of the world into one that could survive indefinitely. This transformation was painful because early Christians fiercely disagreed about what they should believe, how they should live, and who had the authority to decide these questions. Some insisted Christians should withdraw from the everyday world to escape its evil, abandoning their families and shunning sex and reproduction. Others believed they could follow Christ’s teachings while living ordinary lives. Many Christians worried they could not serve as soldiers without betraying their faith because the army participated in the imperial cult. This dilemma raised the further issue of whether Christians could remain loyal subjects of the emperor. Disagreement over these doctrinal questions raged in the many congregations that arose in the early empire around the Mediterranean, from Gaul to Africa to the Near East (Map 6.3).

The need to deal with such tensions, to administer the congregations, and to promote spiritual communion among believers led Christians to create an official hierarchy of men, headed by bishops. They spearheaded the drive to build the connection between congregations and Christ that promised salvation to believers. Bishops possessed authority to define Christian doctrine and administer practical affairs for congregations. The emergence of bishops became the most important institutional development in early Christianity. Bishops received their positions according to the principle later called apostolic succession, which states that the Apostles appointed the first bishops as their successors, granting these new officials the authority Jesus had originally given to the Apostles. Those designated by the Apostles in turn appointed their own successors. Bishops had authority to ordain ministers with the holy power to administer the sacraments, above all baptism and communion, which believers regarded as necessary for achieving eternal life. Bishops also controlled their congregations’ memberships and finances. The money financing the early church came from members’ donations.

The bishops tried to suppress the disagreements that arose in the new religion. They used their authority to define orthodoxy (true doctrine) and heresy (false doctrine). The meetings of the bishops of different cities constituted the church’s organization in this period. Today this loose organization is referred to as the early Catholic (Greek for “universal”) church. Since the bishops often disagreed about doctrine and about which bishops should have greater authority than others, unity remained impossible to achieve.

When the male bishops came to power, they demoted women from positions of leadership. This change reflected their view that in Christianity women should be subordinate to men, just as in Roman imperial society in general. Some congregations took a long time to accept this shift, however, and women still claimed authority in some groups in the second and third centuries C.E. In late-second-century C.E. Asia Minor, for example, Prisca and Maximilla declared themselves prophetesses with the power to baptize believers in anticipation of the coming end of the world. They spread the apocalyptic message that the heavenly Jerusalem would soon descend in their region.

Excluded from leadership posts, many women chose a life without sex to demonstrate their devotion to Christ. Their commitment to celibacy gave these women the power to control their own bodies. Other Christians regarded women who reached this special closeness to God as holy and socially superior. By rejecting the traditional roles of wife and mother in favor of spiritual excellence, celibate Christian women achieved independence and status otherwise denied them.