Competing Religious Beliefs

Printed Page 199

Important EventsCompeting Religious Beliefs

Three centuries after Jesus’s death, traditional polytheism was still the religion of the overwhelming majority of the Roman Empire’s population. Polytheists, who worshipped a variety of gods in different ways in diverse kinds of sanctuaries, often reflecting regional religious rituals and traditions, never created a unified religion. Nevertheless, the stability and prosperity of the early empire gave traditional believers confidence that the old gods and the imperial cult protected them. Even those who preferred religious philosophy, such as Stoicism’s idea of divine providence, respected the old cults because they embodied Roman tradition. By the third century C.E., the growth of Christianity, along with the persistence of Judaism and polytheistic cults, meant that people could choose from a number of competing beliefs. Especially appealing were beliefs that offered people hope that they could change their present lives for the better and also look forward to an afterlife.

Polytheistic religion aimed at winning the goodwill of all the divinities who could affect human life. Its deities ranged from the state cults’ major gods, such as Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, to spirits thought to inhabit groves and springs. International cults such as the mystery cults of Demeter and Persephone outside Athens remained popular.

The cults of Isis and Mithras demonstrate how polytheism could provide a religious experience arousing strong emotions and demanding a moral way of life. The Egyptian goddess Isis had already attracted Romans by the time of Augustus, who tried to suppress her cult because it was Cleopatra’s religion. But the fame of Isis as a kind, compassionate goddess who cared for her followers made her cult too popular to crush: the Egyptians said it was her tears for starving humans that caused the Nile to flood every year and bring them good harvests. Her image was that of a loving mother, and in art she was often depicted nursing her son. Her cult’s central doctrine concerned the death and resurrection of her husband, Osiris. Isis also promised her believers a life after death.

Isis required her followers to behave righteously. Many inscriptions expressed her high moral standards by listing her own civilizing accomplishments: “I broke down the rule of tyrants; I put an end to murders; I caused what is right to be mightier than gold and silver.” The hero of Apuleius’s novel The Golden Ass shouts out his intense joy after his rescue and spiritual rebirth through Isis: “O holy and eternal guardian of the human race, who always cherishes mortals and blesses them, you care for the troubles of miserable humans with a sweet mother’s love. Neither day nor night, nor any moment of time, ever passes by without your blessings.” Other cults also required worshippers to lead upright lives. Inscriptions from Asia Minor, for example, record people’s confessions to sins such as sexual transgressions for which their local god had imposed severe penance.

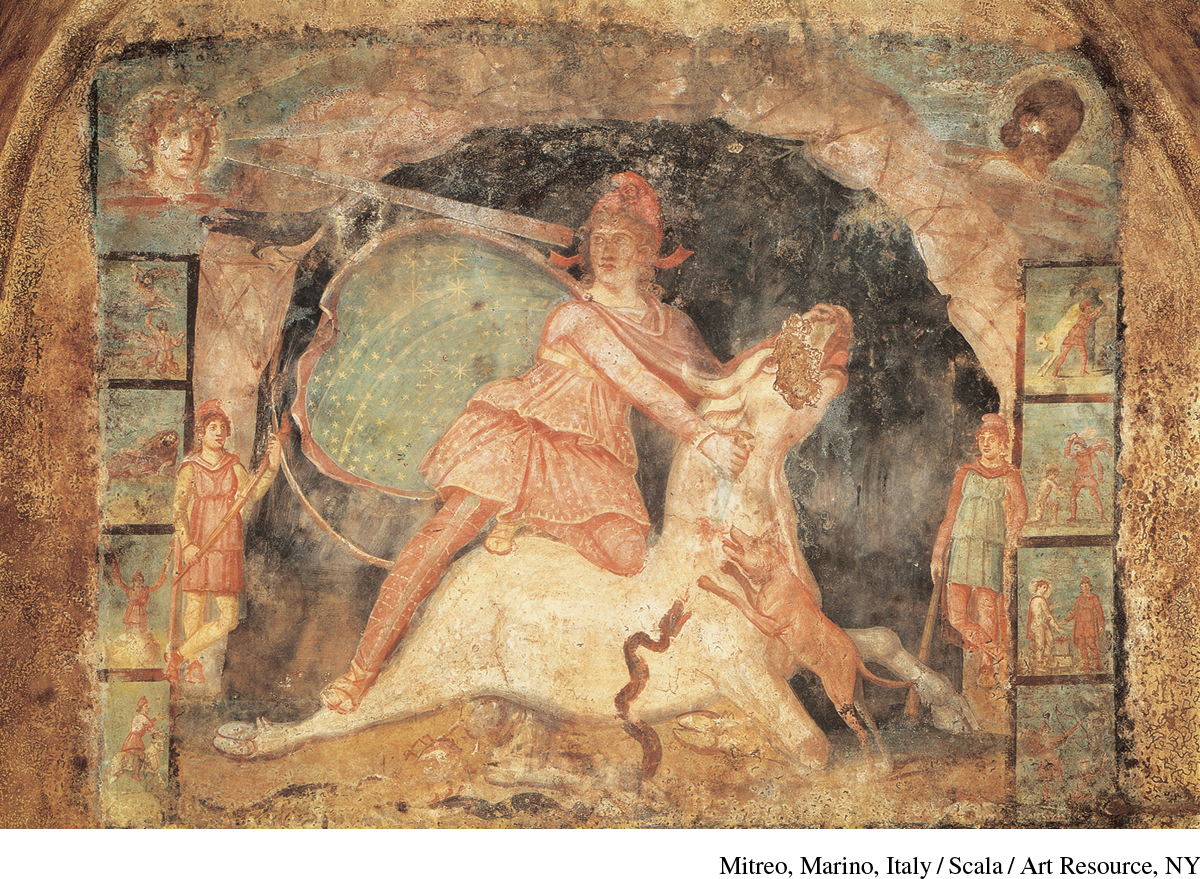

Archaeology reveals that the cult of Mithras had many shrines under the Roman Empire, but no texts survive to explain its mysterious rituals and symbols, which Romans believed had originated in Persia. Mithras’s legend said that he killed a bull in a cave, apparently as a sacrifice for the benefit of his worshippers. As pictures show, this was an unusual sacrifice because the animal was allowed to struggle as it was killed. Initiates in Mithras’s cult proceeded through rankings named, from bottom to top, Raven, Male Bride, Soldier, Lion, Persian, Sun-runner, and Father—the latter a title of great honor.

Many upper-class Romans also guided their lives by Greek philosophy. Most popular was Stoicism, which presented philosophy as the “science of living” and required self-discipline and duty from men and women alike. (See “Philosophy for a New Age” in Chapter 4 and “Document 6.3: A Roman Stoic Philosopher on the Capabilities of Women”.) Philosophic individuals put together their own set of beliefs, such as those on duty expressed by the emperor Marcus Aurelius in his memoirs expressing Stoic ideas, entitled To Myself (or Meditations). In this moving personal journal, the most powerful man in the Roman world told himself that “when it’s hard to get out of bed in the morning, keep it in mind that you are getting up to do the work of a human being.”

REVIEW QUESTION Which aspects of social, cultural, and political life in the early Roman Empire supported the growth of Christianity, and which opposed it?

Christian and polytheist intellectuals debated Christianity’s relationship to Greek philosophy. Origen (c. 185–255 C.E.) argued that Christianity was superior to Greek philosophical doctrines as a guide to correct living. At about the same time, Plotinus (c. 205–270 C.E.) developed the philosophy that had the greatest influence on religion. His spiritual philosophy was influenced by Persian religious ideas and, above all, Plato’s philosophy, for which reason it is called Neoplatonism. Plotinus’s ideas deeply influenced many Christian thinkers as well as polytheists. He wrote that ultimate reality is a trinity of The One, of Mind, and of Soul. By rejecting the life of the body and relying on reason, individual souls could achieve a mystic union with The One, who in Christian thought would be God. To succeed in this spiritual quest required strenuous self-discipline in personal morality and spiritual purity as well as in philosophical contemplation.