Uncontrolled Spending, Natural Disasters, and Political Crisis, 193–284 C.E.

Printed Page 203

Important EventsUncontrolled Spending, Natural Disasters, and Political Crisis, 193–284 C.E.

The emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211 C.E.) and his son and successor Caracalla (r. 211–217 C.E.) made financial crisis unavoidable when they drained the treasury to satisfy the army and their own dreams of glory. A soldier’s soldier from North Africa, Severus became emperor when his predecessor’s incompetence caused a government crisis and civil war. Seeking to restore imperial prestige and acquire money from foreign conquest, Severus campaigned beyond the frontiers of the provinces in Mesopotamia and Scotland.

Since extreme inflation had reduced their wages to almost nothing, soldiers expected the emperors to provide gifts of extra money. Severus spent large sums on gifts and raised soldiers’ pay by a third. The army’s expanded size made this raise more expensive than the treasury could handle. The out-of-control spending did not trouble Severus. His deathbed advice to his sons, Caracalla and Geta, in 211 C.E. was to “stay on good terms with each other, be generous to the soldiers, and pay no attention to anyone else.”

Ignoring the first part of his father’s advice, Caracalla murdered his brother. He then went on to end the Roman Golden Age of peace and prosperity with his uncontrolled spending and cruelty. He increased the soldiers’ pay by another 40 to 50 percent and spent gigantic sums on building projects, including the largest public baths Rome had ever seen, covering blocks and blocks of the city. These huge expenses put unbearable pressure on the local provincial officials responsible for collecting taxes and on the citizens, whom the officials in turn squeezed for ever larger payments.

In 212 C.E., Caracalla tried to fix the budget by granting Roman citizenship to almost every man and woman in imperial territory except slaves. Since only citizens paid inheritance taxes and fees for freeing slaves, an increase in citizens meant an increase in revenues, most of which was earmarked for the army. But too much was never enough for Caracalla, whose cruelty to anyone who displeased him made his contemporaries whisper that he was insane. His attempted conquests of new territory failed to bring in enough funds, and he wrecked imperial finances. Once when his mother reprimanded him for his excesses he replied, as he drew his sword, “Never mind, we won’t run out of money as long as I have this.”

The financial crisis generated political instability that led to a half century of civil war. This period of violent struggle destroyed the principate. More than two dozen men, often several at once, held or claimed power in this period. Their only qualification was their ability to command a frontier army and to reward the troops for loyalty to their general instead of to the state.

The civil war devastated the population and the economy. Violence and hyperinflation made life miserable in many regions. Agriculture withered as farmers could not keep up normal production when armies searching for food ravaged their crops. City council members faced constantly escalating demands for tax revenues from the swiftly changing emperors. The endless financial pressure destroyed members’ will to serve their communities.

Earthquakes and epidemics also struck the provinces in the mid-third century. In some regions, the population declined significantly as food supplies became less dependable, civil war killed soldiers and civilians alike, and infection raged. The loss of population meant fewer soldiers for the army, whose strength as a defense and police force had been gutted by political and financial chaos. This weakness made frontier areas more vulnerable to raids and allowed roving bands of robbers to range unchecked inside the borders.

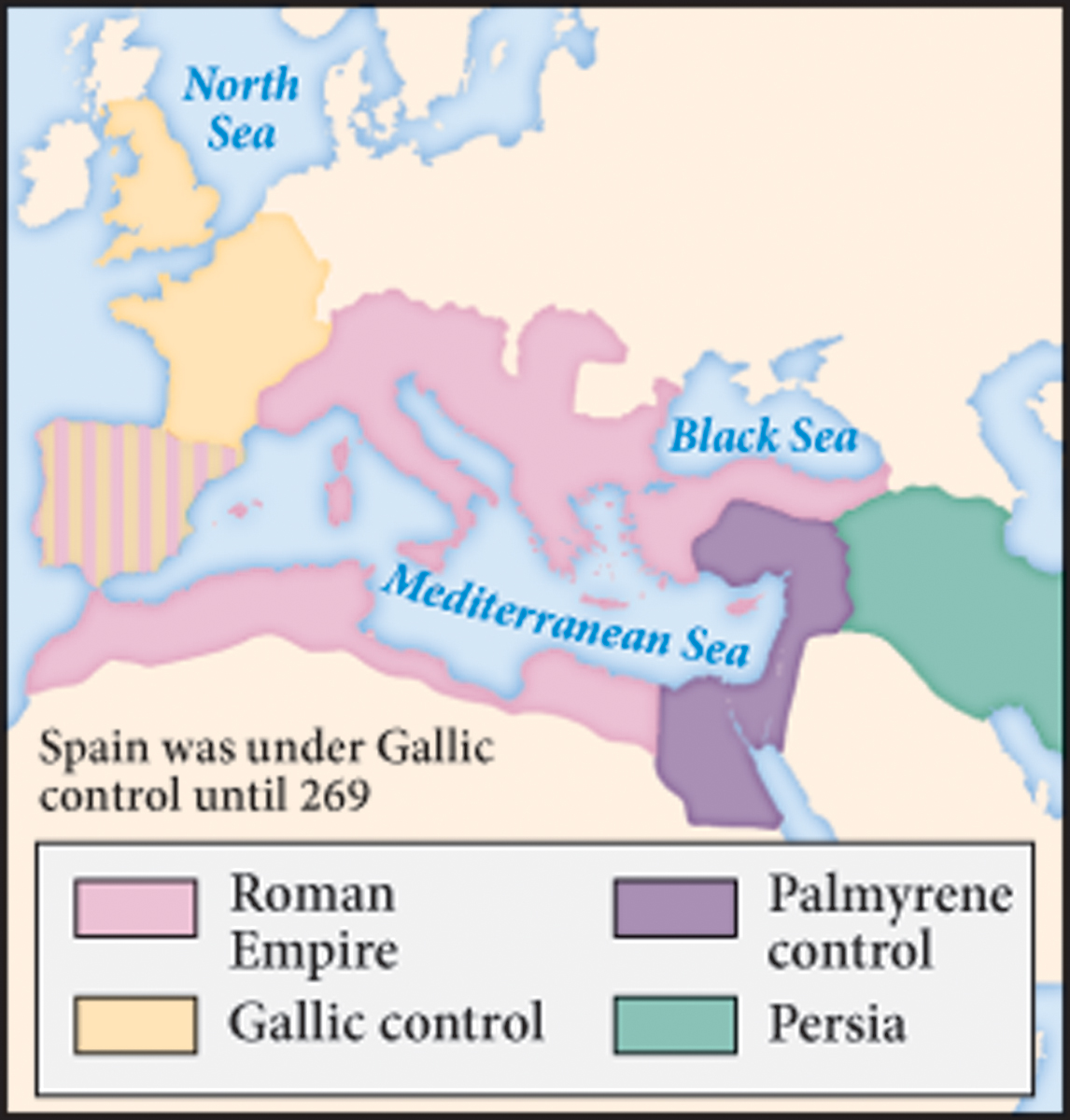

Foreign enemies to the north and east took advantage of the third-century crisis to attack. Roman fortunes hit bottom when Shapur I, king of the Sasanid Empire of Persia, invaded the province of Syria and captured the emperor Valerian (r. 253–260 C.E.). By this time, Roman imperial territory was in constant danger of being captured. Zenobia, the warrior queen of Palmyra in Syria, for example, seized Egypt and Asia Minor. Emperor Aurelian (r. 270–275 C.E.) won back these provinces only with great difficulty. He also had to encircle Rome with a larger wall to ward off attacks from northern raiders, who were smashing their way into Italy.

REVIEW QUESTION What were the causes and the effects of the Roman crisis in the third century C.E.?

Polytheists explained the third-century crisis in the traditional way: the state gods were angry about something. But what? To them, the obvious answer was the presence of Christians, who denied the existence of the Roman gods and refused to worship them. Emperor Decius (r. 249–251 C.E.) therefore launched a systematic persecution to eliminate Christians and restore the goodwill of the gods. He ordered all the empire’s inhabitants to prove their loyalty to the state by sacrificing to its gods. Christians who refused were killed. This persecution did not stop the civil war, economic failure, and natural disasters that threatened Rome’s empire, and Emperor Gallienus (r. 253–268 C.E.) ordered Christians to be left alone and their property restored. The crisis in government continued, however, and by the 280s C.E. the principate had reached a political and financial dead end.