The Creation of the Principate, 27 B.C.E.–14 C.E.

Printed Page 177

Important EventsThe Creation of the Principate, 27 B.C.E.–14 C.E.

In 27 B.C.E., Octavian proclaimed that he “gave back the state from [his] own power to the control of the Roman Senate and the people” and announced they should decide how to preserve it. Recognizing Octavian’s power, the senators asked him to safeguard the state, granted him special civil and military powers, and bestowed on him the honorary title Augustus, meaning “divinely favored.”

Augustus changed Rome’s political system, but he retained the name republic and maintained the appearance of representative government. Citizens elected consuls, the Senate gave advice, and the assemblies met. Augustus occasionally served as consul, but mostly he let others hold that office so they could enjoy its prestige. He concealed his monarchy by referring to himself only with the honorary title princeps, meaning “first man” (among social equals), a term of status from the republic. The Romans used the Latin word princeps to describe the position that we call emperor, and so the Roman government in the early empire after 27 B.C.E. is most accurately labeled the principate. Each new princeps was supposed to be chosen only with the Senate’s approval, but in practice each ruler chose his own successor, in the way a royal family decides who will be king. To preserve the tradition that no official should hold more than one post at a time, Augustus as princeps had the Senate grant him the powers, though not the office, of a tribune. In 23 B.C.E., the Senate agreed that Augustus should also have a consul’s power to command (imperium): in fact, his power would be superior to that held by the actual consuls.

Holding the power of a tribune and a power even greater than that of a consul meant that Augustus could rule the state without filling any formal executive political office. Augustus insisted that people obeyed him not out of fear but out of respect for his auctoritas (“moral authority”). Since Augustus realized that symbols affect people’s perception of reality, he dressed and acted modestly, like a regular citizen, not an arrogant king. Livia, his wife, played a prominent role as his political adviser and partner in publicly upholding old-fashioned values. In fact, Augustus and the emperors who came after him were able to exercise supreme power because they controlled the army and the treasury. Later Roman emperors held the same power but continued to refer to the state as the republic; the senators and the consuls continued to exist, and the rulers continued to pretend to respect them.

Augustus made the military the foundation of the emperor’s power by turning the republic’s citizen militia into a professional, full-time army and navy. He established regular lengths of service and retirement benefits, making the emperor the troops’ patron and solidifying their loyalty to him. To pay the added costs, Augustus imposed Rome’s first inheritance tax on citizens, angering the rich. He also stationed several thousand soldiers in Rome for the first time ever. These soldiers—the praetorian guard—would later play a crucial role in selecting the next emperor when the current one died. Augustus meant them to provide security for him and prevent rebellion in the capital by serving as a visible reminder that the superiority of the princeps was backed by the threat of armed force.

Augustus constantly promoted his image as patron and public benefactor. He used media as small as coins and as large as buildings. As a mass-produced medium for official messages, Roman coins functioned like modern political advertising. They proclaimed slogans such as “Father of His Country,” to stress Augustus’s moral authority, or “Roads have been built,” to emphasize his care for the public. (See “Document 6.1: Augustus, Res Gestae (My Accomplishments).”)

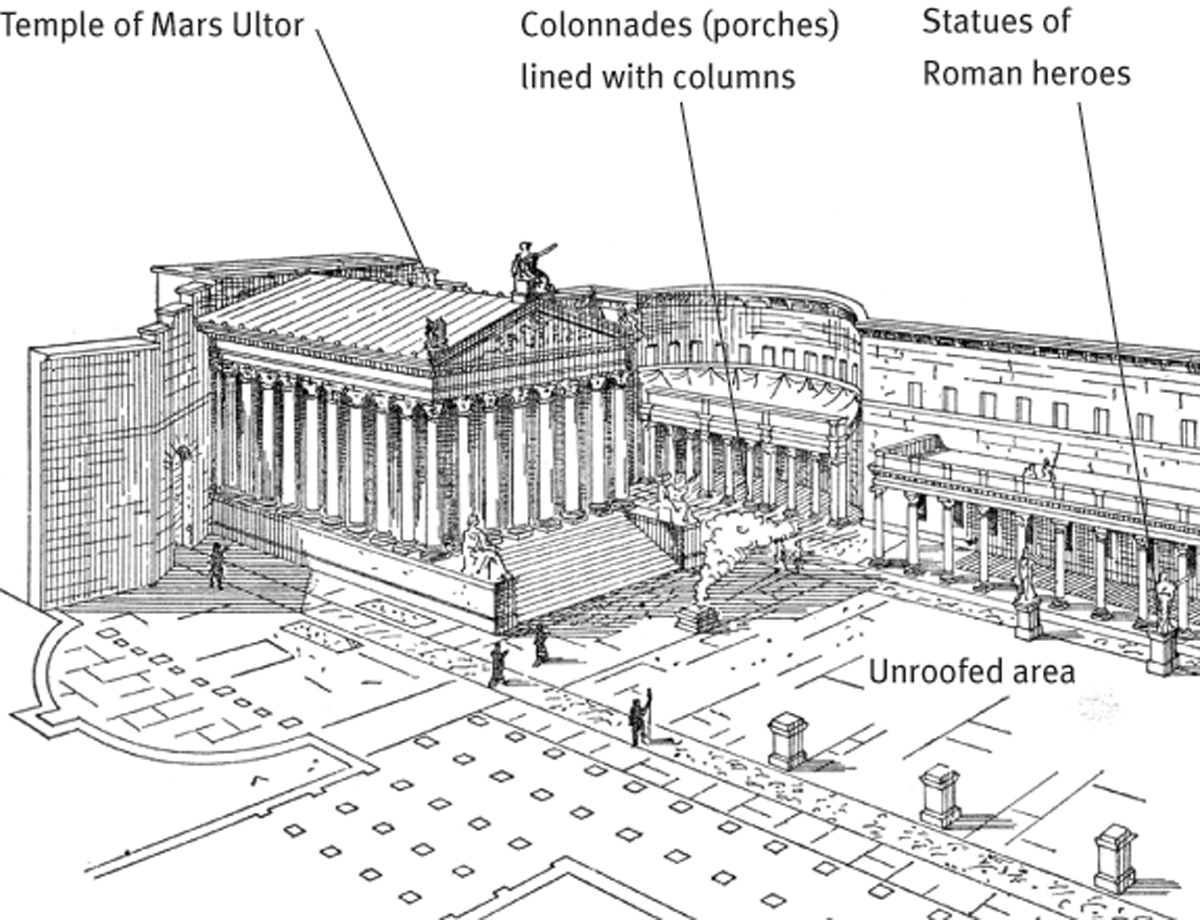

Augustus used his personal fortune to erect spectacular public buildings in Rome. The huge Forum of Augustus, dedicated in 2 B.C.E., best illustrates his skill at communicating messages through architecture (Figure 6.1). This public gathering space centered on a temple to Mars, the god of war. Two-story colonnades held statues of famous Roman heroes to serve as inspirations to the young. Augustus’s forum hosted religious rituals and the coming-of-age ceremonies of upper-class boys. As a symbol, it demonstrated his justifications for ruling: a new age of peace and security through military power, devotion to the gods protecting Rome, respect for tradition, and generosity in spending money on public works.

Augustus used the paternalism of the patron-client system to make the princeps everyone’s most important patron, possessing the moral authority to guide their lives. When in 2 B.C.E. the Senate and the people proclaimed Augustus “Father of His Country,” the title emphasized that the emperor governed like a father: stern but caring, expecting obedience and loyalty from his children, and taking care of them in return. The goal was stability and order, not freedom.

Augustus ruled until his death at age seventy-five in 14 C.E. As the historian Tacitus (c. 56–120 C.E.) remarked, by the time Augustus died after a reign of forty-one years, “almost no one was still alive who had seen the republic.” His longevity, military innovations, support for the masses, and manipulation of political symbols had allowed Augustus to create the Roman Empire.