Daily Life in the Rome of Augustus

Printed Page 178

Important EventsDaily Life in the Rome of Augustus

In Augustan Rome’s population of nearly one million, many had no regular jobs and too little to eat. The streets were packed: “One man jabs me with his elbow, another whacks me with a pole; my legs are smeared with mud, and big feet step on me from all sides,” one poet wrote of walking in Rome. To ease congestion in the narrow streets, the city banned wagons in the daytime.

Most residents lived in small apartments in multistoried buildings called islands. The first floors housed shops, bars, and restaurants. The higher the floor, the cheaper the rent. The wealthy, who lived at ground level, had piped-in water. The less fortunate had to fill water jugs at public fountains, to which aqueducts delivered fresh water, and then lug the heavy jugs up the stairs. Most people had to use the public latrines or keep buckets for toilets at home and then carry the waste down to the streets for sewage collectors. Sanitation was a problem in this city that generated sixty tons of human waste daily.

However, low fees for public baths meant that almost everyone could bathe regularly. Baths were centers for exercising and socializing. Bathers progressed through a series of increasingly warm areas until they reached a sauna-like room. They swam naked in their choice of either hot or cold pools. Men and women bathed apart. (See “Document 6.2: The Scene at a Roman Bath.”)

Augustus improved public safety and health. He instituted the first public fire department in Western history. He also established Rome’s first permanent police force. He greatly enlarged the city’s main sewer, but its contents still emptied untreated into the Tiber River. Also, poor people often left human and animal corpses in the streets, to be gnawed by birds and dogs. Flies and no refrigeration contributed to frequent gastrointestinal ailments. The wealthy splurged on luxuries such as snow rushed from the mountains to ice their drinks and slaves to clean their houses, which were built around courtyards and gardens. Roman architects built public structures with concrete, brick, and stone that lasted centuries, but crooked contractors cheated on materials for private buildings; therefore, apartment buildings sometimes collapsed. Augustus imposed a maximum height of seventy feet on new apartment buildings to limit the danger.

As the people’s patron, Augustus paid for grain to feed the poor, extending the government’s traditional distribution of food to 250,000 heads of households. From this grain, people made bread or soup, adding beans, leeks, or cheeses if they could afford them; they washed down these meals with cheap wine. The rich ate more costly food, such as roast pork or seafood with honey and vinegar sauce.

Wealthy Romans increasingly spent money on luxuries and political careers instead of raising families. Fearing the falling birthrate would destroy the social elite on whom Rome relied for public service, Augustus granted privileges to the parents of three or more children. He criminalized adultery, even exiling his own daughter—his only child—and a granddaughter for sex scandals. His legislation failed, however, and the prestigious old families dwindled over time. With each generation, three-quarters of senatorial families lost their official status by either spending all their money or dying off without having children. The emperors filled the open places in the social hierarchy and in the Senate with equites and provincials.

Since imperial Rome still gave citizenship to freed slaves, all slaves hoped someday to become a free Roman citizen, regardless of how they had originally become enslaved (by being captured in war, stolen from their home region by slave traders, or born to slave women as the owner’s property). Freed slaves’ descendants, if they became wealthy, could become members of the social elite. This policy of giving citizenship to former slaves meant that eventually most Romans had slave ancestors.

The harshness of slaves’ lives varied widely. Slaves in agriculture and manufacturing had a grueling existence, while household slaves lived more comfortably. Modestly prosperous families owned one or two slaves, while rich houses and the imperial palace owned large numbers. Domestic slaves were often women, working as nurses, maids, kitchen helpers, and clothes makers. Some male slaves ran businesses for their masters and were often allowed to keep part of the profits, which they could save to purchase their freedom. Women had less opportunity to earn money, though masters sometimes granted tips for sexual favors to both female and male slaves. Many female prostitutes were slaves working for their owner in a brothel. Slaves with savings would sometimes buy other slaves, especially to have a mate; they were barred from legal marriage, because they and their children remained their master’s property, but they could live as a shadow family. Some masters’ tomb inscriptions express affection for a slave, but if slaves attacked their owner, the punishment was death.

Violence featured in much of Roman public entertainment. The emperors provided shows featuring hunters killing wild beasts, animals mangling condemned criminals, mock naval battles in flooded arenas, gladiatorial combats, and wreck-filled chariot races. Spectators were seated according to their social rank and gender. The emperor and senators sat up front, while women and the poor were in the upper tiers.

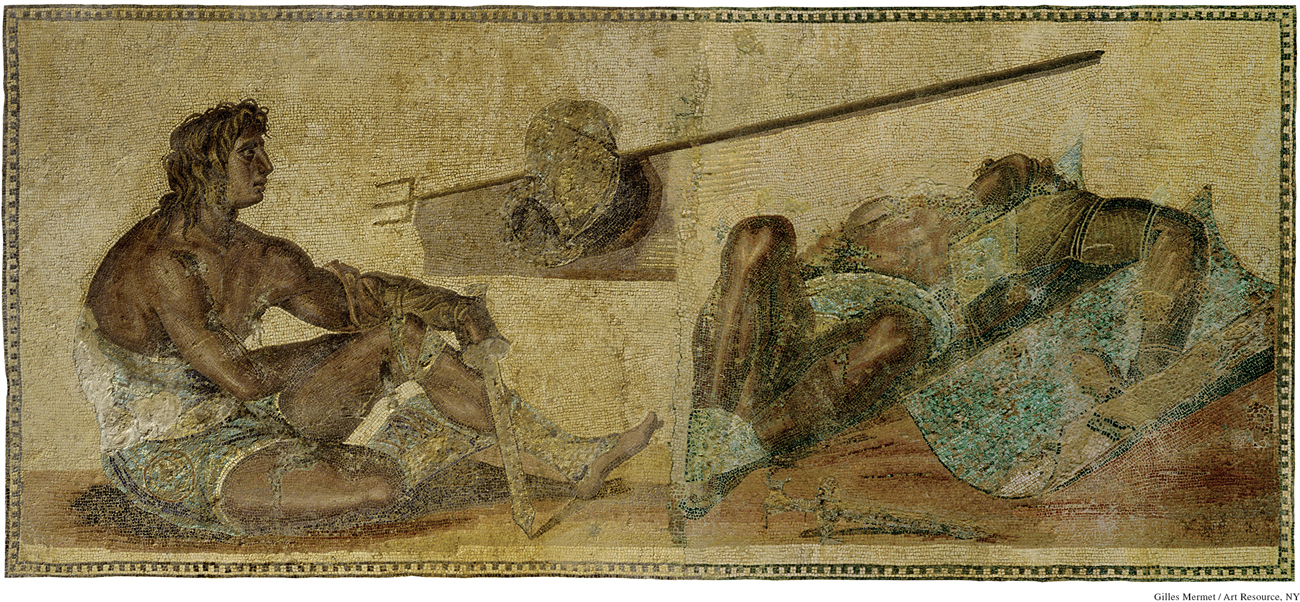

Criminals and slaves could be forced to fight as gladiators, but free people also voluntarily competed, hoping to become celebrities and win prizes. Most gladiators were men, though women could fight other women until such matches were banned around 200 C.E. Gladiators were often wounded or killed in the fights, but their contests rarely required a fight to the death, unless they were captives or criminals. To make the bouts unpredictable, pairs of gladiators often competed with different weapons. One favorite match pitted a lightly armored “net man” with a net and a trident against a heavily armored “fish man,” so named from his helmet design. Betting was popular, and the crowds were rowdy.

Public entertainment supported communication between the ruler and the ruled. Emperors provided gladiatorial combats, chariot races, and theater productions for the masses, and ordinary citizens staged protests at them to express their wishes. Poor Romans, for example, rioted to protest shortfalls in the free grain supply.