The Abbasid Caliphate, 750–936

Printed Page 285

Important EventsThe Abbasid Caliphate, 750–936

In 750, a civil war ousted the Umayyads and raised the Abbasids to the caliphate. The Abbasids found support in an uneasy coalition of Shi‘ites (the faction of Islam loyal to Ali’s memory) (See “The Caliphs, Muhammad’s Successors, 632-750” in Chapter 8) and non-Arabs who had been excluded from the Umayyad government. Under the Abbasids, the center of Islamic rule shifted from Damascus, with its roots in the Roman tradition, to the newly founded city of Baghdad in Iraq. Here the Abbasid caliphs adhered even more firmly than the Umayyads to Persian courtly models, with a centralized administration, a large staff, and control over the appointment of regional governors.

The Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809) presided over a flourishing empire. His contemporary Frankish ruler, Charlemagne, was impressed with the elephant Harun sent him as a gift, along with monkeys, spices, and medicines. Such items were mainstays of everyday commerce in Harun’s Iraq. A mid-ninth-century catalog of imports listed “tigers, panthers, elephants, panther skins, rubies, white sandal[wood], ebony, and coconuts” from India as well as “silk, chinaware, paper, ink, peacocks, racing horses, saddles, felts [and] cinnamon” from China.

The Abbasid dynasty began to decline after Harun’s death. While his sons waged war against each other, the caliphs lost control over many regions, including Syria and Egypt. They needed to recruit an army that would be loyal to them alone. This they found in “outsiders,” many of them Turks from east of the Caspian Sea (today Kazakhstan). Many of the Turks, later called Mamluks, were bought as slaves. Once purchased, the Turks were freed and paid a salary. They were expert fighters, but the Abbasids needed a good tax base to be able to pay them. This they did not have. Serious uprisings just south of Baghdad kept huge swaths of territory outside the control of the caliphs. Other regions of the Islamic world easily went their own way when the caliphs lacked the money to keep them in line. In the tenth century, the caliphs became figureheads only, while independent regional rulers collected taxes and hired their own armies.

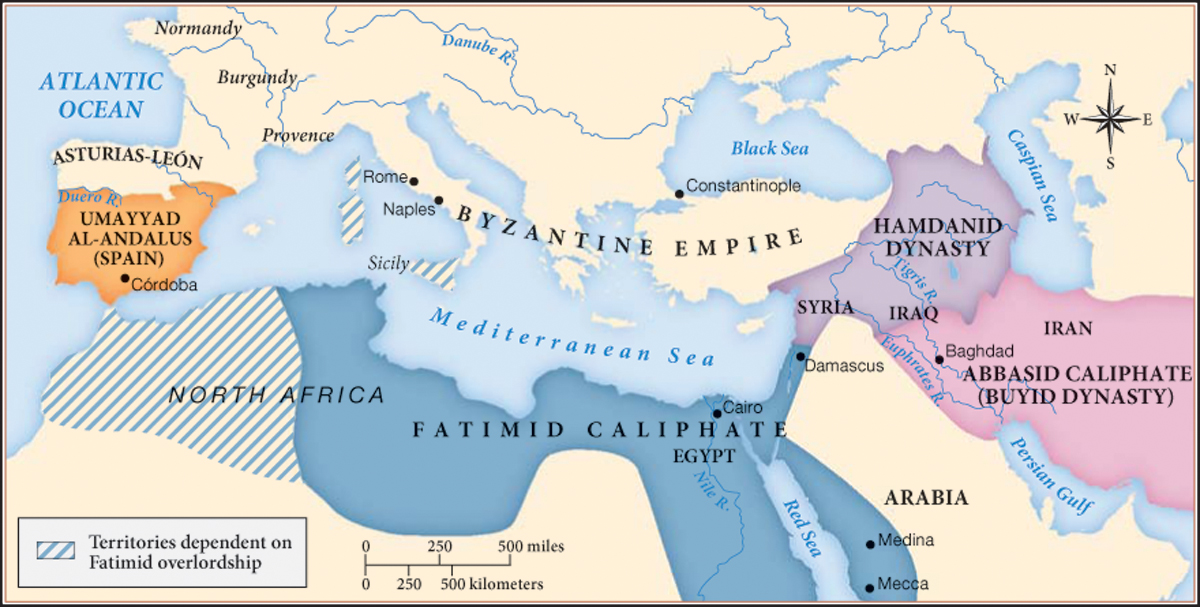

Thus, in the Islamic world, as in the Byzantine, new regional lords challenged the power of the central ruler. But the process advanced more quickly in Islamic than in Byzantine territories. Map 9.1 correctly omits any indication of regional dynatoi because the key center of power in the Byzantine Empire continued to be Constantinople. Map 9.2, in contrast, shows how the Abbasid caliphate fragmented as local dynasties established themselves.