New Monastic Orders of Poverty

Printed Page 329

Important EventsNew Monastic Orders of Poverty

Like the popes, the monks of Cluny and other Benedictine monasteries were reformers. Unlike the popes, they spent nearly their entire day in large and magnificently outfitted churches singing a long and complex liturgy consisting of Masses, prayers, and psalms. These “black monks”—so called because they dyed their robes black—reached the height of their popularity in the eleventh century. Their monasteries often housed hundreds of monks, though convents for Benedictine nuns were usually less populated. Cluny was one of the largest monasteries, with some four hundred brothers in the mid-eleventh century.

In the twelfth century, the black monks’ lifestyle came under attack by groups seeking a religious life of poverty. They considered the opulence of a huge and gorgeous monastery like Cluny to be a sign of greed rather than honor. The Carthusian order founded by Bruno of Cologne in the 1080s was one such group. Each monk took a vow of silence and lived as a hermit in his own small hut. Monks occasionally joined others for prayer in a common prayer room, or oratory. When not engaged in prayer or meditation, the Carthusians copied manuscripts. They considered this task part of their religious vocation, a way to preach God’s word with their hands rather than their mouths. The Carthusian order grew slowly. Each monastery was limited to only twelve monks, the number of the Apostles.

The Cistercians, by contrast, expanded rapidly. Their guiding spirit was St. Bernard (c. 1090–1153), who arrived at the Burgundian monastery of Cîteaux (in Latin, Cistercium, hence the name of the monks) in 1112 along with about thirty friends and relatives. St. Bernard soon became abbot of Clairvaux, one of a cluster of Cistercian monasteries in Burgundy. By the mid-twelfth century, more than three hundred monasteries spread throughout Europe were following what they took to be the customs of Cîteaux. Nuns, too—as eager as monks to live the life of simplicity and poverty that they believed the Apostles had enjoyed and endured—adopted Cistercian customs. By the end of the twelfth century, the Cistercians were an order: all of their houses followed rules determined at the General Chapter, a meeting at which the abbots met to hammer out legislation.

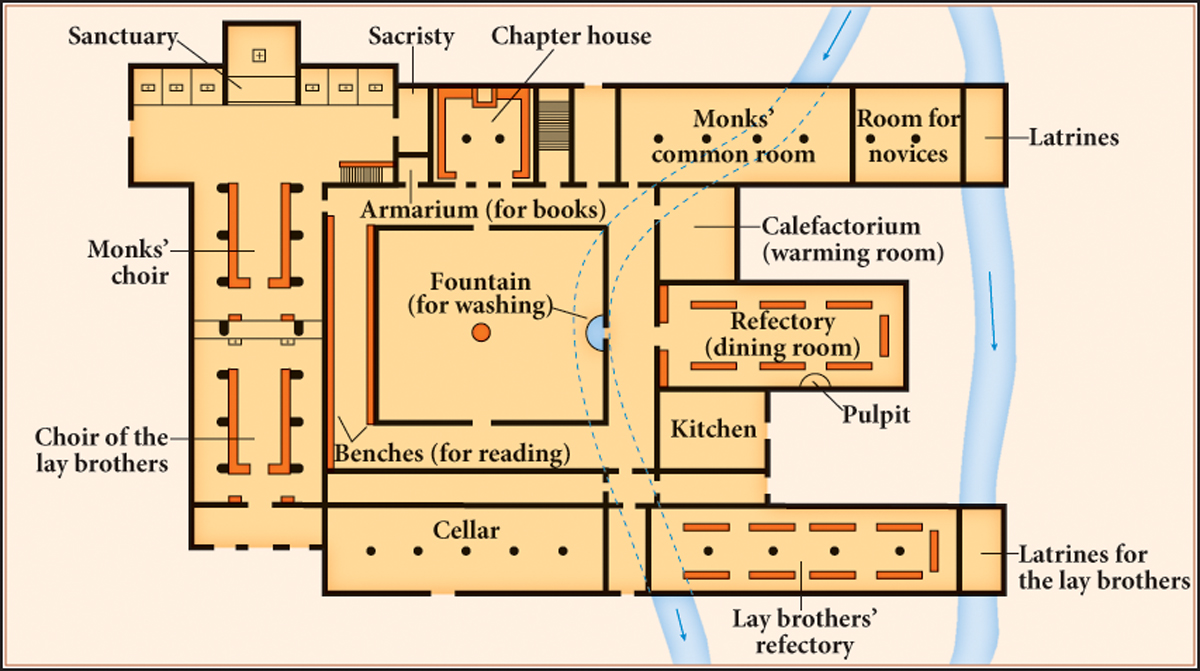

Although they held up the rule of St. Benedict as the foundation of their monastic life, the Cistercians created a lifestyle all their own, largely governed by the goal of simplicity. Rejecting even the conceit of blackening their robes, they left them undyed (hence their nickname, the “white monks”). As shown in Figure 10.1, a diagram of Fountains Abbey in England, their monasteries were divided into two parts: the eastern half was for the monks, and the western half was for the lay brothers. The lay brothers did the hard manual labor necessary to keep the other monks—the “choir” monks—free to worship.

Cistercian churches reflected the order’s emphasis on poverty. The churches were small, made of smoothly hewn, undecorated stone. Wall paintings and sculpture were prohibited. Their buildings cultivated a quiet beauty. Cistercian churches were bright, cool, and serene.

The white monks dedicated themselves to monastic administration as well as to private prayer and contemplation. Each house had large and highly organized farms and grazing lands called granges. Cistercian monks spent much of their time managing their estates and flocks, both of which were yielding handsome profits by the end of the twelfth century. Although they had reacted against the wealth of the commercial revolution, the Cistercians became part of it, and managerial expertise was an integral part of their monastic life.

At the same time, the Cistercians emphasized a spirituality of intense emotion. They cultivated a theology that stressed the humanity of Christ and Mary. They regularly used maternal metaphors to describe the nurturing care that Jesus provided to humans. The Cistercian Jesus was approachable, human, protective, even mothering.

REVIEW QUESTION What were the causes and consequences of the Gregorian reform?

Many who were not members of the Cistercian order held similar views of God; their spirituality signaled wider changes. For example, around 1099, St. Anselm wrote a theological treatise entitled Why God Became Man, arguing that since man had sinned, only a sinless man could redeem him. St. Anselm’s work represented a new theological emphasis on the redemptive power of human charity, including that of Jesus as a human being. As Anselm was writing, the crusaders were heading for the very place of Christ’s crucifixion, making his humanity more real and powerful to people who walked in the holy “place of God’s humiliation and our redemption,” as one chronicler put it. Yet this new stress on the loving bonds that tied Christians together also led to the persecution of non-Christians, especially Jews and Muslims.