France: Consolidation and Conquest

Printed Page 359

Important EventsFrance: Consolidation and Conquest

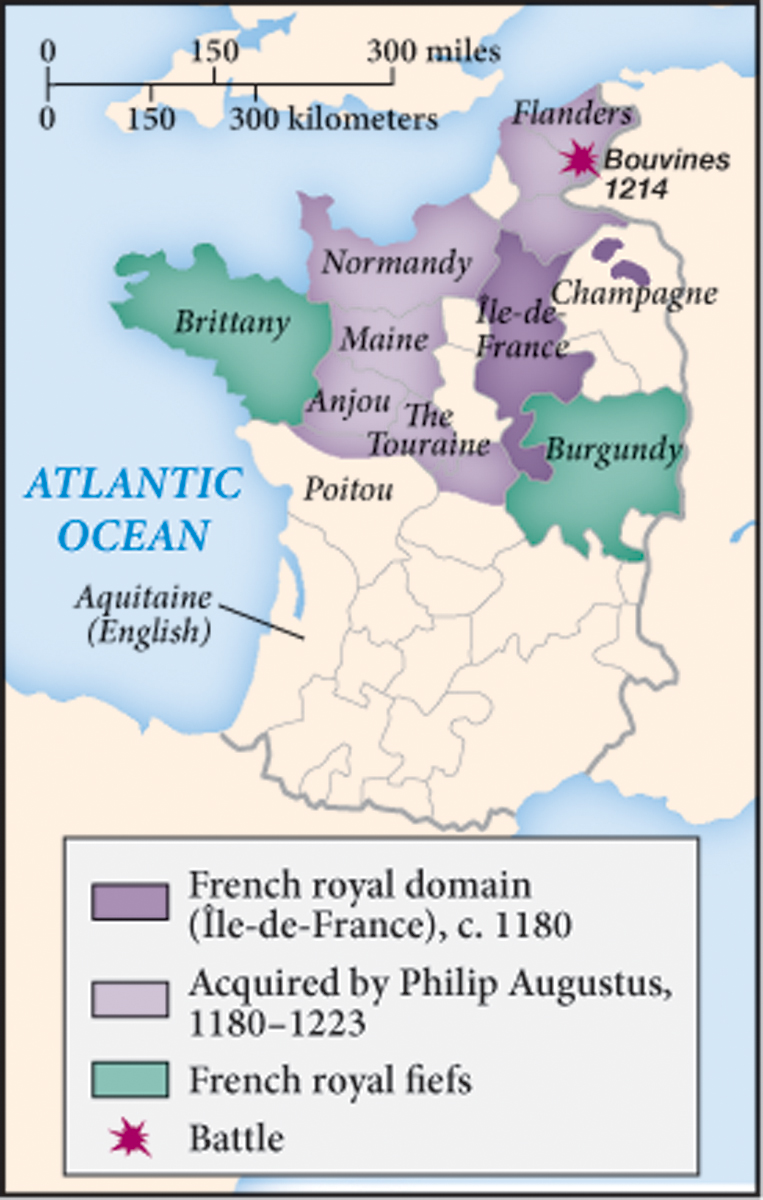

John’s territorial loss was the gain of the French king Philip II (Philip Augustus) (r. 1180–1223). When Philip came to the throne, the royal domain, the Île-de-France, was sandwiched between territory controlled by the counts of Flanders, Champagne, and Anjou. King Henry II and the counts of Flanders and Champagne vied to control the young king. Philip, however, quickly learned to play the three rulers against one another. Contemporaries were astounded when Philip successfully gained territory: he wrested land from Flanders in the 1190s and then, as we have seen, he took Normandy, Anjou, Maine, the Touraine, and Poitou from King John of England in 1204. No wonder he was given the epithet Augustus, after the first Roman emperor.

After Philip’s army confirmed its triumph over most of John’s continental territories in 1214, the French monarch could boast that he was the richest and most powerful ruler in France. Most important, Philip had sufficient support and resources to keep a tight hold on Normandy.* He received homage and fealty from most of the Norman aristocracy, and his officers carried out their work there in accordance with Norman customs.

Wherever he ruled, Philip instituted new administrative practices. Before Philip’s day, most French royal arrangements were committed to memory rather than to writing. If decrees were recorded at all, they were saved by the recipient, not by the government. The king did keep some documents, which he generally carried with him in his travels like personal possessions. But in a battle in 1194, Philip lost his meager cache of documents along with much treasure when he had to abandon his baggage train. After 1194, the king had all his decrees written down, and he established a permanent repository in which to keep them. (See “Taking Measure: The Bureaucratization of the French Monarchy.”)

Like the English king, Philip relied largely on members of the lesser nobility—knights and clerics, many of whom were masters educated in the city schools of France. They served as officers of his court, tax collectors, and overseers of the royal estates, making the king’s power felt locally as never before.