Powerful States in Western Europe

Printed Page 430

Important EventsPowerful States in Western Europe

Four powerful states dominated western Europe during the fifteenth century: Spain, the duchy of Burgundy, France, and England. By the end of the century, however, Burgundy had disappeared, leaving three exceptionally powerful monarchies.

The kingdom of Spain was created by marriage. Decades of violence on the Iberian peninsula ended when Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon married in 1469 and restored law and order in the decades that followed. Castile was the powerhouse, with Aragon its lesser neighbor and Navarre a pawn between the two. When the king and queen joined forces, they ruled together over their separate dominions, allowing each to retain its traditional laws and privileges. The union of Castile and Aragon was the first step toward a united Spain and a centralized monarchy there.

Relying on a lucrative taxation system, pliant meetings of the cortes (the representative institution that voted on taxes), and an ideology that glorified the monarchy, Ferdinand and Isabella consolidated their power. They had an extensive bureaucracy for financial matters and a well-staffed writing office. They sent their own officials to rule over towns that had previously been self-governing, and they established regional courts of law.

Created, like Spain, by marriage, the duchy of Burgundy was disunited linguistically and geographically. Through purchases, inheritance, and conquests, the dukes ruled over French-, Dutch-, and German-speaking subjects, creating a state that resembled a patchwork of provinces and regions, each jealously guarding its laws and traditions. The Low Countries, with their flourishing cities, constituted the state’s economic heartland, while the region of Burgundy itself, which gave the state its name, offered rich farmlands and vineyards. Unlike England, whose island geography made it a natural political unit; or France, whose borders were forged in the national experience of repelling English invaders; or Spain, whose national identity came from centuries of warfare against Islam, Burgundy was an artificial creation whose coherence depended entirely on the skillful exercise of statecraft.

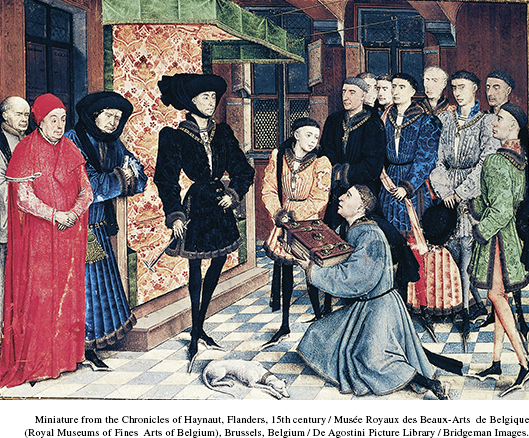

At the heart of Burgundian politics was the personal cult of its dukes. Philip the Good (r. 1418–1467) and his son Charles the Bold (r. 1467–1477) were very different kinds of rulers, but both were devoted to enhancing the prestige of their dynasty and the security of their dominion. Philip was a lavish patron of the arts who commissioned numerous illuminated manuscripts, chronicles, tapestries, paintings, and music in his efforts to glorify himself as ruler of Burgundy.

The Burgundians’ success depended in large part on their personal relationship with their subjects. Not only did the dukes travel constantly from one part of their dominion to another, but they also staged elaborate ceremonies to enhance their power and promote their legitimacy. Their entries into cities and their presence at weddings, births, and funerals became the centerpieces of a “theater state” in which the dynasty provided the only link among diverse territories. (See “Document 13.2: The Ducal Entry into Ghent.”) New rituals became propaganda tools. Philip’s revival of chivalry at court transformed the semi-independent nobility into courtiers closely tied to the prince. But, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, (See “The Hundred Years War, 1337-1453.”) when Charles the Bold died in 1477, the duchy was parceled out to France and the Holy Roman Empire.

It was its quick recovery from the Hundred Years’ War that allowed France to take a large bite out of Burgundy. Under Louis XI (r. 1461–1483), the French monarchy both expanded its territory and consolidated its power. Soon after Burgundy fell, Louis inherited most of southern France. When he inherited claims to the duchy of Milan and the kingdom of Naples, he was ready to exploit other opportunities in Italy. By the end of the century, France had doubled its territory, assuming boundaries close to its modern ones, and was looking to expand even further.

To strengthen royal power at home, Louis promoted industry and commerce, imposed permanent salt and land taxes, maintained western Europe’s first standing army (created by his predecessor), and dispensed with the meetings of the Estates General, which included the clergy, the nobility, and representatives from the major towns of France. The French kings had already increased their power with important concessions from the papacy. The Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges (1438) asserted the superiority of a general church council over the pope. Harking back to a long tradition of the high Middle Ages, the Pragmatic Sanction established what would come to be known as Gallicanism (after Gaul, the ancient Roman name for France), in which the French king would effectively control ecclesiastical revenues and the appointment of French bishops.

England, too, recovered quickly from civil wars—called the Wars of the Roses—spawned by the stresses of the Hundred Years’ War and concluded with the victory of Henry Tudor, who took the title of Henry VII (r. 1485–1509). Despite the Wars of the Roses, which affected mainly the English nobility, the English economy continued to grow during the fifteenth century. The cloth industry expanded considerably, and the English used much of the raw wool that they had been exporting to the Low Countries to manufacture goods at home. London merchants, taking a vigorous role in trade, also assumed greater political prominence, not only in governing London but also in serving as bankers to kings and members of Parliament. In the countryside the landed classes—the nobility, the gentry (the lesser nobility), and the yeomanry (free farmers)—benefited from rising farm and land-rent income as the population increased slowly but steadily. The Tudor monarchs took advantage of the general prosperity to bolster both their treasury and their power.