The Invention of Printing

Printed Page 447

Important EventsThe Invention of Printing

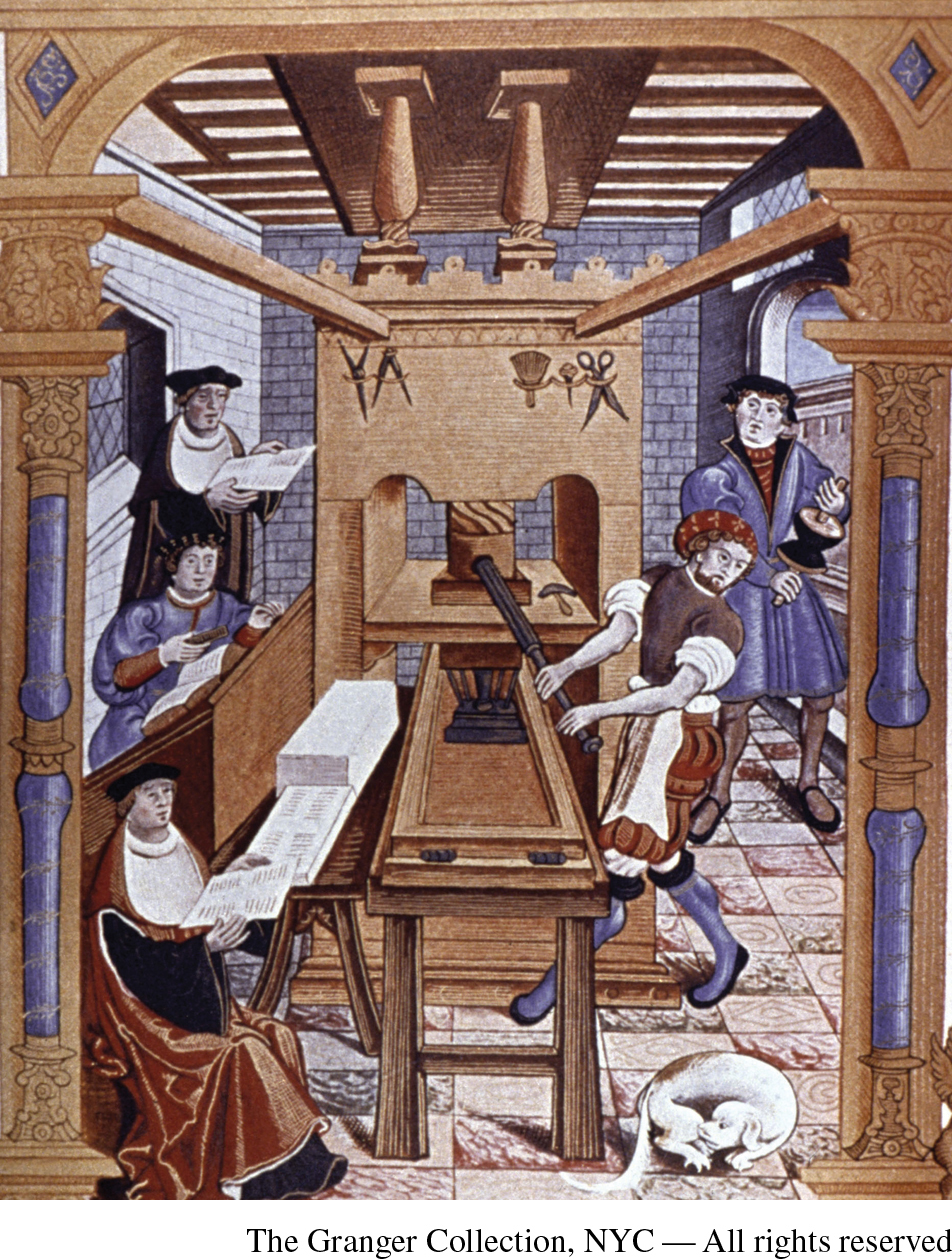

Printing with movable type, first developed in Europe in the 1440s by Johannes Gutenberg, a German goldsmith, marked a revolutionary departure from the old practice of copying works by hand or stamping pages with individually carved woodblocks. The Chinese invented movable type in the eleventh century, but they preferred woodblock printing because it was more suitable to the Chinese language, with its thousands of different characters. In Europe, with only twenty-six letters to the alphabet, movable type allowed entire manuscripts to be printed more quickly than ever before. Single letters, made in metal molds, could be emptied out of a frame and new ones inserted to print each new page.

In 1467, two German printers established the first press in Rome; within five years, they had produced twelve thousand volumes, a feat that in the past would have required a thousand scribes working full-time. Printing also depended on the large-scale production of paper. Papermaking came to Europe from China via Arab intermediaries. By the fourteenth century, paper mills in Italy were producing paper that was more fragile but also much cheaper than parchment or vellum, the animal skins that Europeans had previously used for writing. (See “Taking Measure: The Printing Press in Europe, ca. 1500.”) Early printed books attracted an elite audience. Their expense made them inaccessible to most literate people, who comprised a minority of the population in any case. Gutenberg’s famous two-volume Latin Bible was a luxury item, and only 185 copies were printed. Gutenberg Bibles remain today a treasure that only the greatest libraries possess.

The invention of mechanical printing dramatically increased the speed at which people could transmit knowledge, and it freed individuals from having to memorize everything they learned. Printed books and pamphlets, even one-page flyers, would create a wide community of scholars no longer dependent on personal patronage or church sponsorship for texts. Printing thus encouraged the free expression and exchange of ideas, and its disruptive potential did not go unnoticed by political and religious authorities. Rulers and bishops in the German states, the birthplace of the printing industry, moved quickly to issue censorship regulations, but their efforts could not prevent the outbreak of the Protestant Reformation.