New Forms of Discipline

Printed Page 457

Important EventsNew Forms of Discipline

Faced with the social firestorms ignited by religious reform, the middle-class urbanites who supported the Protestant Reformation urged greater religious conformity and stricter moral behavior. Protestants did not have monasteries or convents or saints’ lives to set examples; they sought moral examples in their own homes, in the sermons of their preachers, and in their own reading of the Bible. Some of these attitudes had medieval roots, yet the Protestant Reformation fostered their spread and Catholics soon began to embrace them.

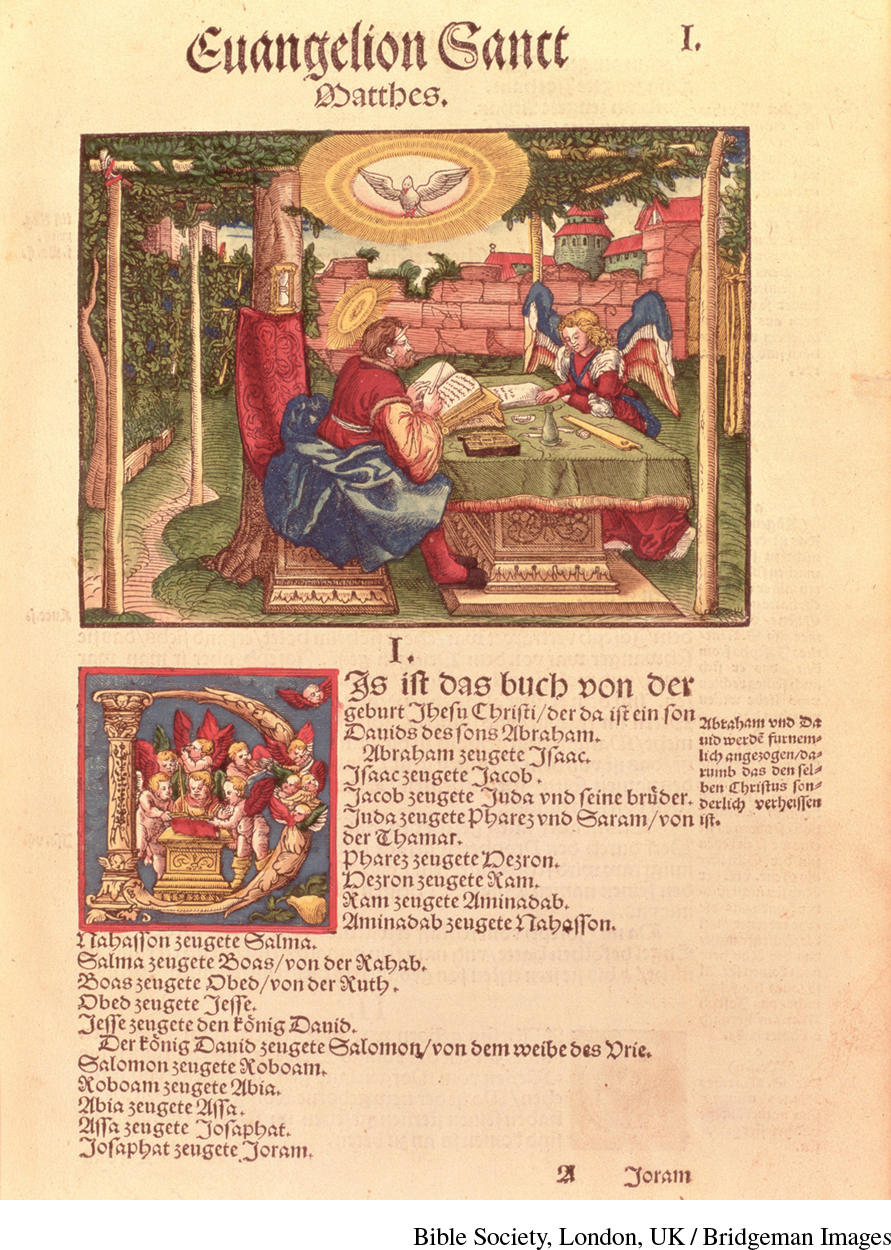

Although the Bible had been translated into German before, Luther’s translations (of the New Testament in 1522 and of the Old Testament in 1534) quickly became authoritative. A new Bible-centered culture began to take root, as more than 200,000 copies of Luther’s New Testament were printed over twelve years, an immense number for the time. Peppered with witty phrases and colloquial expressions, Luther’s Bible not only made the sacred writings more accessible to ordinary people but also helped standardize the German language. Bible reading became a common pastime undertaken in solitude or at family and church gatherings. To counter Protestant success, Catholic German Bibles soon appeared, thus sanctioning Bible reading by the Catholic laity, a sharp departure from medieval church practice.

The new emphasis on self-discipline led to growing impatience with the poor. Between 1500 and 1560, rapid economic and population growth created prosperity for some and stress—heightened by increased inflation—for many. Wanderers and urban beggars were by no means novel, but now moralists, both Catholic and Protestant, denounced vagabonds as lazy and potentially criminal.

The Reformation provided an opportunity to restructure relief for the poor. Instead of decentralized, private initiatives often overseen by religious orders, Protestant magistrates appointed officials to head urban agencies that would certify the genuine poor and distribute welfare funds to them. Catholic authorities did the same. In 1531, Henry VIII asked justices of the peace (unpaid local magistrates) to license the poor in England and to differentiate between those who could work and those who could not. In 1540, Charles V imposed a welfare tax in Spain to augment that country’s inadequate system of private charity.

In their effort to establish order and discipline, Protestant reformers denounced sexual immorality and glorified the family. The early Protestant reformers like Luther championed the end of clerical celibacy and embraced marriage. Luther, once a celibate priest himself, married a former nun. Protestant magistrates closed brothels and established marriage courts to handle disputes over marriage promises, child support, and divorce (allowed by Protestants in some rare situations). The magistrates also levied fines or ordered imprisonment for violent behavior, fornication, and adultery.

Prior to the Reformation, despite the legislation of church councils, marriages had largely been private affairs between families; some couples never even registered with the church. The Catholic church recognized any promise made between two consenting adults (with the legal age of twelve for females, fourteen for males) in the presence of two witnesses as a valid marriage. As the Reformation took hold, Protestants asserted government control over marriage, and Catholic governments followed suit. A marriage was legitimate only if registered by both a government official and a member of the clergy.