Dutch Revolt against Spain

Printed Page 476

Important EventsDutch Revolt against Spain

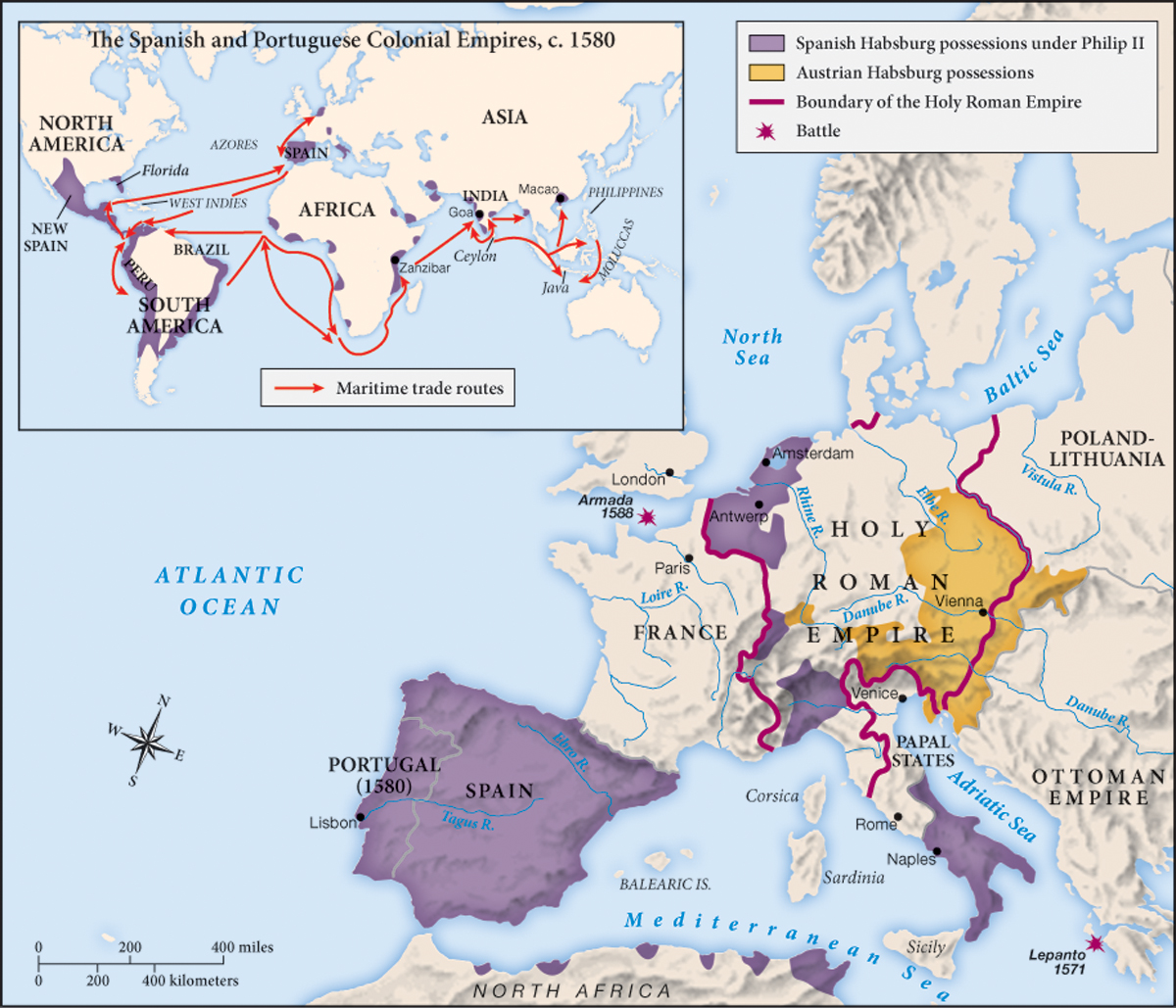

Although he failed to prevent Henry IV from taking the French throne in 1589, Philip II of Spain (r. 1556–1598) was the most powerful ruler in Europe (Map 15.1). In addition to the western Habsburg lands in Spain and the Netherlands, Philip had inherited from his father, Charles V, all the Spanish colonies recently settled in the New World of the Americas. Gold and silver funneled from the colonies supported his campaigns against the Ottoman Turks and the French and the English Protestants. But all the money of the New World could not prevent Philip’s eventual defeat in the Netherlands, where Calvinist rebels established the independent Dutch Republic, which soon vied with Spain, France, and England for commercial supremacy.

A deeply devout Catholic, Philip II came to the Spanish throne at age twenty-eight determined to restore Catholic unity in Europe and lead the Christian defense against the Muslims. His brief marriage to Mary Tudor (Mary I of England) did not produce an heir, but it and his subsequent marriage to Elisabeth de Valois, the sister of Charles IX and Henry III of France, gave him reason enough for involvement in English and French affairs. In 1578, the king of Portugal died fighting Muslims in Morocco, and two years later Philip took over this neighboring realm with its rich empire in Africa, India, and the Americas.

Philip insisted on Catholic unity in the lands under his control and worked to forge an international Catholic alliance against the Ottoman Turks. In 1571, he achieved the single greatest military victory of his reign when he joined with Venice and the papacy to defeat the Turks in a great sea battle off the Greek coast at Lepanto. Seventy thousand sailors and soldiers fought on the allied side, and eight thousand died. The Turks lost twenty thousand men.

Spain now controlled the western Mediterranean but could not pursue its advantage because of threats elsewhere. Between 1568 and 1570, the Moriscos—Muslim converts to Christianity who remained secretly faithful to Islam—had revolted in the south of Spain, killing ninety priests and fifteen hundred Christians. Philip retaliated by forcing fifty thousand Moriscos to leave their villages and resettle in other regions. In 1609, his successor, Philip III, ordered their expulsion from Spanish territory, and by 1614 some 300,000 Moriscos had been forced to relocate to North Africa.

The Calvinists of the Netherlands were less easily intimidated: they were far from Spain and accustomed to being left alone. After the Spanish Fury of 1576 outraged Calvinists and Catholics alike, Prince William of Orange (whose name came from the lands he owned in southern France) led the Netherlands’ seven predominantly Protestant northern provinces into a military alliance with the ten mostly Catholic southern provinces and drove out the Spaniards. The Catholic southern provinces returned to the Spanish fold in 1579. Despite the assassination in 1584 of William of Orange, Spanish troops never regained control in the north. Spain would not formally recognize Dutch independence until 1648, but by the end of the sixteenth century the Dutch Republic (sometimes called Holland after the most populous of its seven provinces) was a self-governing state sheltering a variety of religious groups.

Religious toleration in the Dutch Republic developed for pragmatic reasons: the central government did not have the power to enforce religious orthodoxy. Each province governed itself and sent delegates to the one common institution, the States General. Although the princes of Orange resembled a ruling family, their powers paled next to those of local elites, known as regents. One-third of the Dutch population remained Catholic, and local authorities allowed them to worship as they chose in private. The Dutch Republic also had a relatively large Jewish population because many Jews had settled there after being driven out of Spain and Portugal. From 1597, Jews could worship openly in their synagogues. This openness to various religions would help make the Dutch Republic one of Europe’s chief intellectual and scientific centers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Well situated for maritime commerce, the Dutch Republic developed a thriving economy based on shipping and shipbuilding. Dutch merchants favored free trade in Europe because they could compete at an advantage. After the Dutch gained independence, Amsterdam became the main European money market for two centuries. The Dutch controlled many overseas markets thanks to their preeminence in seaborne commerce: by 1670, the Dutch commercial fleet was larger than the English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Austrian fleets combined.