The Dutch Republic

Printed Page 521

Important EventsThe Dutch Republic

When the Dutch Republic gained formal independence from Spain in 1648, it had already established a decentralized, constitutional state. Rich merchants called regents effectively controlled the internal affairs of each province and (through the Estates General) chose the stadholder, the executive officer responsible for defense and for representing the state at all ceremonial occasions. They almost always picked one of the princes of the house of Orange, but the stadholder resembled a president more than a king.

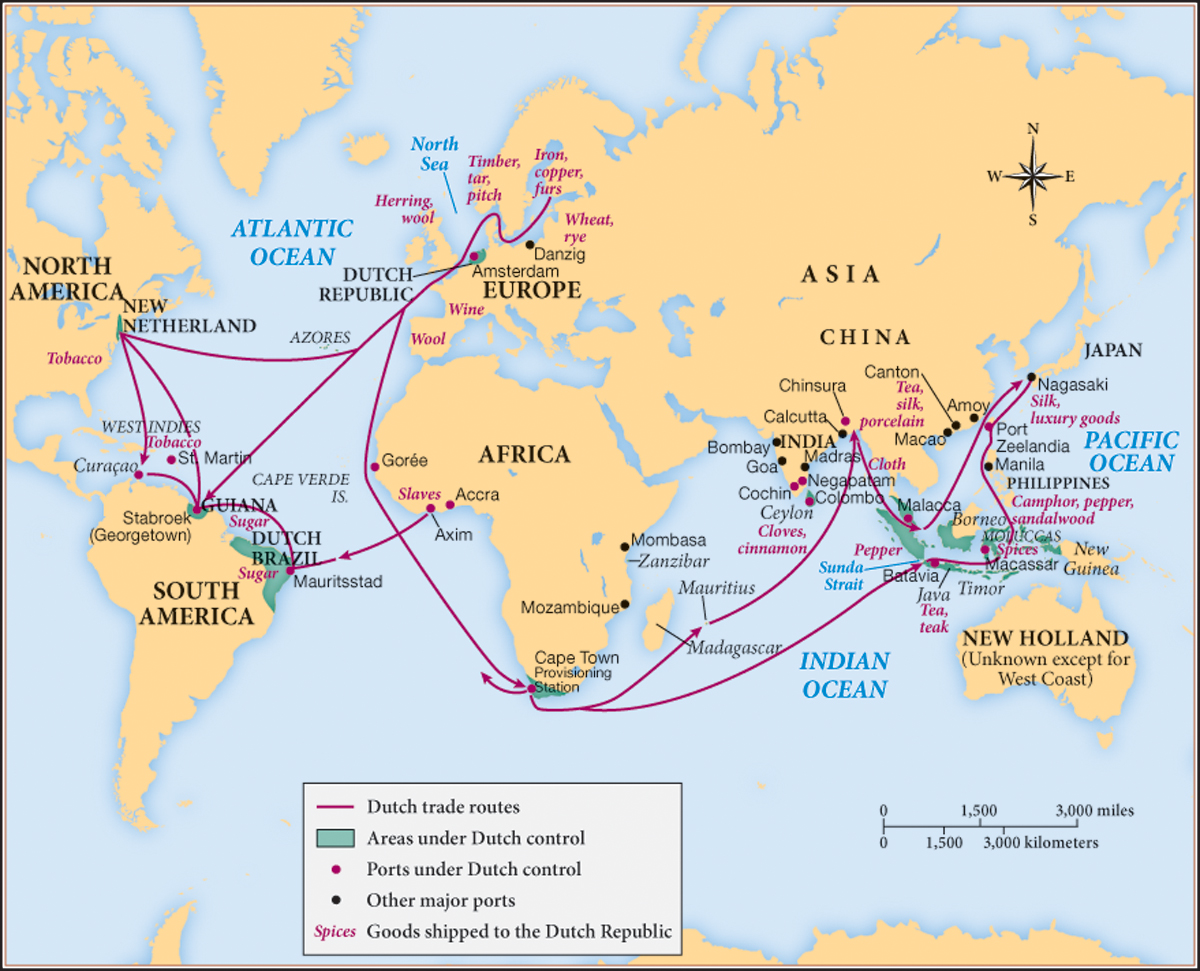

The Dutch Republic soon became Europe’s financial capital. Praised for their industriousness, thrift, and cleanliness—and maligned as greedy, dull, and fat—the Dutch dominated overseas commerce with their shipping (Map 16.2). They imported products from all over the world: spices, tea, and silk from Asia; sugar and tobacco from the Americas; wool from England and Spain; timber and furs from Scandinavia; grain from eastern Europe. A widely reprinted history of Amsterdam that appeared in 1662 described the city as “risen through the hand of God to the peak of prosperity and greatness. . . . The whole world stands amazed at its riches and from east and west, north and south they come to behold it.”

The Dutch rapidly became the most prosperous and best-educated people in Europe. Whereas in other countries kings, nobles, and churches bought art, in the Dutch Republic art buyers were merchants, artisans, and shopkeepers. One foreigner commented that “pictures are very common here, there being scarce an ordinary tradesman whose house is not decorated with them.” Relative prosperity decreased the need for married women to work, so Dutch society developed the clear contrast between middle-class male and female roles that would become prevalent elsewhere in Europe and in America more than a century later.

Extraordinarily high levels of urbanization and literacy created a large reading public. Dutch presses printed books censored elsewhere, and the University of Leiden attracted students and professors from all over Europe. Dutch tolerance extended to the works of Benedict Spinoza (1633–1677), a Jewish philosopher and biblical scholar who was expelled by his synagogue for alleged atheism but left alone by the Dutch authorities. Spinoza strove to reconcile religion with science and mathematics, but his work scandalized many Christians and Jews because he seemed to equate God and nature. Like nature, Spinoza’s God followed unchangeable laws and could not be influenced by human actions, prayers, or faith.

The Dutch lived, however, in a world of international rivalries in which strong central authority gave their enemies an advantage. The naval wars with England between 1652 and 1674 and the land wars with France, which lasted until 1713, drained the state’s revenues. The Dutch survived these direct military challenges but began to lose their position in international trade as both the British and French limited commerce with their own colonies to merchants from their own nations. At the end of the seventeenth century, as the Dutch elites became more preoccupied with ostentation, the Dutch “golden age” came to an end.