Slavery and the Atlantic System

Printed Page 542

Important EventsSlavery and the Atlantic System

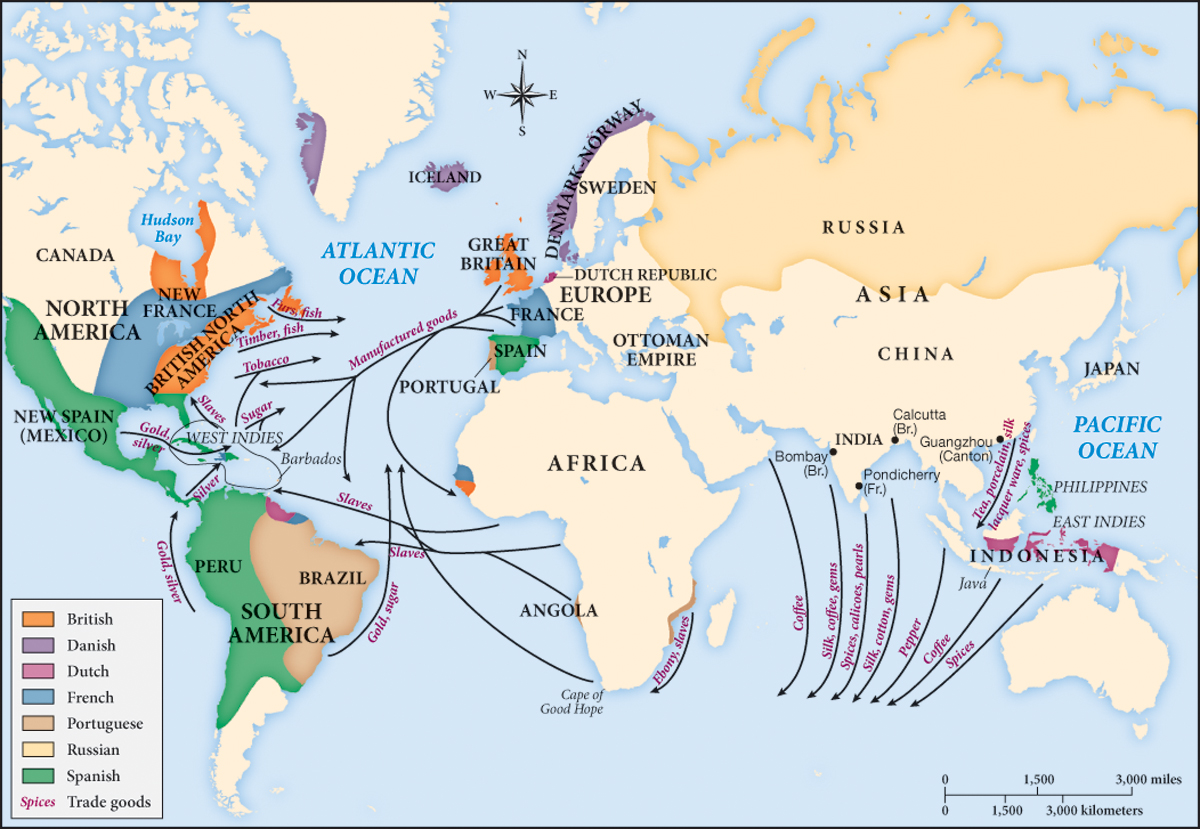

In the eighteenth century, European trade in the Atlantic rapidly expanded and became more systematically interconnected (Map 17.1). By 1650, Portugal had already sent forty thousand African slaves to Brazil to work on the new plantations, which were producing some fifteen thousand tons of sugar a year. A plantation was a large tract of land that produced a staple crop such as sugar, coffee, or tobacco; was farmed by slave labor; and was owned by a colonial settler from western Europe.

Realizing that plantations producing staples for Europeans could bring fabulous wealth, the European powers grew less interested in the dwindling trade in precious metals and more eager to colonize. In the 1700s, large-scale planters of sugar, tobacco, and coffee began displacing small farmers who relied on one or two indentured servants (men and women who gained passage to the Americas in exchange for several years of work). Planters and their plantations won out because even cheaper slave labor allowed them to produce mass quantities of commodities at low prices.

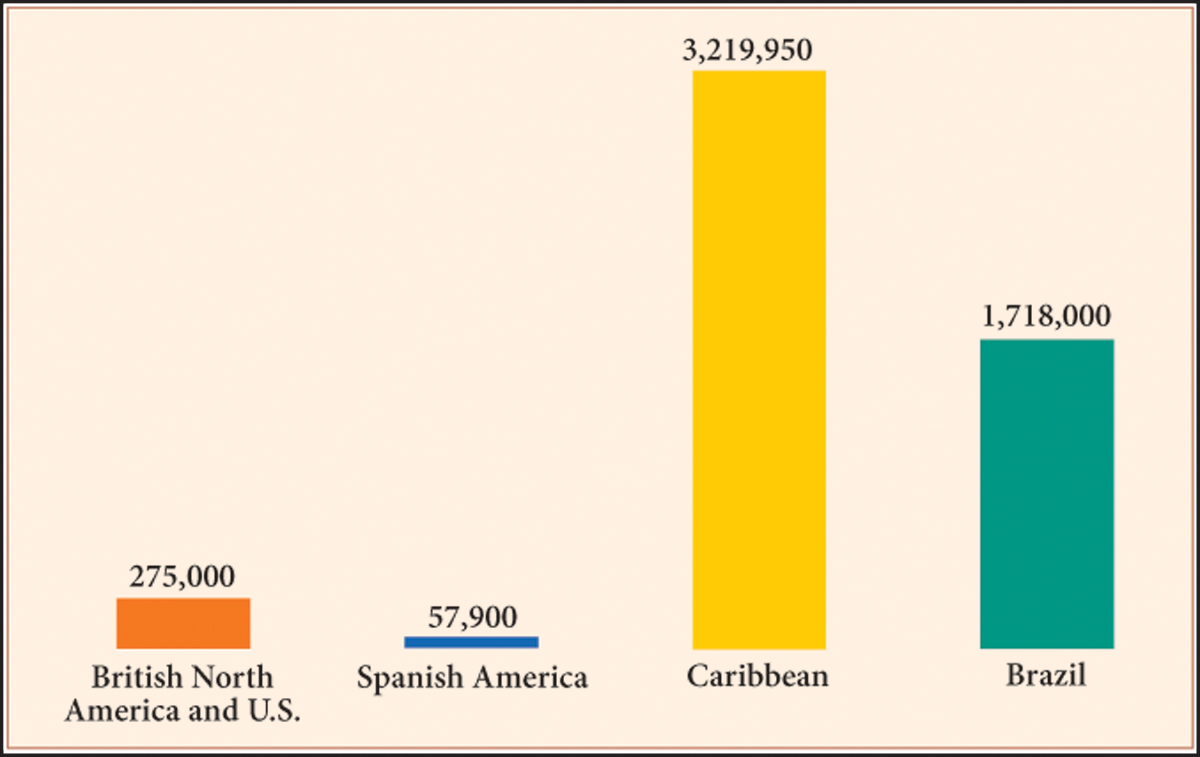

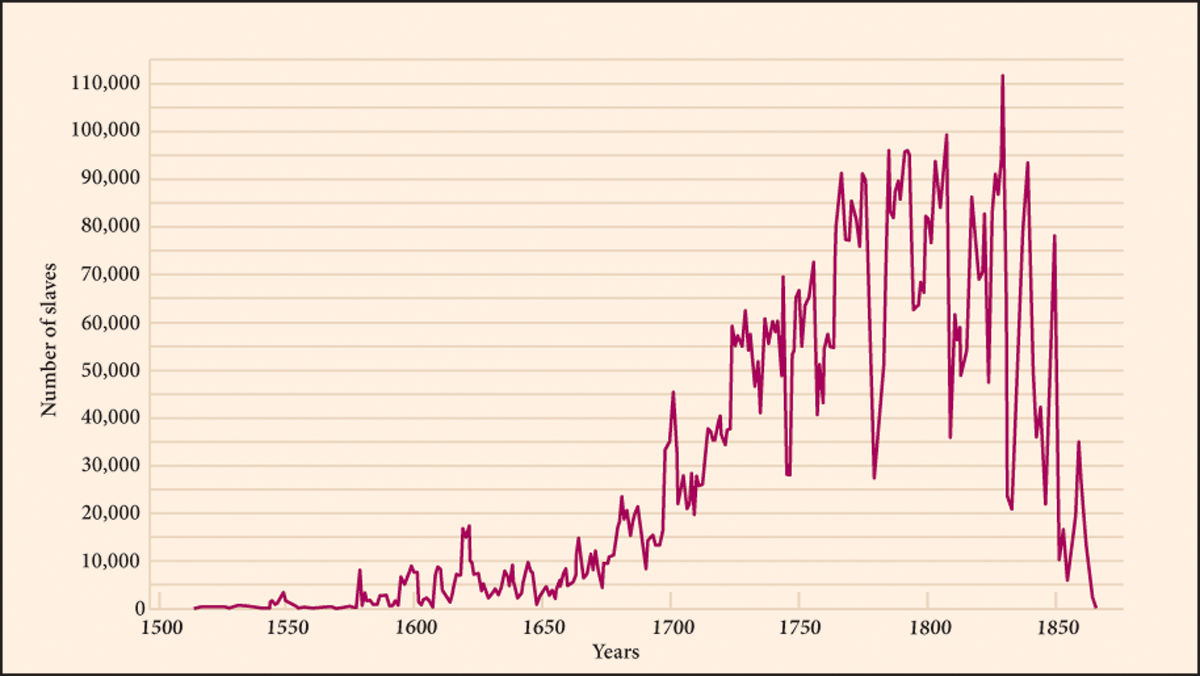

State-chartered private companies from Portugal, France, Britain, the Dutch Republic, Prussia, and even Denmark exploited the 3,500-mile coastline of West Africa for slaves. Before 1675, most blacks taken from Africa had been sent to Brazil or Spanish America on Portuguese or Dutch ships, but by 1725 more than 60 percent of African slaves landed in the Caribbean (Figure 17.1), and more and more of them were carried on British or French ships.

After 1700, the plantation economy also began to expand on the North American mainland. The numbers stagger the imagination (Figure 17.2). In all, more than ten million Africans, not counting those who were captured but died before or during the sea voyage, were transported to the Americas before 1850, after which the slave trade finally began to wind down. Europeans traded textiles, cowries (shells from the Indian Ocean), and firearms for slaves, altering local African power structures and creating political instability. Population declined in West Africa, and because two-thirds of those enslaved were men, husbands were in short supply and men increasingly took two or more wives in a practice known as polygyny.

The enslaved women and men suffered terribly. Most had been sold to European traders by Africans from the west coast who acquired them through warfare or kidnapping. The vast majority were between fourteen and thirty-five years old. Before cramming them onto the ships for the three-month trip, slavers shaved their heads and stripped them naked; they also branded some with red-hot irons. They separated men and women, and shackled men with leg irons. Sailors and officers raped the women at will. In the cramped and appalling conditions of the voyage, as many as one-fourth of the slaves died. (See “Seeing History: The ‘Invisibility’ of Slavery.”)

Those who survived the transit were sold and given new names, often only first names. Slaves had no social identities of their own; they were expected to learn their master’s language and to do any job assigned. Slaves worked fifteen- to seventeen-hour days and were fed only enough to keep them on their feet. The death rate among slaves was high, especially on the sugar plantations, where slaves had to cut and haul sugarcane to the grinders and boilers before it spoiled. During the harvest, grinding and boiling went on around the clock. Because so many slaves died in the sugar-growing regions, more and more slaves, especially strong males, had to be imported. In North America, in contrast, where sugar was a minor crop, the slave population increased tenfold by 1863 through natural growth.

Not surprisingly, despite the threat of torture or death on recapture, slaves sometimes ran away. Outright revolt was uncommon, but slaveholders’ fears about conspiracy and revolt lurked beneath the surface of every slave-based society. In 1710, the royal governor of Virginia reminded the colonial legislature of the need for unceasing vigilance: “We are not to Depend on Either Their Stupidity, or that Babel of Languages among ’em; freedom Wears a Cap which Can Without a Tongue, Call Togather all Those who Long to Shake off the fetters of Slavery.” Masters defended whipping and other forms of physical punishment as essential to maintaining discipline. Laws called for the castration of a slave who struck a white person.

The balance of white and black populations in the New World colonies varied greatly. Because they did not own plantations, New England merchants and farmers bought few slaves. Blacks—both slave and free—made up only 3 percent of the population in eighteenth-century New England, compared with 60 percent in South Carolina. The imbalance of whites and blacks was even more extreme in the Caribbean, where most indigenous people had already died fighting Europeans or the diseases brought by them. By 1713, the French Caribbean colony of St. Domingue (on the western part of Hispaniola, present-day Haiti) had four times as many black slaves as whites; by 1754, slaves there outnumbered whites more than ten to one.

Plantation owners often left their colonial possessions in the care of agents and merely collected the revenue so that they could live as wealthy landowners back home, where they built opulent mansions and gained influence in local and national politics. William Beckford, for example, left his inherited sugar plantations in Jamaica and moved the headquarters of the family business to London in the 1730s to be close to the government and financial markets. His holdings formed the single most powerful economic interest in Jamaica, but he preferred to live in England, where he held political office (he was lord mayor of London and a member of Parliament) and even loaned money to the government.

The slave trade permanently altered consumption patterns for ordinary people. Sugar had been prescribed as a medicine before the end of the sixteenth century, but the development of plantations in Brazil and the Caribbean made it a standard food item. By 1700, the British were sending home fifty million pounds of sugar a year, a figure that doubled by 1730. Equally pervasive was the spread of tobacco; by the 1720s, men of every country and class smoked pipes or took snuff.

Even though the traffic in slaves disturbed some Europeans, in the 1700s slaveholders began to justify their actions by demeaning the mental and spiritual qualities of the enslaved Africans. White Europeans and colonists sometimes described black slaves as animal-like, akin to apes. A leading New England Puritan asserted about the slaves: “Indeed their Stupidity is a Discouragement. It may seem, unto as little purpose, to Teach, as to wash an Aethiopian [Ethiopian].” One of the great paradoxes of this time was that talk of liberty and rights, especially prevalent in Britain and its North American colonies, coexisted with the belief that some people were meant to be slaves. The churches often defended or at least did not oppose the inequities of slavery.