The Limits of Reason: Roots of Romanticism and Religious Revival

Printed Page 584

Important EventsThe Limits of Reason: Roots of Romanticism and Religious Revival

In reaction to what some saw as the Enlightenment’s excessive reliance on the authority of human reason, a new artistic movement called romanticism took root. Although it would not fully flower until the early nineteenth century, romanticism traced its emphasis on individual genius, deep emotion, and the joys of nature to thinkers like Rousseau who had scolded the philosophes for ignoring those aspects of life that escaped and even conflicted with the power of reason.

A novel by the young German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) captured the early romantic spirit with its glorification of emotion. The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) told of a young man who loves nature and rural life and is unhappy in love. When the woman he loves marries someone else, he falls into deep melancholy and eventually kills himself. Reason cannot save him. The book spurred a veritable Werther craze: in addition to Werther costumes, engravings, embroidery, and medallions, there was even a perfume called Eau de Werther. The young Napoleon Bonaparte, who was to build an empire for France, claimed to have read Goethe’s novel seven times.

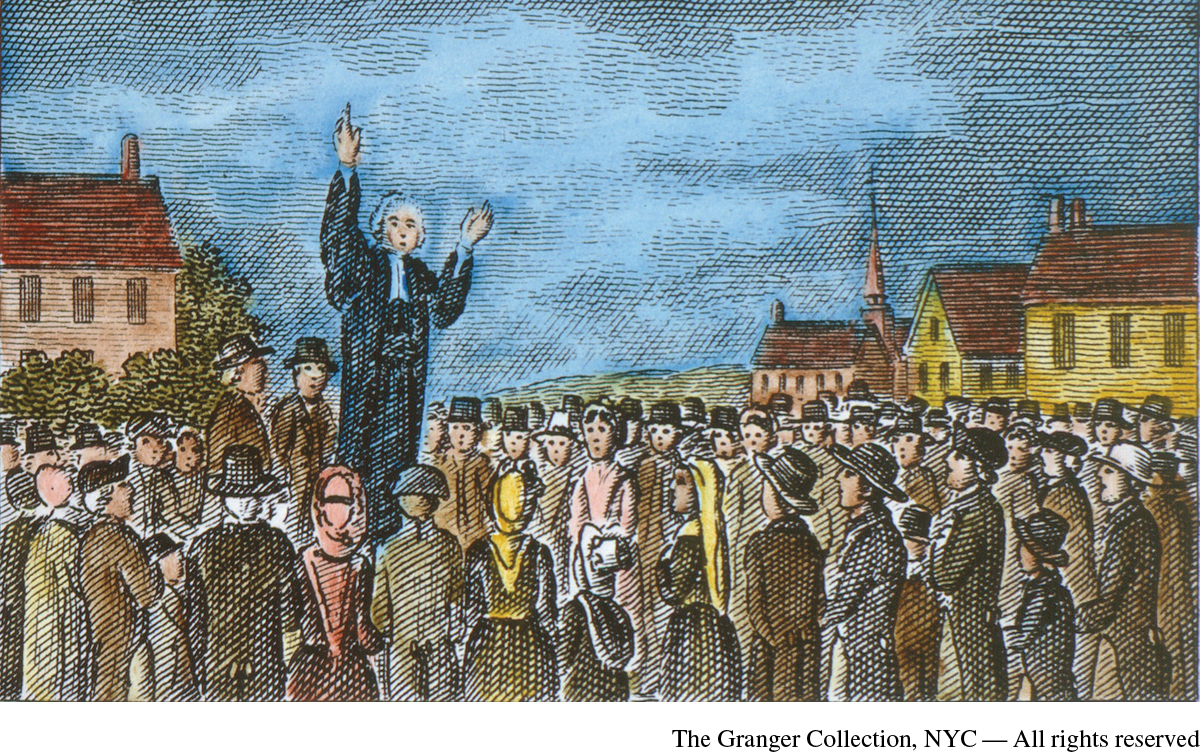

Religious revivals sought to underline the limits of reason by emphasizing a direct emotional connection with God. Much of the Protestant world experienced an “awakening” in the 1740s. In the German states, Pietist groups founded new communities; and in the British North American colonies, revivalist Protestant preachers drew thousands of fervent believers in a movement called the Great Awakening. In North America, bitter conflicts between revivalists and their opponents in the established churches prompted the leaders on both sides to set up new colleges to support their beliefs. These included Princeton, Columbia, Brown, and Dartmouth, all founded between 1746 and 1769 by either revivalists or antirevivalists.

Revivalism also stirred eastern European Jews at about the same time. Israel ben Eliezer (1698–1760) laid the foundation for Hasidism in the 1740s and 1750s. He traveled the Polish countryside offering miraculous cures and became known as the Ba’al Shem Tov (“Master of the Good Name”) because he used divine names to effect healing and bring believers into closer personal contact with God. He emphasized mystical contemplation of the divine, rather than study of Jewish law, and his followers, the Hasidim (Hebrew for “most pious” Jews), often expressed their devotion through music, dance, and fervent prayer. Their practices soon spread all over Poland-Lithuania.

REVIEW QUESTION What were the major differences between the Enlightenment in France, Great Britain, and the German states?

Most of the waves of Protestant revivalism ebbed after the 1750s, but in Great Britain one movement continued to grow through the end of the century. John Wesley (1703–1791), the Oxford-educated son of a cleric in the Church of England, founded Methodism, a term evoked by Wesley’s insistence on strict self-discipline and a methodical approach to religious study and observance. In 1738, Wesley began preaching his new brand of Protestantism, which emphasized an intense personal experience of salvation and a life of thrift, abstinence, and hard work. Traveling all over the British Isles, Wesley preached forty thousand sermons in fifty years, an average of fifteen a week. The Church of England refused to let him preach in the churches. In response, Wesley began to ordain his own clergy. While considered radical in religious views, the Methodist leadership remained politically conservative during Wesley’s lifetime; Wesley himself wrote many pamphlets urging order, loyalty, and submission to higher authorities.