The Revolution of Rights and Reason

Printed Page 614

Important EventsThe Revolution of Rights and Reason

Before drafting a constitution in 1789, the deputies of the National Assembly had to confront growing violence in the countryside. As food shortages spread, peasants feared that the beggars and vagrants crowding the roads might be part of an aristocratic plot to starve the French people by burning crops or barns. In many places, the Great Fear (the term used by historians to describe this rural panic) turned into peasant attacks on aristocrats or on the records of peasants’ seigneurial dues kept in lords’ castles.

Alarmed by peasant unrest, the National Assembly decided to make sweeping changes. On the night of August 4, 1789, noble deputies announced their willingness to give up their tax exemptions and seigneurial dues. The National Assembly decreed the abolition of what it called the feudal regime—that is, it freed the few remaining serfs and eliminated all special privileges in matters of taxation, including all seigneurial dues on land. (A few days later the deputies insisted on financial compensation for some of these dues, but most peasants refused to pay.) The Assembly also mandated equality of opportunity in access to government positions. Talent, rather than birth, was to be the key to success. Enlightenment principles were beginning to become law.

Three weeks later, the deputies drew up the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen as the preamble to a new constitution. In words reminiscent of the American Declaration of Independence, whose author, Thomas Jefferson, was in Paris at the time, it proclaimed, “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” The Declaration granted freedom of religion, freedom of the press, equality of taxation, and equality before the law. It established the principle of national sovereignty: the king derived his authority henceforth from the nation rather than from tradition or divine right.

By pronouncing all men free and equal, the Declaration immediately created new dilemmas. Did women have equal rights with men? What about free blacks in the colonies? How could slavery be justified if all men were born free? Did religious toleration of Protestants and Jews include equal political rights? Women never received the right to vote during the French Revolution, though Protestant and Jewish men did. (See “Document 19.1: The Rights of Minorities.”)

Some women did not accept their exclusion. In addition to joining demonstrations, such as the march to Versailles in October 1789 (see chapter opener), women wrote petitions, published tracts, and organized political clubs to demand more participation. In her Declaration of the Rights of Woman of 1791, writer and political activist Olympe de Gouges (1748–1793) played on the language of the official Declaration to make the point that women should also be included: “Woman is born free and lives equal to man in her rights.” De Gouges linked her complaints to a program of social reform in which women would have equal rights to property and public office and equal responsibilities in taxes and criminal punishment.

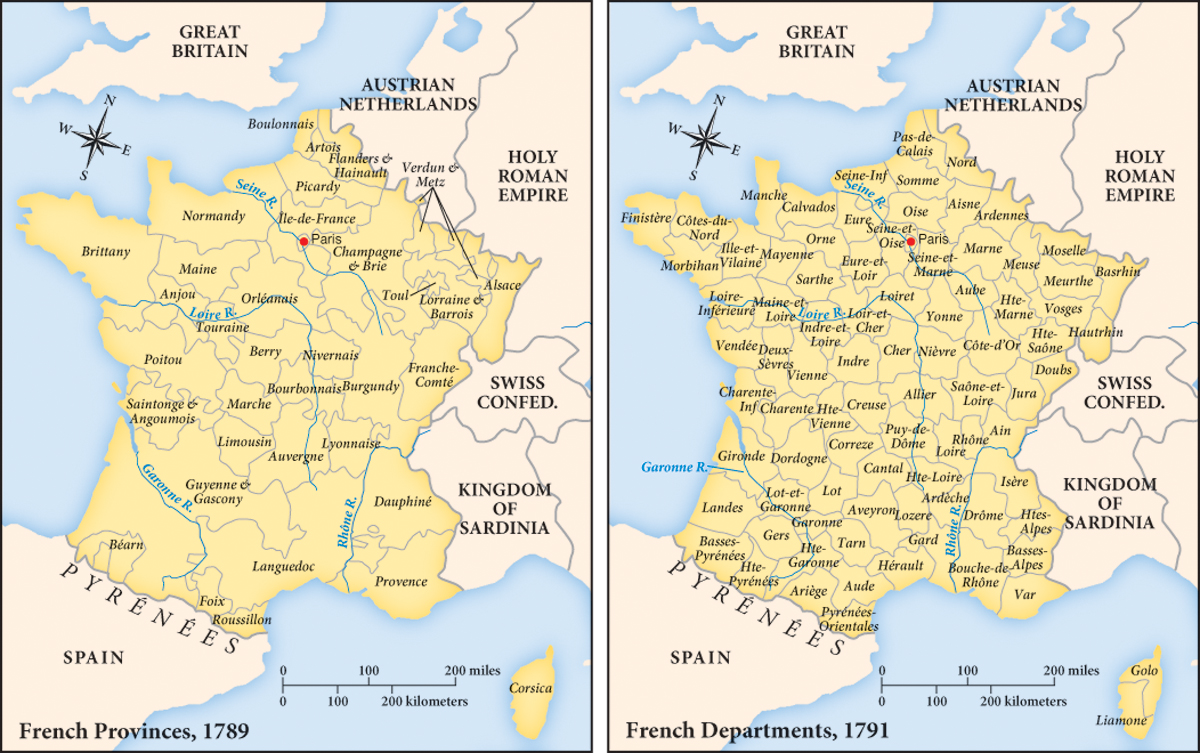

Unresponsive to calls for women’s equality, the National Assembly turned to preparing France’s first written constitution. The deputies gave voting rights only to white men who passed a test of wealth. Despite these limitations, France became a constitutional monarchy in which the king served as the leading state functionary. A one-house legislature was responsible for making laws. The king could postpone enactment of laws but not veto them. The deputies abolished all the old administrative divisions of the provinces and replaced them with a national system of eighty-three departments with identical administrative and legal structures (Map 19.1). All officials were elected; no offices could be bought or sold. The deputies also abolished the old taxes and replaced them with new ones that were supposed to be uniformly levied. The National Assembly had difficulty collecting taxes, however, because many people had expected a substantial cut in the tax rate. The new administrative system survived nonetheless, and the departments are still the basic units of the French state today.

When the deputies to the National Assembly turned to reforming the Catholic church, however, they created enduring conflicts. Convinced that monastic life encouraged idleness and a decline in the nation’s population, the deputies outlawed any future monastic vows and encouraged monks and nuns to return to private life by offering state pensions. Motivated partly by the ongoing financial crisis, the National Assembly confiscated all the church’s property and promised to pay clerical salaries in return. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy, passed in July 1790, provided that the voters elect their own parish priests and bishops just as they elected other officials. The impounded property served as a guarantee for the new paper money, called assignats, issued by the government. The assignats soon became subject to inflation because the government printed more and more money even as it sold the church lands to the highest bidders in state auctions.

Faced with resistance to these changes, the National Assembly in November 1790 required all clergy to swear an oath of loyalty to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Pope Pius VI in Rome condemned the constitution, and half of the French clergy refused to take the oath. The oath of allegiance permanently divided the Catholic population. The revolutionary government lost many supporters by passing laws against the clergy who refused the oath and by sending them into exile, deporting them forcibly, or executing them as traitors.