Cultural Responses to the Social Question

Printed Page 683

Important EventsCultural Responses to the Social Question

The social question, an expression reflecting the widely shared concern about social changes arising from industrialization and urbanization, pervaded all forms of art and literature. The dominant artistic movement of the time, romanticism, generally took a dim view of industrialization. The English-born American painter Thomas Cole (1801–1848) complained in 1836: “In this age . . . a meager utilitarianism seems ready to absorb every feeling and sentiment, and what is sometimes called improvement in its march makes us fear that the bright and tender flowers of the imagination shall all be crushed beneath its iron tramp.” Yet culture itself underwent important changes as the growing capitals of Europe attracted flocks of aspiring painters and playwrights; the 1830s and 1840s witnessed an explosion in culture as the number of would-be artists increased dramatically and new technologies such as photography and lithography brought art to the masses. Many of these new intellectuals would support the revolutions of 1848.

Because romanticism tended to glorify nature and reject industrial and urban growth, romantics often gave vivid expression to the problems created by rapid economic and social transformation. The English poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, best known for her love poems, denounced child labor in “The Cry of the Children” (1843). In Rain, Steam, and Speed: The Great Western Railway (1844), the leading English romantic painter, Joseph M. W. Turner (1775–1851), portrayed the struggle between the forces of nature and the means of economic growth. Turner was fascinated by steamboats: in The Fighting “Téméraire” Tugged to Her Last Berth to Be Broken Up (1838), he featured the victory of steam power over more conventional sailing ships.

Increased literacy, the spread of reading rooms and lending libraries, and serialization in newspapers and journals gave novels a large reading public. Unlike the fiction of the eighteenth century, which had focused on individual personalities, the great novels of the 1830s and 1840s specialized in the portrayal of social life in all its varieties. Manufacturers, financiers, starving students, workers, bureaucrats, prostitutes, underworld figures, thieves, and aristocratic men and women filled the pages of works by popular writers. Hoping to get out of debt, the French writer Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850) pushed himself to exhaustion and a premature death by cranking out ninety-five novels and many short stories. He aimed to catalog the social types that could be found in French society. Many of his characters, like himself, were driven by the desire to climb higher in the social order.

The English fiction writer Charles Dickens (1812–1870) worked with a similar frenetic energy and for much the same reason. When his father was imprisoned for debt in 1824, the young Dickens took a job in a shoe-polish factory. He eventually became a journalist and managed to produce a series of novels that attracted thousands of readers. In them, he paid close attention to the distressing effects of industrialization and urbanization. In The Old Curiosity Shop (1841), for example, he depicts the Black Country, the manufacturing region west and northwest of Birmingham, as a “cheerless region,” a “mournful place,” in which tall chimneys “made foul the melancholy air.”

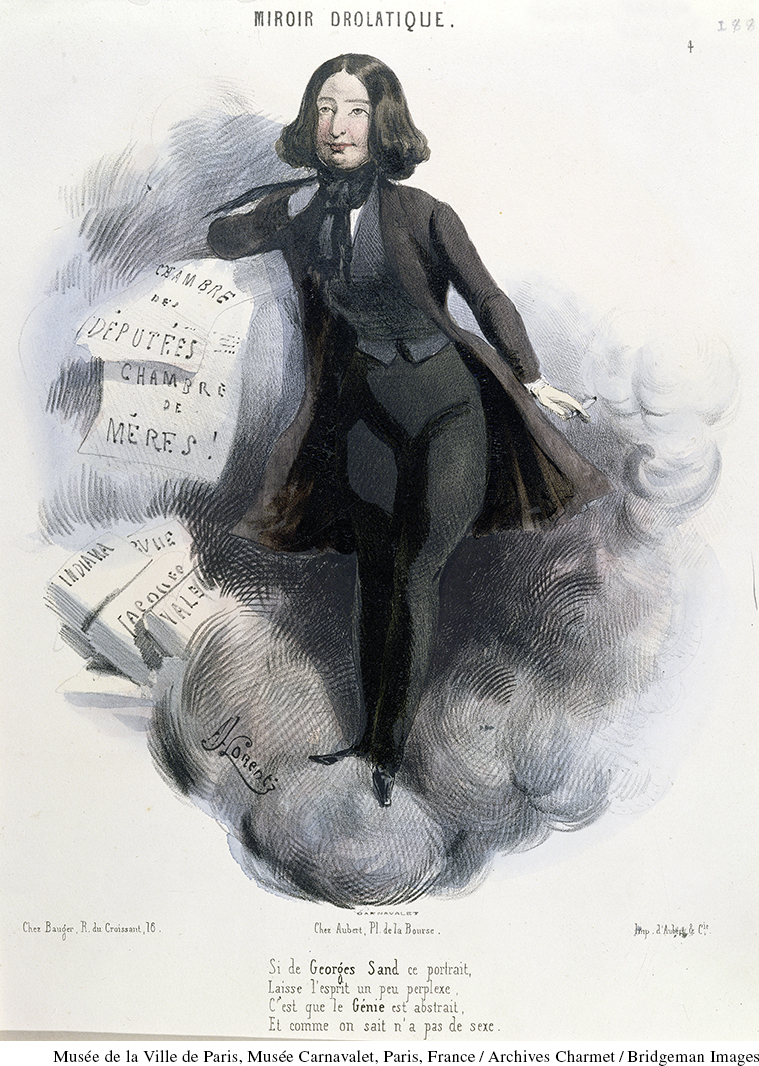

Novels by women often revealed the bleaker side of women’s situations. Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) describes the difficult life of an orphaned girl who becomes a governess, the only occupation open to most single middle-class women. The French novelist Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin Dudevant (1804–1876), writing under the pen name George Sand, took her social criticism a step further. She announced her independence in the 1830s by dressing like a man and smoking cigars. Though she published her work under a male pseudonym, as did many other women writers of the time, she created female characters who prevail in difficult circumstances through romantic love and moral idealism. Her notoriety—she became the lover of the Polish pianist and composer Frédéric Chopin, among others, and threw herself into socialist politics—made the term George-Sandism a common expression of disdain toward independent women.

As artists became more interested in society and social relations, ordinary citizens crowded cultural events. Museums opened to the public across Europe. Popular theaters in big cities drew thousands from the lower and middle classes every night; in London, for example, some twenty-four thousand people attended eighty “penny theaters” nightly. The audience for print culture also multiplied. In the German states, for example, the production of new literary works doubled between 1830 and 1843, as did the number of periodicals and newspapers and the number of booksellers. Young children and ragpickers sold cheap prints and books door-to-door or in taverns.

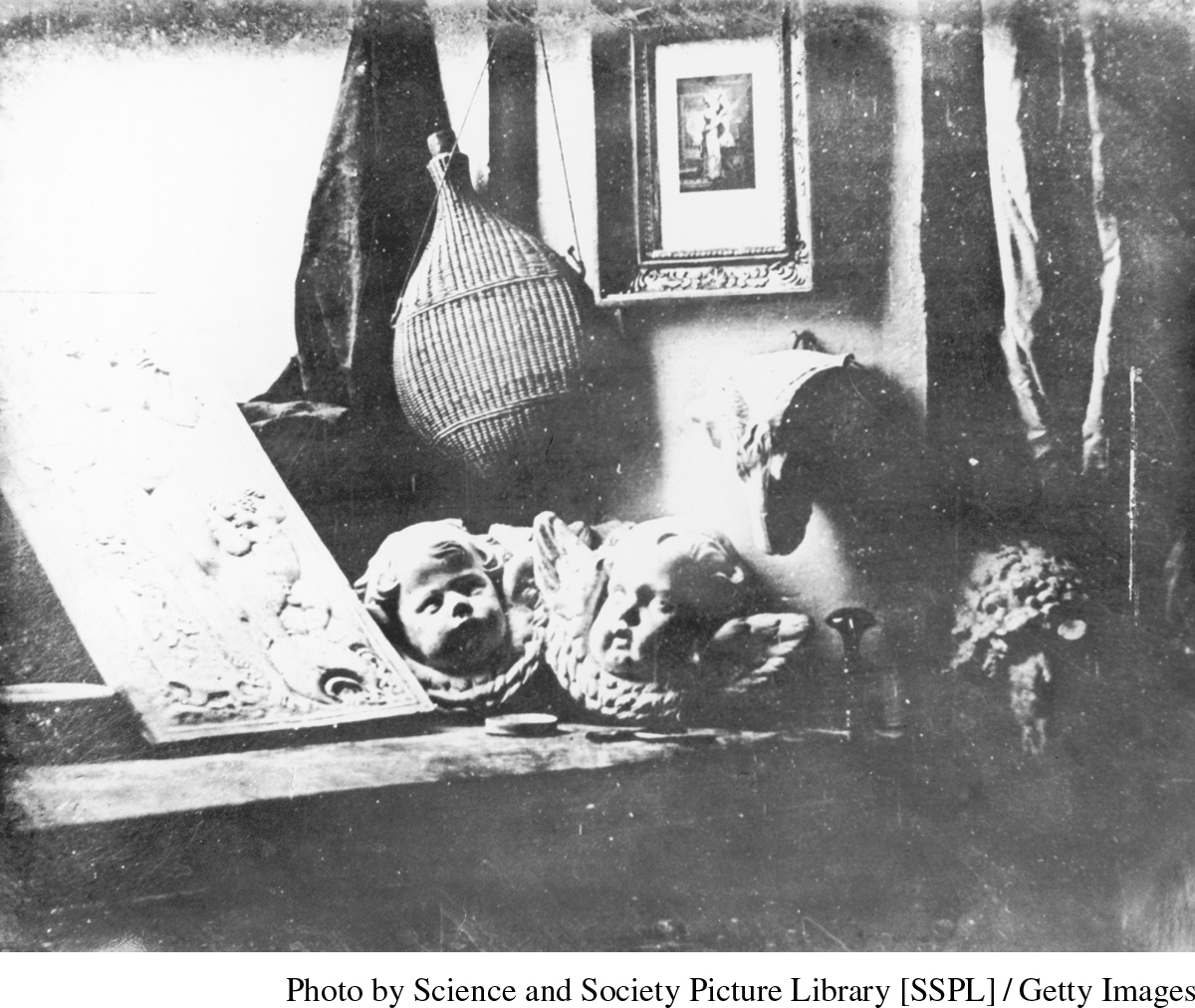

The advent of photography in 1839 provided an amazing new medium for artists. The daguerreotype, named after its inventor, French painter Jacques Daguerre (1787–1851), prompted one artist to claim that “from today, painting is dead.” Although this prediction was highly exaggerated, photography did open up new ways of portraying reality. It did so only gradually, however, as early photographs required exposure times of twenty to thirty minutes, making it impossible to capture anything or anyone in movement.

Culture expanded its reach in part because the ranks of artists and writers swelled. Estimates suggest that the number of painters and sculptors in France, the undisputed center of European art at the time, grew sixfold between 1789 and 1838. Not everyone could succeed in this hothouse atmosphere, in which writers and artists furiously competed for public attention. Their own troubles made some of them more keenly aware of the hardships faced by the poor. A satirical article in one of the many bitingly critical journals and booklets published in Berlin proclaimed: “In Ipswich in England a mechanical genius has invented a stomach, whose extraordinary efficient construction is remarkable. This artificial stomach is intended for factory workers there and is adjusted so that it is fully satisfied with three lentils or peas; one potato is enough for an entire week.”