Introduction for Chapter 22

Printed Page 708

Important Events

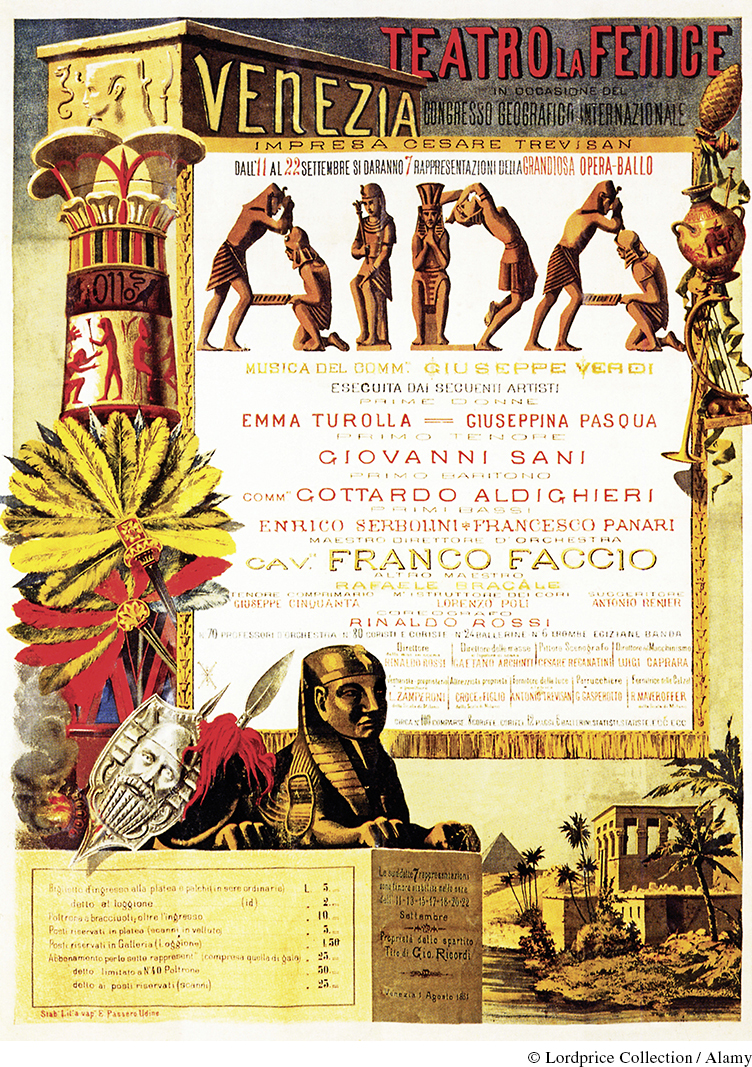

IN 1859, THE NAME VERDI suddenly appeared scrawled on walls across the cities of the Italian peninsula. The graffiti seemed to celebrate the composer Giuseppe Verdi, whose operas thrilled crowds of Europeans. Among Italians, Verdi was a particular hero; his stories of downtrodden groups struggling against tyrannical government seemed to refer specifically to them. As his operatic choruses thundered out calls to rebellion in the name of the nation, Italian audiences were sure that Verdi was telling them to throw off Austrian and papal rule and unite in a newborn Roman Empire. VERDI also formed an acronym for Vittorio Emmanuele Re d’Italia (“Victor Emmanuel, King of Italy”), and in 1859 it summoned Italians to unite under Victor Emmanuel II, king of Sardinia and Piedmont—the one Italian leader with a nationalist, modernizing profile. The graffiti was good publicity, for the very next year Italy united as a result of warfare and hard bargaining by political realists.

After the failed revolutions of 1848, European statesmen and the politically aware public increasingly rejected idealism in favor of Realpolitik—a politics of tough-minded realism aimed at strengthening the state and tightening social order. Realpolitikers disliked the romanticism of the revolutionaries. Instead, they put their faith in power politics and even the use of violence to attain their goals. Two particularly skilled practitioners of Realpolitik, the Italian Camillo di Cavour and the Prussian Otto von Bismarck, succeeded in unifying Italy and Germany not by romantic slogans but by war and diplomacy. Most leading figures of the 1850s and 1860s, enmeshed like Verdi’s operatic heroes in power politics, strengthened their states by harnessing the forces of nationalism and liberalism that had led to earlier romantic revolts. Their achievements changed the face of Europe.

Making a modern nation-state was a complicated task. Economic development was also crucial, as was using government policy and culture to create a sense of national identity and common purpose. Governments took vigorous steps to improve rapidly growing cities, promote public health, and boost national loyalty. State institutions such as public schools helped establish a common fund of knowledge and political beliefs. Authoritarian leaders like Bismarck and the new French emperor Napoleon III believed that a better quality of life would not only make the state more stable by calming revolutionary impulses of years past but also silence liberal critics.

Culture built a sense of belonging. Reading novels, attending operas and art exhibitions, and visiting the newly fashionable world’s fairs gave ordinary people a stronger sense of being French or German or British. Like politicians, artists and writers also came to reject romanticism, featuring instead harsher, more realistic aspects of everyday life. Artists painted nudes in shockingly blunt ways, eliminating romantic hues and dreamy poses. Authors wrote about the bleak life of soldiers in wartime or about ordinary people suffering poverty or turning to crime. Alongside the tough-minded nation-building policies there arose tough-minded art, not just mirroring Realpolitik but encouraging it.

CHAPTER FOCUS How did political, international, societal, and cultural developments in individual countries and across Europe in the mid-nineteenth century help create and strengthen nation states?

In their quest to build strong nations, Western politicians did not shy away from using violence or causing harm. They sent armies to distant areas to stamp out resistance to their continuing global expansion. At home, governments uprooted neighborhoods to construct public buildings, roads, and parks. The process of nation building was often brutal, bringing foreign wars, arrests, and even civil war—all the centerpieces of many Verdi operas. In 1871, an uprising of Parisians challenged the central government’s intrusion into everyday life and its failure to count the costs. Thus, for the most part, the powerful Western nation-state did not arise spontaneously. Instead, its growth and the tighter unification of peoples depended on shrewd policy, deliberate warfare, and new inroads into societies around the world—which together formed the basis of Realpolitik.