The Crimean War, 1853–1856: Turning Point in European Affairs

Printed Page 712

Important EventsThe Crimean War, 1853–1856: Turning Point in European Affairs

Napoleon III first flexed his diplomatic muscle in the Crimean War (1853–1856), which began as a conflict between the Russian and Ottoman Empires but ended as a war with long-lasting consequences for much of Europe. While professing to uphold the status quo, Russia had been expanding into Asia and the Middle East. In particular, Tsar Nicholas I wanted territory in the Ottoman Empire, and Napoleon encouraged Nicholas to be even more aggressive in his expansionism—a maneuver that provoked war in October 1853 between the two eastern empires (Map 22.1).

The war drew in other states and upset Europe’s balance of power as set in the Congress of Vienna. Napoleon III convinced Austria to remain neutral during the war, thus splitting the conservative Russian-Austrian coalition that had checked French ambitions since 1815. The Austrian government was concerned that the defeat of the Ottomans would bring Russian expansion into the Balkans. To protect its Mediterranean routes to East Asia, Britain prodded the Ottomans to stand up to Russia, but in the fall of 1853, the Russians blasted the Turkish wooden ships to bits at the Ottoman port of Sinope on the Black Sea. The Russians justified their actions as a necessary defense of Christians in the Ottoman Empire. In 1854, France and Great Britain, though enemies in war for more than a century, allied to declare war on Russia and defend the Ottoman Empire.

The Crimean War was spectacularly bloody. British and French troops landed in the Crimea in September 1854 and waged a long siege of the Russian naval base at Sevastopol, which fell only after a year of savage and costly combat. Generals on both sides demonstrated their incompetence, and governments failed to provide combatants with even minimal supplies, sanitation, or medical care. Hospitals had no beds, no dishes, and no water. A million men died, more than two-thirds from disease or starvation.

In the midst of this unfolding catastrophe, Alexander II (r. 1855–1881) ascended the Russian throne after the death of Nicholas I, his father. With casualties mounting, the new tsar asked for peace. As a result of the Peace of Paris, signed in March 1856, Russia lost the right to base its navy in the Strait of Dardanelles and the Black Sea, which were declared neutral waters. Moldavia and Wallachia (which soon merged to form Romania) became autonomous Turkish provinces under the victors’ protection, drastically reducing Russian influence in that region, too.

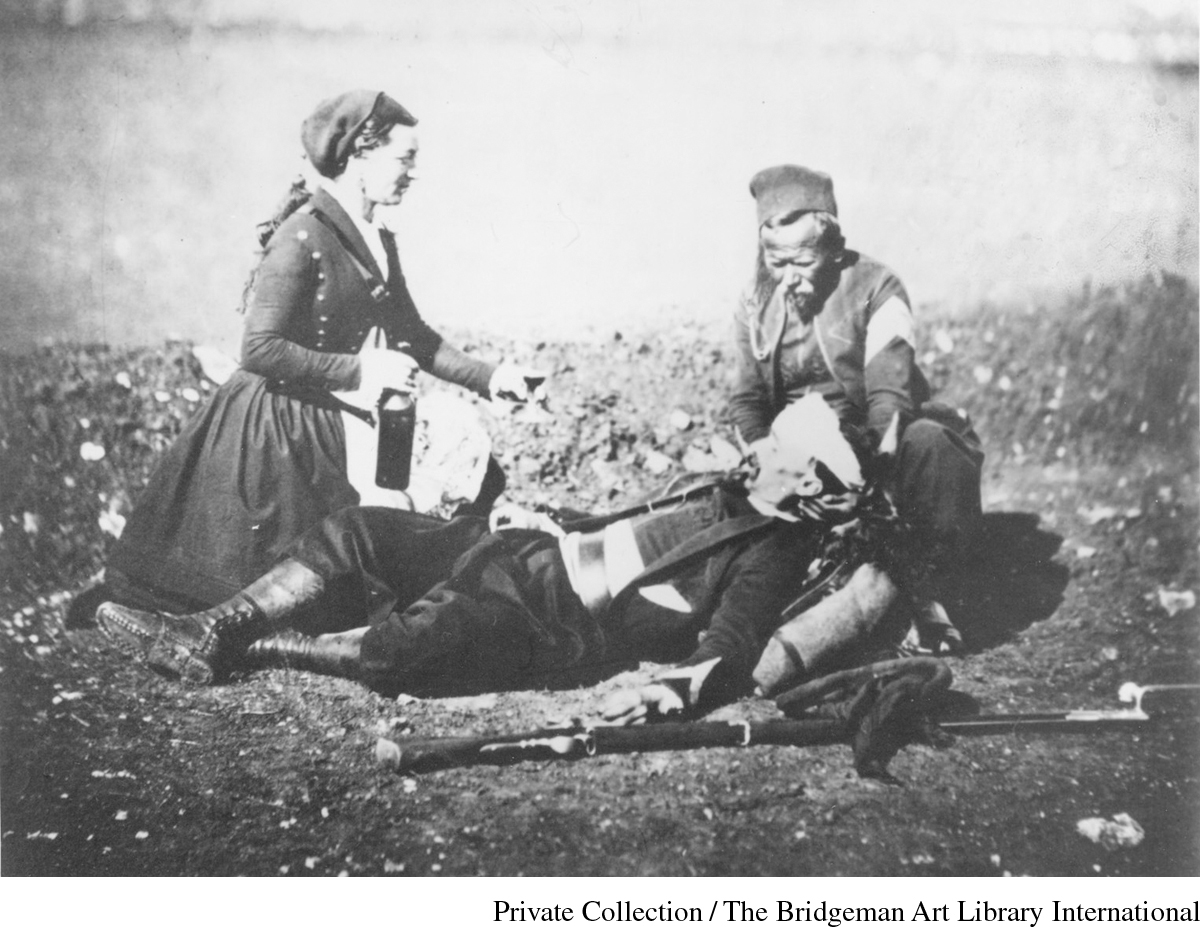

The Crimean War was full of consequence. New technologies were introduced into warfare: the railroad, shell-firing cannons, breech-loading rifles, and steam-powered ships. The telegraph and increased press coverage brought news from the Crimean front lines to home audiences more rapidly and in more detail than ever before. Reports of incompetent leadership, poor sanitation, and the huge death toll outraged the public, inspiring some civilians, such as the British nurse Florence Nightingale, to head for the front lines to help. Nightingale seized the moment to escape the confines of middle-class domesticity by organizing a battlefield nursing service to care for the British sick and wounded. Through her tough-minded organization of nursing units, she pioneered nursing as a profession and made sanitary conditions for soldiers a new and permanent priority. (See “Document 22.1: Mrs. Seacole: The Other Florence Nightingale.”)

More immediately, the war accomplished Napoleon III’s goal of severing the alliance between Austria and Russia, the two conservative powers on which the Congress of Vienna peace settlement had rested since 1815. It thus ended Austria’s and Russia’s grip on European affairs and undermined their ability to contain the forces of liberalism and nationalism.