Reform in Russia

Printed Page 713

Important EventsReform in Russia

Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War also made clear the need for meaningful reform. Hundreds of peasant insurrections had erupted in the decade before the war. “Our own and neighboring households were gripped with fear,” one aristocrat reported. The Russian economy stagnated compared with that of western Europe. Old-fashioned farming techniques depleted soil and led to food shortages, and the nobility often ignored the suffering caused by malnutrition and hard labor. When Russia lost the Crimean War, the educated public, including some government officials, found the poor performance of serf armies a disgrace and the system of serf labor a glaring weakness.

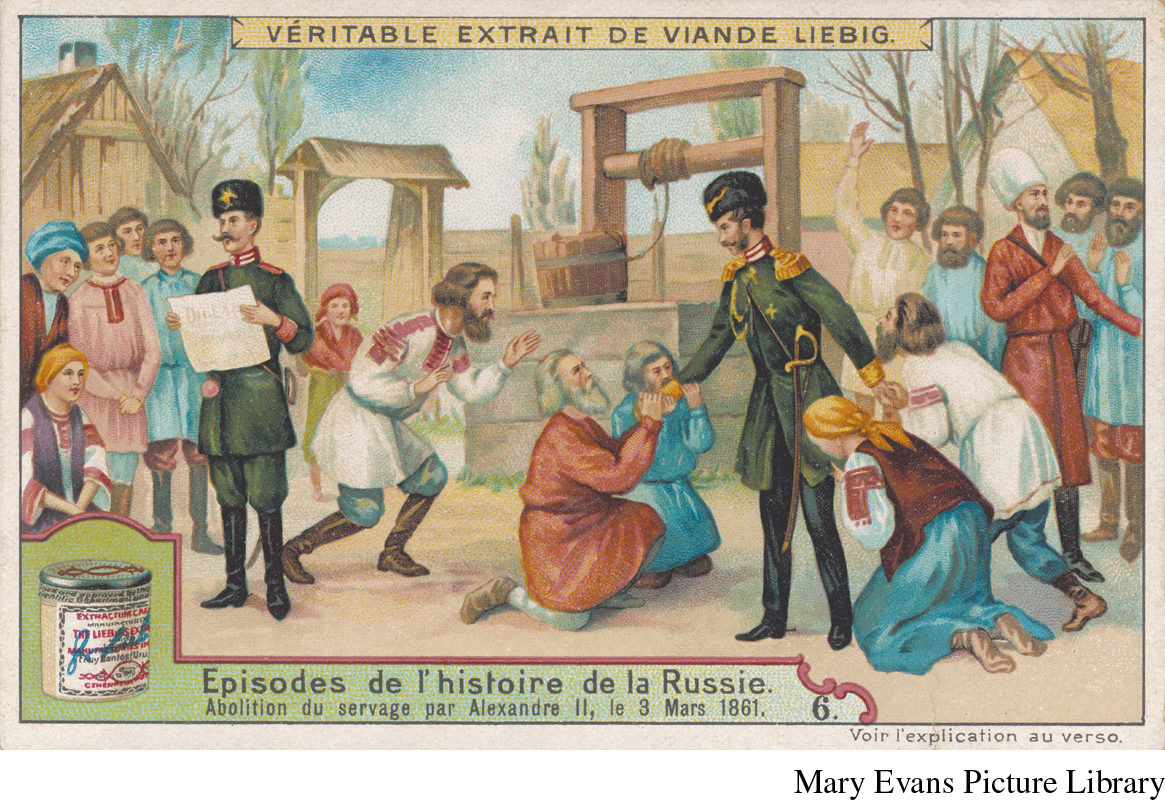

Confronted with the need for change, Tsar Alexander II acted. Well educated and more widely traveled than his father, Alexander ushered in what came to be known as the Great Reforms. These granted Russians new rights from above as a way of preventing violent action from below. The most dramatic reform was the emancipation of almost fifty million serfs beginning in 1861. By the terms of emancipation, communities of newly freed serfs, headed by male village elders, received grants of land. The community itself, traditionally called a mir, had full power to allocate this land among individuals and to direct their economic activity. Communal landowning and decision making meant that individual peasants could not simply sell their parcel of land and leave their rural communities to work in factories, as laborers had been doing elsewhere in Europe.

In Russia peasants were not given land along with their personal freedom: they were forced to “redeem” the land they farmed by paying off long-term loans from the government, which in turn compensated the original landowners. The best land remained in the hands of the nobility, and the huge burden of debt and communal regulations slowed Russian agricultural development for decades. Even so, idealistic reformers believed that the emancipation of the serfs, once treated by the nobility virtually as livestock, had produced miraculous results. As one of them put it, “The people are without any exaggeration transfigured from head to foot. . . . The look, the walk, the speech, everything is changed.”

The Russian state also reformed local administration, the judiciary, and the military. The government set up zemstvos—regional councils—through which aristocrats could control local affairs such as education, public health, and welfare. Zemstvos became a new political force with the potential for challenging the authoritarian central government. Some aristocrats took advantage of newly relaxed rules on travel to see how the rest of Europe was governed. Their vision broadened as they observed different ways of solving social and economic problems. The principle of equality of all persons before the law, regardless of social rank, was introduced in Russia for the first time as judicial reform gave all Russians access to modern civil courts. Military reform followed in 1874 when the government reduced the twenty-five-year period of service to a six-year term and began focusing on educating troops in an effort to match the efficiency and fitness of soldiers in western Europe.

Alexander’s reforms helped landowners be more effective in the market even as they reduced the privileges of the nobility, weakening their authority and sparking family conflict. “An epidemic seemed to seize upon [noble] children . . . an epidemic of fleeing from the parental roof,” one observer noted. Rejecting aristocratic leisure, youthful rebels from the upper class valued practical activity and sometimes identified with peasants and workers instead of their own class. Some formed communes in which they hoped to do humble manual labor; others turned to higher education, especially the sciences. Daughters of the nobility opposed their parents, escaping from home through phony marriages so they could study in western European universities. (See “Document 22.2: Education of a Mathematical Genius in Russia.”) This rejection of traditional society led some to label these young people as nihilists (from the Latin for “nothing”)—implying a lack of belief in any values whatsoever. In fact, however, the so-called nihilists represented a defiant spirit percolating not just at the bottom but also at the top of Russian society.

REVIEW QUESTION What were the main results of the Crimean War?

The atmosphere of change also inspired resistance among the more than one hundred Russian-dominated ethnic groups in the Russian Empire. Aristocratic and upper-class nationalist Poles staged an uprising in 1863, demanding full national independence for their country. By 1864, however, Alexander II’s army had crushed them. The government then swiftly clamped down on other nationalist uprisings and enforced Russification—a tactic meant to reduce the threat of future rebellion by insisting that ethnic minorities within the empire adopt Russian language and culture. Despite these measures, the tsarist regime only partially succeeded in developing the administrative, economic, and civic institutions that made the nation-state strong elsewhere in Europe, allowing few to share in power. In imperial Russia, autocracy and continued abuse of many in the population slowed the development of the sense of common citizenship forming elsewhere in the West, while the urge to revolt grew.