Introduction for Chapter 24

Printed Page 782

Important Events

IN THE FIRST DECADE of the twentieth century, a wealthy young Russian man traveled from one country to another to find relief from a common malady of the time called neurasthenia. Its symptoms included fatigue, lack of interest in life, depression, and sometimes physical illness. In 1910, the young man consulted Sigmund Freud, a Viennese physician whose unconventional treatment—eventually called psychoanalysis—took the form of a conversation about the patient’s dreams, sexual experiences, and everyday life. Over the course of four years, Freud uncovered his patient’s deeply hidden fear of castration, which was disguised as a fear of wolves—thus the name Wolf-Man, by which he is known to us. Freud worked his cure, as the Wolf-Man himself put it, “by bringing repressed ideas into consciousness” through extensive talking.

In many ways, the Wolf-Man could be said to represent his time. Born into a family that owned vast estates, he reflected Europe’s growing prosperity, though on a grander scale than most. Countless individuals were troubled, even mentally disturbed like the Wolf-Man, and suicides were not uncommon. The Wolf-Man’s own sister and father died from intentional drug overdoses. As the twentieth century opened, Europeans raised questions about family, gender relationships, empire, religion, and the consequences of technology. Every sign of imperial wealth brought on an apparently irrational sense of Europe’s decline. British writer H. G. Wells saw in this prosperous era “the sunset of mankind.” Gloom filled the pages of many a book and upset the lives of individuals like the Wolf-Man.

Conflict rattled the world as a growing number of powers, including Japan and the United States, fought their way into even more territories. The nations of Europe had lurched from one diplomatic crisis to another over access to global resources and control of territory—both within Europe and outside it. Competition for empire fueled an arms race that threatened to turn Europe—the most civilized region of the world, according to its leaders—into a savage battleground. In domestic politics, militant nationalism stirred ethnic hatreds and furthered anti-Semitic violence. Women suffragists along with other politically disadvantaged groups such as the Slavs and Irish demanded full citizenship, even as political assassinations and public brutality swept away the liberal values of tolerance and human rights.

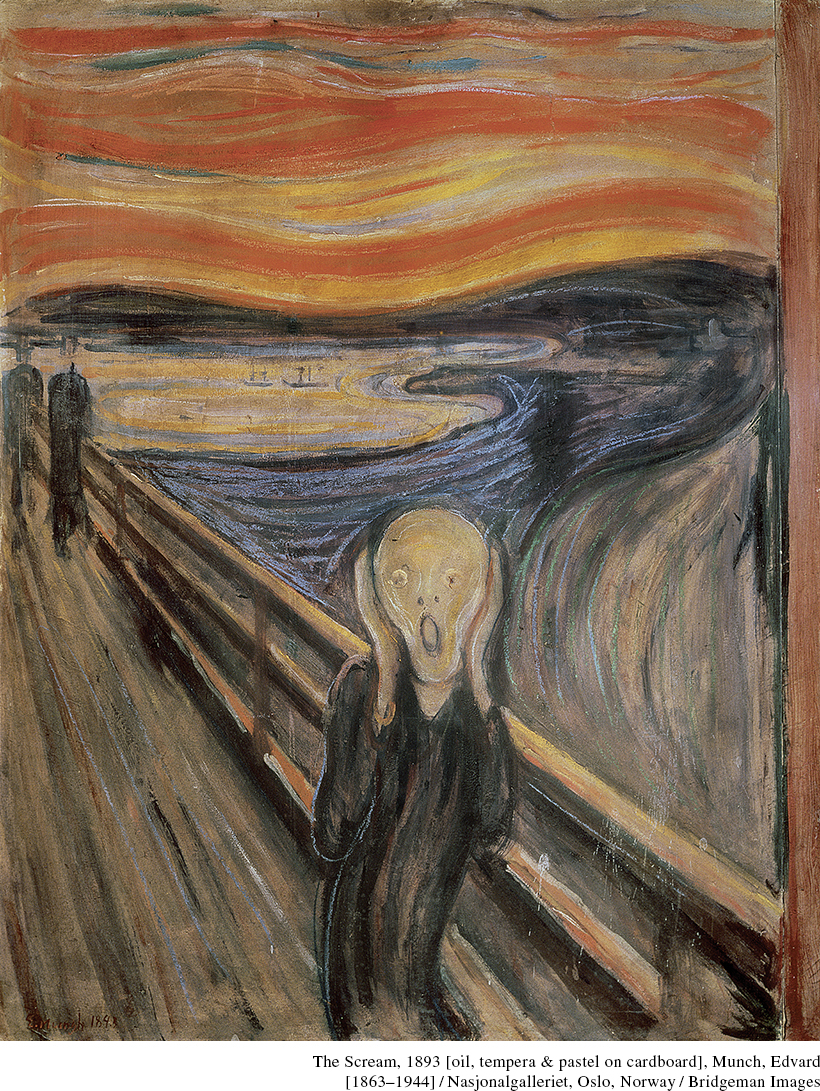

These were just some of the conflicts associated with the term modernity, often used to describe the rise of mass politics, the spread of technology, and the faster pace of life—all of which were visible in the West from the late nineteenth century on. (See “Terms of History: Modern.”) The word modern was also applied to art, music, science, and philosophy of this period. Although many people today admire the brilliant, innovative qualities of modern art, music, and dance, people of the time were offended, even outraged, by the new styles and sounds. Freud’s theory that sexual drives exist in even the youngest children shocked people. Every advance in science and the arts simultaneously undermined middle-class faith in the stability of Western civilization.

CHAPTER FOCUS How did developments in social life, art, intellectual life, and politics at the turn of the twentieth century produce instability and set the backdrop for war?

That faith was further tested when the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne was assassinated in June 1914. Few gave much thought to the global significance of the event, least of all the Wolf-Man, whose treatment with Freud was just ending. He viewed the fateful day of June 28 simply as the day he “could now leave Vienna a healthy man.” Yet the assassination put the spark to the powder keg of international discord that had been building for several decades. The resulting disastrous war, World War I, like the insights of Freud, would transform life in the West.