The Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939

Printed Page 877

Important EventsThe Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939

Spain seemed to be headed toward democracy when, in 1931, Spanish republicans overthrew the monarchy and the dictatorship that ruled in its name. For centuries, the Spanish state had backed the domination of large landowners and the Catholic clergy in the countryside. These ruling elites kept an impoverished peasantry in their grip, making Spain a country of economic extremes. People in industrial cities reacted enthusiastically to the end of the dictatorship and began debating the course of change, with constitutionalists, anarchists, Communists, and other splinter groups disagreeing on how to create a democratic nation. For republicans, the air was electric with promise. As one woman recalled: “We saw a backward country suddenly blossoming out into a modern state. We saw peasants living like decent human beings. We saw men allowed freedom of conscience.”

With little political experience, however, the republic had a hard time putting in place a political program that would gain support in the countryside. Instead of building popular loyalty by enacting land reform, the various antimonarchist factions struggled among themselves to shape the new government. They wanted political and economic modernization, but they failed to mount a unified effort against their reactionary opponents. In 1936, growing monarchist opposition frightened the pro-republican forces into forming a Popular Front coalition to win elections and prevent the republic from collapsing.

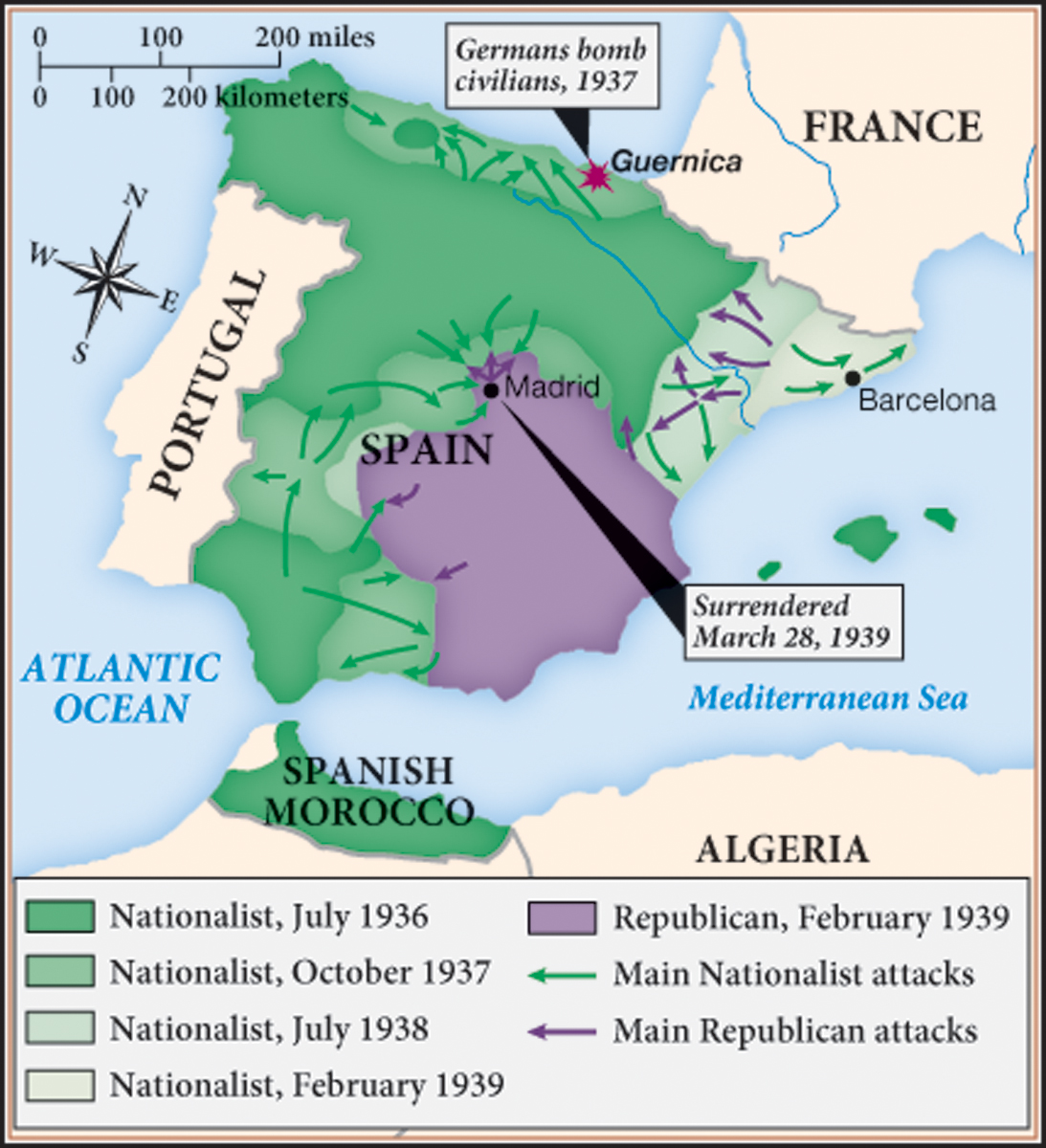

In response to the Popular Front victory, a group of army officers led by General Francisco Franco (1892–1975) staged an uprising against the republic in 1936. The rebels, who included monarchist landowners, the clergy, and the fascist Falange Party, soon had the help of fascists in other parts of Europe. Pro-republican citizens—male and female—fought back by forming armed volunteer units. In their minds, citizen armies symbolized republicanism, while professional troops followed the aristocratic rebels against democracy. As civil war gripped the country, the republicans generally held Madrid, Barcelona, and other commercial and industrial areas. The right-wing rebels took the agricultural west and south (Map 26.1).

Spain became a training ground for World War II. Hitler and Mussolini sent military personnel in support of Franco, gaining the opportunity to practice the terror bombing of civilians. In 1937, German planes attacked the town of Guernica, mowing down civilians in the streets. This useless slaughter inspired Pablo Picasso’s memorial mural to the dead, Guernica (1937), in which the intense suffering is starkly displayed. The Spanish republic appealed everywhere for assistance, but only the Soviet Union answered. Britain and France refused to provide aid despite the outpouring of popular support for the cause of democracy. Instead, a few thousand volunteers from a variety of countries—including many students, journalists, and artists—fought for the republic. “Spain was the place to stop fascism,” these volunteers believed. The aid Franco received helped his professional armies defeat the republicans in 1939, strengthening the cause of military authoritarianism in Europe. Tens of thousands fled Franco’s brutal revenge; remaining critics found themselves jailed or worse.