The War against Civilians

Printed Page 883

Important EventsThe War against Civilians

Far more civilians than soldiers died in World War II. The Axis powers and Allies alike bombed cities to destroy civilian will to resist: the Allied firebombings of Dresden and Tokyo killed tens of thousands of civilians, though Axis attacks were more widespread. The British people, not British soldiers, were the target of the battle of Britain, and in Poland and Ukraine, the Nazi SS murdered hundreds of thousands of Polish citizens. Confiscated Polish land and homes were given to “racially pure” Aryans from Germany and other central European countries. In the name of collectivization, Soviet forces perpetuated the same violence in the same area of eastern Europe, which has been called the “Bloodlands” for the millions who died in the battle for land and food.

Nazi and Soviet leaders saw literate people in the conquered areas as leading members of the civil society that they wanted to destroy. A ploy of the Nazis was to test captured people’s reading skills, suggesting that those who could read would be given clerical jobs while those who could not would be relegated to hard labor. Those who could read, however, were lined up and shot. Because many in the German army initially rebelled at this inhuman mission, special Gestapo forces took up the charge of herding their victims into woods, to ravines, or even against town walls where they would be shot en masse. The Japanese did the same in China, in Southeast Asia, and on the islands in the Pacific. The number of casualties in China alone has been estimated at thirty million, with untold millions murdered elsewhere.

On the eve of war in 1939, Hitler had predicted “the destruction of the Jewish race in Europe.” The Nazis’ initial plan for reducing the Jewish population included driving Jews into urban ghettos and making them live on minimal rations until they died of starvation or disease. There was also direct murder. Around Soviet towns, the Nazis killed ten thousand or more at a time, often with the help of local anti-Semitic volunteers. In Jedwabne, Poland, some eight hundred citizens on their own initiative beat and burned their Jewish neighbors to death and took their property—evidence that the Holocaust was not simply a Nazi initiative. However, the “Final Solution”—the Nazis’ plan to murder all of Europe’s Jews systematically—was not yet fully under way.

An organized, technological system for transporting Jews to extermination sites had taken shape by the fall of 1941 and was formalized at a meeting in Wannsee, Germany, in January 1942. Although Hitler did not attend the meeting at Wannsee, his responsibility for the Holocaust is clear: he discussed the Final Solution’s progress, issued oral directives for it, and had made violent anti-Semitism a basis for Nazism from the beginning. Scientists, doctors, lawyers, government workers, and Nazi officials took initiative in making the Holocaust work. Six camps in Poland were developed specifically for the purposes of mass murder (Map 26.3). Using techniques developed in the T4 project, which killed disabled and elderly people, the camp at Chelmno initially gassed Christian Poles and Soviet prisoners of war. Specially designed crematoria for the mass burning of corpses started functioning in 1943. By then, Auschwitz had the capacity to burn 1.7 million bodies per year. About 60 percent of new arrivals—particularly children, women, and old people—were selected for immediate murder in the gas chambers; the other 40 percent labored until, utterly used up, they too were gassed.

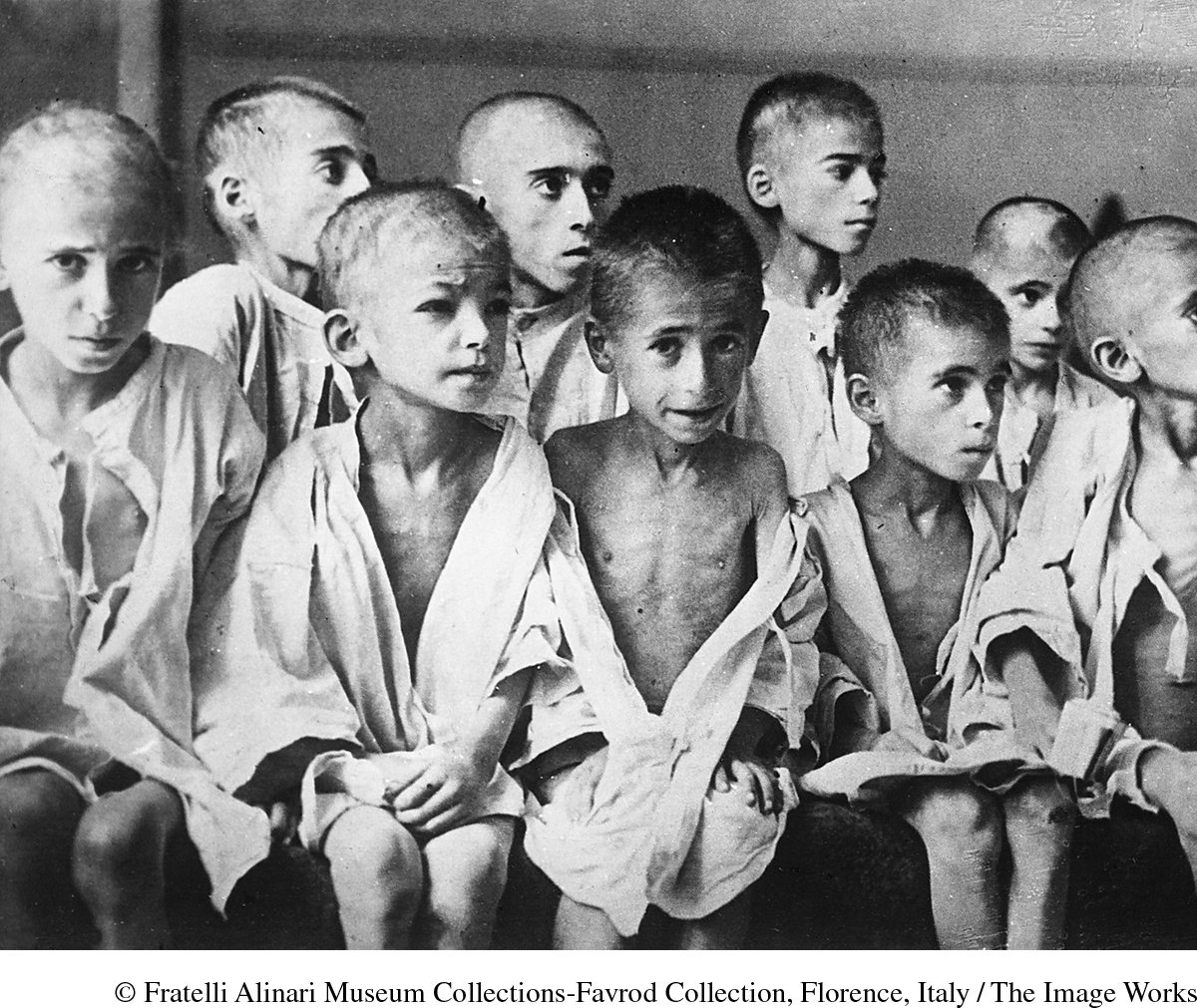

Victims from all over Europe were sent to extermination camps. In the ghettos of European cities, councils of Jewish leaders, such as the one in Amsterdam where Etty Hillesum worked, often chose those to be sent for “resettlement in the east”—a phrase used to mask the Nazis’ true plans. For weakened, poorly armed ghetto inhabitants, open resistance meant certain death. When Jews bravely rose up against their Nazi captors in Warsaw in 1943, they were mercilessly butchered. The Nazis also took pains to cloak the purpose of the extermination camps. Bands played to greet incoming trainloads of victims, and survivors later noted that the purpose of the camps was so unthinkable that potential victims could not begin to imagine their fate. Those not chosen for immediate murder had their heads shaved and were disinfected. So began life in “a living hell,” as one survivor wrote.

The camps were scenes of struggle for life in the face of torture and death. Overworked inmates usually received less than five hundred calories per day, far below the minimum needed to keep an adult in good health. As diseases swept through the camps, doctors performed unbelievably cruel medical experiments with no anesthesia on pregnant women, twins, and other innocent people in the name of advancing “racial science.” Despite the harsh conditions, however, some people maintained their spirit: prisoners forged new friendships, and women in particular observed religious holidays and celebrated birthdays. Thanks to those sharing a bread ration, wrote the Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi, “I managed not to forget that I myself was a man.” In the end, six million Jews, the vast majority from eastern Europe—along with an estimated five to six million Slavs, Sinti and Roma (often called Gypsies), homosexuals, and countless others—were deliberately murdered in the Nazi genocidal fury. This vast crime perpetrated by apparently civilized people still shocks and outrages the world.