Economic Disaster Strikes

Printed Page 860

Important EventsEconomic Disaster Strikes

In the 1920s, U.S. corporations and banks as well as millions of individual Americans had not only invested their money but also borrowed funds to make these investments in the soaring stock market. They used easy credit to buy shares in popular companies based on electric, automotive, and other new technologies. By the end of the decade, the Federal Reserve Bank—the nation’s central bank, which controlled financial policy—tried to slow speculation by limiting credit availability and causing brokers to demand that their clients immediately pay back the money they had borrowed to buy stock. As stocks were sold to raise the necessary cash, the market collapsed. Between early October and mid-November 1929, the value of businesses listed on the U.S. stock exchange dropped from $87 billion to $30 billion. For individuals and for the economy as a whole, it was the beginning of catastrophe.

The crash helped bring on a global depression that unfolded over the course of several years. The United States had financed the international economic growth of the previous five years, so when the suddenly strapped U.S. banks cut back on loans and called in debts, they undermined businesses at home and abroad. Jobs dwindled and a decline in consumer buying slowed the world economy, including the young businesses of eastern Europe.

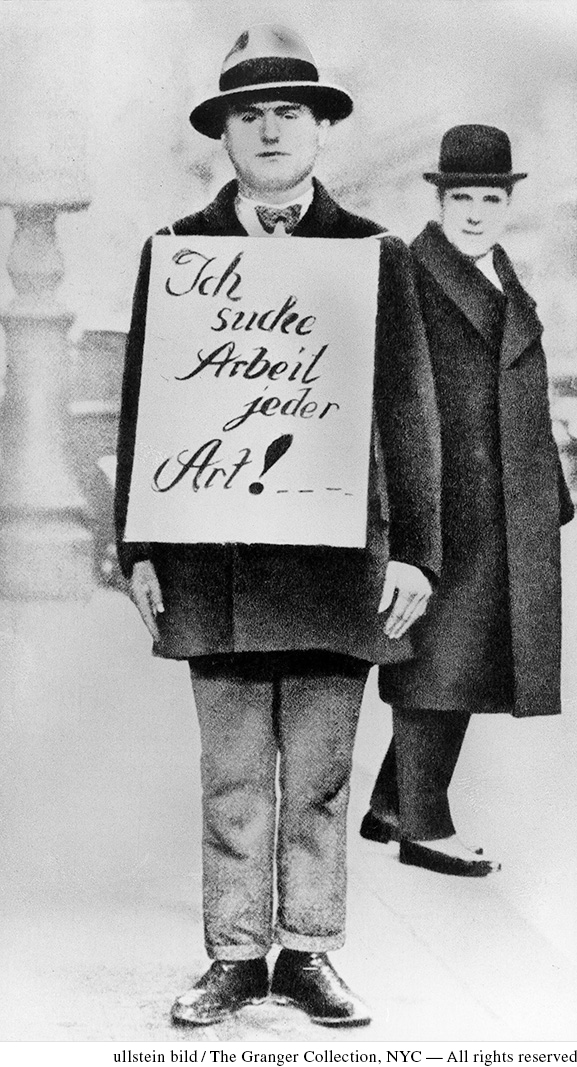

The Great Depression left no sector of the world economy unscathed, but government actions made the depression worse. To try to spur their economies, governments cut budgets and set high tariffs against foreign goods; these policies discouraged the consumer spending and international trade needed to spark the economy. Officials in charge of the flow of global money that fostered commerce desperately guarded their own supplies of gold. Unemployment soared: Great Britain—with its outdated textile, steel, and coal industries—had close to three million unemployed in 1932. By 1933, almost six million German workers, or about one-third of the workforce, had lost their jobs.

Agricultural prices had been declining for several years because of technological advances and abundant harvests around the world. With their incomes slashed, millions of small farmers had no money to buy the chemical fertilizers and motorized machinery they needed to remain competitive. Now creditors confiscated farms. Eastern and southern European peasants, who had pressed for the redistribution of land after World War I, could not afford to operate their newly acquired farms, and they, too, went under.