Origins of the Cold War

Printed Page 903

Important EventsOrigins of the Cold War

The cold war between the United States and the Soviet Union, which began in 1945, would afflict the world for more than four decades. No peace treaty officially ended World War II to document what went wrong, as in the Peace of Paris of 1919–1920. Therefore, the origins of the cold war remain a matter of debate, with historians faulting both sides for starting the dangerous rivalry. Some point to consistent U.S., British, and French hostility to the Soviets because of Communists’ abolition of private property and Russia’s withdrawal from World War I. Others stress Stalin’s aggressive policies, notably the 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact and Soviet expansionism.

Suspicion ran deep among the Allied leadership during the war: Stalin believed that Churchill and Roosevelt were deliberately letting the USSR bear the brunt of Hitler’s rampage across the continent as part of their anti-Communist policy. He rightly viewed Churchill in particular as interested primarily in preserving Britain’s imperial power, no matter what the cost in Soviet lives. At the time, some Americans believed that dropping the atomic bomb on Japan would also frighten the Soviets and discourage them from making any more land grabs. In addition, the new U.S. president, Harry Truman, cut off aid to the USSR almost the instant the last gun was fired, fueling Stalin’s suspicions and leading to the takeover of eastern Europe as a permanent “buffer zone” of dependent European states. Across the Atlantic, members of the U.S. State Department fueled U.S. fears by depicting Stalin as another in a long line of neurotic Asian tyrants thirsting for world domination.

The Cold War

| 1945–1949 | USSR establishes satellite states in eastern Europe |

| 1947 | Truman Doctrine announces American commitment to contain communism; Marshall Plan provides massive aid to rebuild Europe |

| 1948–1949 | Soviet troops blockade Berlin; United States airlifts provisions to Berliners |

| 1949 | West Germany and East Germany are formed; Western nations form North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO); Soviet bloc establishes Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON); USSR tests its first nuclear weapon |

| 1950–1953 | Korean War |

| 1950–1954 | U.S. senator Joseph McCarthy leads hunt for American Communists |

| 1953 | Stalin dies |

| 1955 | USSR and eastern-bloc countries form military alliance, the Warsaw Pact |

| 1956 | Khrushchev denounces Stalin in “secret speech” to Communist Party Congress; Hungarians revolt unsuccessfully against Soviet domination |

| 1959 | Fidel Castro comes to power in Cuba |

| 1961 | Berlin Wall is erected |

| 1962 | Cuban missile crisis |

The cold war thus became a series of moves and countermoves in the shared occupation of a rich European heartland that had fallen into chaos. In line with the view of its political needs, the USSR repressed democratic coalition governments of liberals, socialists, Communists, and peasant parties in central and eastern Europe between 1945 and 1949. It imposed Communist rule almost immediately in Bulgaria and Romania. In Romania, Stalin cited citizen violence in 1945 as the excuse to demand an ouster of all non-Communists from the civil service and cabinet. In Poland, the Communists fixed the election results of 1945 and 1946 to create the illusion of approval for communism.

The United States worried that Communist power would spread to western Europe. The Communists’ promises of better conditions appealed to hungry workers in Europe, while memories of Communist leadership in the resistance to fascism gave it powerful appeal. In March 1947, Truman reacted by announcing the Truman Doctrine—the use of economic and military aid to block communism. The president requested $400 million in military aid for Greece and Turkey, where the Communists were also exerting pressure. Fearing that Americans would balk at backing an undemocratic Greece, the U.S. Congress said it would agree to the program only if, as one congressman put it, Truman would “scare the hell out of the country.” Truman thus publicized the expensive aid program as a necessary first step to prevent Soviet conquest of the world. The show of American support made the Communists back off.

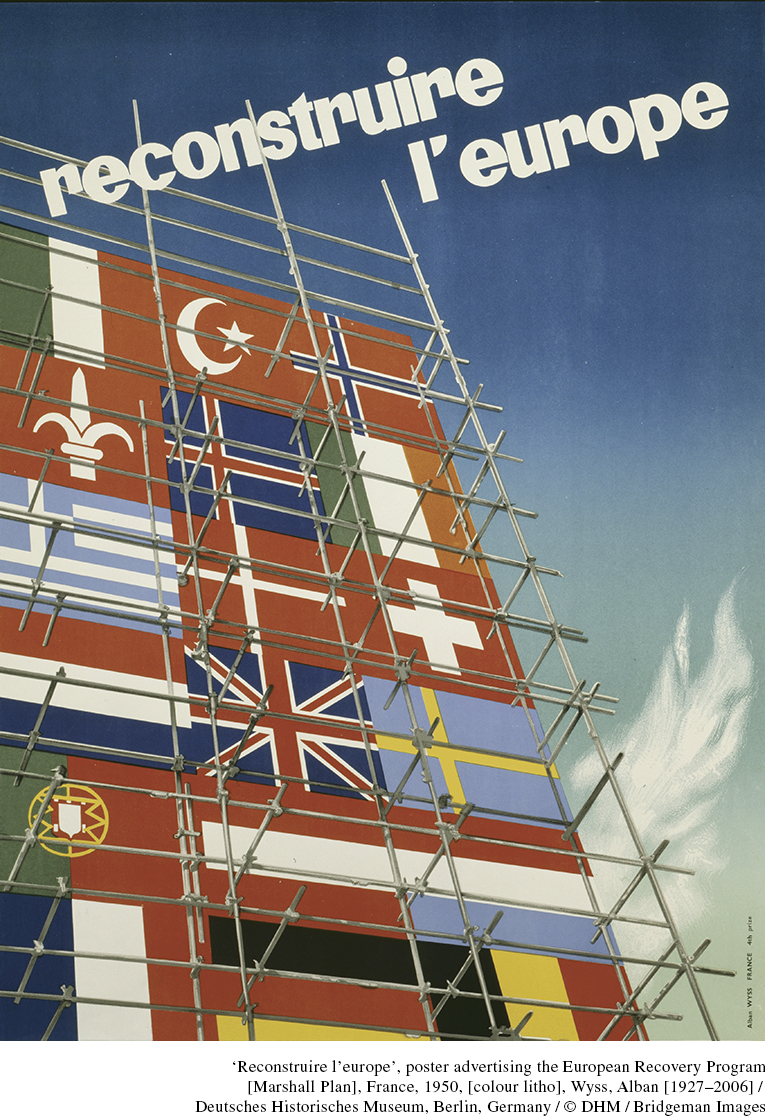

In 1947, the United States also devised the Marshall Plan—a program of massive economic aid to Europe—to relieve the daily hardships that were making communism attractive to Europeans. “The seeds of totalitarian regimes are nurtured by misery and want,” Truman warned. Named after Secretary of State George C. Marshall, who proposed the plan, the program’s direct aid would immediately improve everyday life, while its loans and financial credits would restart international trade. The government claimed that the Marshall Plan was not directed “against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos.” By the early 1950s, the United States had sent Europe more than $12 billion in food, equipment, and services, reducing communism’s appeal in the countries of western Europe that received the aid.

Stalin saw the Marshall Plan as a U.S. political trick because the devastated USSR had little aid to offer client countries in eastern and central Europe. He thus clamped down still harder on eastern European governments, preventing them from responding to the U.S. offer of assistance and eliminating the last scraps of democracy in Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. The populace accepted the change so passively that Communist leaders said the takeover was “like cutting butter with a knife.”

The only exception to the Soviet sweep in eastern Europe came in Yugoslavia, under the Communist ruler known as Tito (Josip Broz, 1892–1980). During the war, Tito had led the powerful anti-Nazi Yugoslav “partisans.” After the war, he drew on support from Serbs, Croats, and Muslims to mount a Communist revolution, but one explicitly meant to avoid Soviet influence. Eager for Yugoslavia to develop industrially rather than simply serve Soviet needs, Tito remarked, “We study and take as an example the Soviet system, but we are developing socialism in our country in somewhat different forms.” Stalin was furious; in his eyes, commitment to communism meant obedience to him. Nonetheless, Yugoslavia emerged from its Communist revolution as a culturally diverse federation of six republics and two independent provinces within Serbia that held together until Tito’s death in 1980.