Chapter 12. How Would You Know If Stress Increases Risk of Disease?

12.1

By:

C. Nathan DeWall, University of Kentucky

David G. Myers, Hope College

12.2

Note: You will be guided through the Intro, Design, Measure, Interpret, Conclusion, and Quiz sections of this activity. You can see your progress highlighted in the non-clickable, navigational list at the right.

Watch this video from your author, David Myers, for a helpful, very brief overview of the activity.

12.3

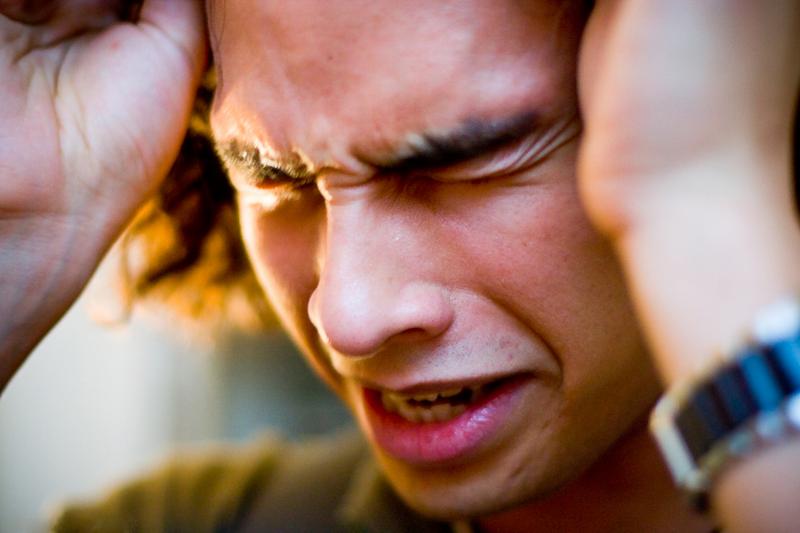

So, how would you know if stress increases risk of disease? To study this question effectively in your role as researcher, you need to DESIGN an appropriate study that will lead to meaningful results, MEASURE risk of contracting a specific type of disease, and INTERPRET the larger meaning of your results, considering how your findings would apply to the population as a whole. In this study, we will focus on whether stress increases risk of heart disease.

We will start by choosing a good research DESIGN. Of the options below, which one would be best to find out if stress increases risk of disease?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

Click on "Video Hint" below to see brief animations describing Naturalistic Observation, Longitudinal Studies, and Experiments.

Video Hint

12.4

Naturalistic Observation:

Longitudinal and Cross-Sectional Studies:

Experiments:

12.5

You have chosen a Naturalistic Observation design. Researchers generally use this design when they want to carefully observe a small group of participants and make notes about what they do. For example, those seeking to learn about the spread of the flu have spent many thousands of hours tracking how people physically interact with others and watching for meaningful patterns.

Of the following options, which one represents the best group for your study?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

12.6

What could we learn from these participant choices?

A small group of people who eat at restaurants every night. This option does not tell you about your participants’ weight or the size of the dinner plates they use. To know whether using larger dinner plates make us fat, you would need to study a group of individuals who have average body weight. This way you can determine whether changing the size of the plates they use causes them to behave in ways that will increase their weight.

A small group of people who are obese. This option tells you about your participants’ weight but not about the size of the dinner plates they use. To know whether using larger dinner plates makes us fat, you would need to study a group of individuals who have average body weight (not just people who are obese), and then vary the size of the dinner plates they use to see if that causes them to increase their weight.

A small group of people who are thin. This option tells you about your participants’ weight but not about the size of the dinner plates they use. To know whether using larger dinner plates makes us fat, you would need to study a group of individuals who have average body weight (not just people who are thin), and then vary the size of the dinner plates they use to see if that causes them to increase their weight.

A small group of people who have average body weight. You were right to choose people who have average body weight, but this option doesn’t tell us about the size of the dinner plates they use. To know whether using larger dinner plates makes us fat, you would need to study a group of individuals who have average body weight, and then vary the size of the dinner plates they use to see if that causes them to increase their weight. Also, you would need to study a large group, not a small group as in this Case Study approach, in order to determine whether the idea of using larger dinner plates making us fat may apply to the larger population.

Trying to choose a sample of participants helps us realize that NATURALISTIC OBSERVATION IS NOT THE BEST RESEARCH DESIGN to test this question. We’d get more helpful results by retesting the same people’s stress levels over a period of several years and correlating changes in stress levels with their risk for heart disease. This would help us determine whether stress increases risk of disease.

Click “Next” to go back and try again to select the most effective research design.

12.7

You have chosen an Experimental design, which means you want to systematically change one variable to determine whether it causes a change in another variable. For example, suppose a researcher wants to know whether giving a public speech increases levels of the stress hormone cortisol. The researcher would set up two groups. In the experimental group, people would give a public speech. In the control group, people would read about someone giving a public speech. Then the researcher would ask all participants to provide a saliva sample, which the researcher would use to measure levels of cortisol. This would allow the researcher to determine whether people who give a public speech, compared with those who read about giving a public speech, have higher cortisol levels. (They do. Giving a public speech typically stresses people out.)

Describe below how you would set up your experimental study to determine whether stress increases risk of disease:

12.8

It would be difficult to use an experimental design, because you cannot assign people to experience massive amounts of stress over many years. That wouldn’t be ethical. You would also have difficulty getting people to participate! We cannot say that stress causes heart disease. We need to determine whether stress is related to people experiencing more heart disease. For more on Research Ethics, and why we can’t always use an Experimental design in psychology research, click on “Video Hint” below.

Video Hint

So, EXPERIMENTAL IS NOT THE BEST RESEARCH DESIGN for this study.

Click “Next” to go back and try again to select the most effective research design.

12.9

Research Ethics:

12.10

Nice work! You have correctly chosen to use a Longitudinal Correlational Design for your study. This means you will retest stress levels and risk of heart disease in the same individuals over many years.

Next, you need to choose the most appropriate study participants.

Of the following options, which one represents the best group for your study?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

12.11

You chose A group of people who have heart disease, but this is NOT CORRECT.

This option does not allow you to test whether stress increases risk of heart disease, because you would have no way to compare with people who don’t have heart disease. To stress increases risk of disease, you would need to study individuals who vary in their levels of disease.

Click “Next” to try again to choose the most appropriate study participants.

12.12

You chose A group of people who report having almost no stress in their lives, but this is NOT CORRECT.

It would be difficult to examine the relationship between stress and risk of disease among people who experience little or no stress. To know whether stress increases risk of disease, you would need to study individuals who experience different levels of stress.

Click “Next” to try again to choose the most appropriate study participants.

12.13

You chose A group of people who are stress-prone and hot-tempered, but this is NOT CORRECT.

It would be difficult to examine the relationship between stress and risk of disease among only people who experience a lot of stress. You would have no way to compare with people who don’t experience a lot of stress. To know whether stress increases risk of disease, you would need to study individuals who experience varying levels of stress.

Click “Next” to try again to choose the most appropriate study participants.

12.14

Good job! You have correctly chosen to use a Longitudinal Correlational Design, in which you will retest stress levels and risk of heart disease in the same individuals over many years. You also chose an appropriate sample of participants—A group that includes people who are stress-prone and also people who are relaxed and mellow. Now you need to determine how best to MEASURE the relevant behavior or mental process, which in this case is the risk of heart disease.

12.15

Of the following options, which one represents the best way to measure risk of heart disease?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

12.16

You chose Have participants report whether any member of their family has experienced heart disease, but this is NOT CORRECT.

Knowing whether participants have a family history of heart disease is important, but it does not tell you anything about participants’ actual heart disease. To know whether stress increases risk of disease, we have to measure participants’ actual heart disease.

Click “Next” to try again to select the best way to measure whether stress increases risk of disease.

12.17

You chose Have participants report whether they think they currently have heart disease, but this is NOT CORRECT.

This option would not give you direct information about participants’ health. It would only tell you if participants thought they had heart disease. Some healthy people always think they are sick, and some unhealthy people think they are well. To know whether stress increases risk of disease, we have to measure participants’ actual heart disease.

Click “Next” to try again to select the best way to measure whether stress increases risk of disease.

12.18

You chose Have participants report whether they engage in behaviors known to reduce the likelihood of heart disease, such as healthy eating and a regular exercise routine, but this is NOT CORRECT.

By choosing this option, you did not measure actual heart disease. Instead, you asked participants to report whether they do things that might reduce their risk of heart disease. To know whether stress increases risk of disease, we have to measure participants’ actual heart disease.

Click “Next” to try again to select the best way to measure whether stress increases risk of disease.

12.19

![photo of a smiling, male, nonwhite medical doctor holding a clipboard or some charts/folders.]](asset/chapter_12/myers11e_12.16_91498242.jpg)

Nice job! You have correctly chosen to use a Longitudinal Correlational design, in which you will retest stress and heart disease levels in the same individuals over many years. You chose an appropriate sample of participants—a group of people who experience varying levels of stress. You also chose how best to MEASURE the relevant behavior or mental process, which in this case is heart disease. You selected the option, Have participants provide their complete medical history, which will include objective measures of heart disease.

In one famous study, actual researchers compared stress-prone, negative, hot-tempered, Type A, middle-aged men with their more relaxed and mellow Type B counterparts (Rosenman et al., 1976). Nine years later, 257 of the original 3,000 participants had suffered heart attacks. Guess what percentage of the heart attack sufferers were severely stressed-out Type A individuals? Sixty-nine percent! Additional studies have supported the link between living with great stress and increased risk of heart disease and heart attacks (Allesøe et al., 2010; Slopen et al., 2010). So, stress does in fact increase risk of heart disease.

Now you need to consider how you can apply what you’ve learned to the larger population—beyond the people you’ve studied. Consider where you might encounter roadblocks to confidence in your results. What factors might keep you from being able to apply what you’ve learned in a broader context?

12.20

You tested whether stress increases the risk of disease by regularly measuring stress levels and also objective indicators of heart disease. Several factors could affect the risk of heart disease, and they might not have any relation to stress levels. Just think of the many relaxed and mellow people each year who suffer heart attacks! Factors that could interfere with your INTERPRETATION of results are called confounding variables.

From the factors listed below, select those that could affect your confidence about whether stress increases risk of disease:

| Whether participants have a healthy diet and a regular exercise routine | |

| How much participants agree with the finding that stress increases risk of disease | |

| Whether participants believe that other people are more likely than themselves to experience heart disease | |

| Whether participants have a family history of heart disease | |

| Participants’ occupation type (e.g., stockbroker, meditation instructor) |

Click on "Video Hint" below to see a brief animation describing Confounding Variables.

Video Hint

12.21

Confounding Variables:

12.22

The confounding variables for your study would include those highlighted below:

| Whether participants have a healthy diet and a regular exercise routine | |

| How much participants agree with the finding that stress increases risk of disease | |

| Whether participants believe that other people are more likely than themselves to experience heart disease | |

| Whether participants have a family history of heart disease | |

| Participants’ occupation type (e.g., stockbroker, meditation instructor) |

You are trying to predict risk of heart disease. Numerous factors can increase or decrease one’s risk of heart disease, including diet, exercise, and family history. To have confidence in your results, you need to account for these factors that influence the risk of heart disease. This way, you can be more confident that any changes in heart disease you observe relate to your participants’ stress levels.

It is also important to keep track of your participants’ occupation. Your study is about whether stress, not merely occupation, increases risk of disease. Some professions involve more stress than others. To make sure your results are due to stress and not occupation, you need to take into account the type of work your participants pursue.

Unless you keep track of the highlighted confounding variables, you might draw incorrect conclusions about your study results.

12.23

You may do better on the Quiz if you take notes while watching this video. Feel free to pause the video or re-watch it as often as you like.

REFERENCES

Allesøe, K., Hundrup, V. A., Thomsen, J. F., & Osler, M. (2010). Psychosocial work environment and risk of ischaemic heart disease in women: The Danish Nurse Cohort Study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 67, 318–322.

Chida, Y., & Vedhara, K. (2009). Adverse psychosocial factors predict poorer prognosis in HIV disease: A meta-analytic review of prospective investigations. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 23, 434–445.

Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R. H. (1974). Type A behavior and your heart. Fawcett.

Rosenman, R. H., Brand, R. J., Sholtz, R. I.,& Friedman, M. (1976). Multivariate prediction of coronary heart disease during 8.5 year follow-up in the Western Collaborative Group Study. The American Journal of Cardiology, 37, 903-910.

Slopen, N., Glynn, R. J., Buring, J., & Albert, M. A. (2010, November 23). Job strain, job insecurity, and incident cardiovascular disease in the Women’s Health Study (Abstract 18520). Circulation, A18520 (circ.ahajournals.org).

12.24

QUIZ: NOW WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

1. According to the results of your study, what increases with greater stress?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

2. Which of the following statements is FALSE, based on what you learned from this activity?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

3. You chose to account for whether study participants had a healthy diet and a regular exercise routine. These factors that can reduce confidence in your results are known as:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

4. Based on what you learned from this activity, choosing to work at a stressful job ________ the risk of experiencing ________.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

5. If someone asks you whether stress increases the risk of disease, how might you respond based on what you learned in this activity?